Flea Tapeworm Life Cycle (Dipylidium caninum).

Flea tapeworms (

Dipylidium caninum species) are a common species of tapeworm infesting dogs and cats and occasionally humans. Particularly common in puppies and kittens, flea tape worms can make for an unpleasant parasitic encounter for pet owners when they are discovered in the droppings of pets or found crawling out from the anuses of infested animals.

These rather-common cestode parasites pose a variety of problems for pets and pet owners including:

- non-specific intestinal disturbances - tapeworms can produce some non-specific signs of

intestinal discomfort and pain (e.g. colic signs) in animals and humans. Tapeworm afflicted humans often complain of cramping and nausea: signs that are generally difficult to ascribe to animals, but which probably do occur in them also (animals can't actually describe such vague feelings of cramping or nausea to us humans - so we are generally unaware of these signs in them).

- non-specific appetite changes - tapeworms can cause some animals

to go off their food or to become fussy or picky about their eating habits (this appetite loss is possibly the result of such factors as abdominal pain and nausea - described above). In contrast, certain other animals

develop a ravenous appetite in the face of tapeworm infestation because they are competing with

the parasite/s for nutrients (they need to physically eat more to provide enough nutrition for both themselves and the worms).

- body weakness, headaches, dizziness and delirium - described in human tapeworm infestations, non-specific signs of weakness, headache and dizziness may occur in animals also. Whether we would ever actually be likely to diagnose these sorts of non-specific signs in our pets is the real question, however - if our pets

can not actually describe sensations of dizziness or headache to us humans, then how would we ever know?

- malnutrition - very large numbers of flea tapeworms present in the intestinal tracts of dogs and cats (particularly small puppies and kittens) can result in the malabsorption of nutrients (food) by the infested animal. This can cause the tapeworm-parasitised animal to not receive the nutrition it needs (i.e. to not absorb its food properly), resulting in malnourishment, weight loss, ill-thrift and poor growth.

- poor coat quality - severe malnutrition and malabsorption of vitamins, minerals and proteins can result in reduced quality of the haircoat - e.g. brittleness, thinning, coarseness and loss of lustre of the coat.

- intestinal irritation and diarrhea - when an adult flea tapeworm inhabits the small intestine of an animal, it finds a suitable site along the lining of the intestinal lumen and grasps on to it using suckers and a spiny anchor-like organ called a rostellum. This spiky tapeworm grip is irritating to the wall of the intestine, creating discomfort for the animal host and alterations in intestinal motility

and regional intestinal mucus secretions, which can result in diarrhea (note that diarrhoea is mainly seen only in very heavy tapeworm infestations). In some individuals, the penetrating rostellum causes a severe inflammatory, allergic reaction within the host's intestine (the host's immune system actively rejects and attacks the tapeworm proteins), causing the animal host to exhibit abdominal pain and diarrhea.

- intestinal blockage - it is possible for massive tapeworm infestations to block up

the intestines of animals (especially small puppies and kittens), producing signs of intestinal obstruction

(e.g. vomiting, shock and even death). This is not common, but it can occur if worm burdens are large and/or if

someone deworms the infested animal, killing all of the worms in one hit (the tapeworms all die and let go of their intestinal attachments at the same time, resulting in a vast mass of deceased tapeworms flowing down the intestinal tract all at once and causing blockage).

- perineal or anal irritation and scooting - the migration of tapeworm segments from the anuses of infested dogs and cats can result in itching and irritation of the anus. The dog or cat

will respond by excessively licking the anus in order to remove the irritation or, if it can not reach, it will drag and rub its bottom on the ground to remove the irritation. This bottom rubbing, called "scooting", is usually a sign of anal or perineal irritation and evacuating tapeworms can be one cause of this (side note - anal gland impaction or infection is a much more common cause of scooting, however, it can be a sign seen in 'wormy' animals).

- fleas or lice - flea tapeworm infestation is usually associated with flea or lice infestations of the coat (see flea tapeworm life cycle diagram below). The finding of adult flea tapeworms or at least their proglottid segments (egg sacs) in the feces of animals is a strong indication that the animal in question is most likely parasitised by fleas or lice and is therefore also suffering from the problems (e.g. skin itching) associated with parasitism by these insect pests.

- annoyance - most pet owners don't like to see or hear their pets fastidiously licking their bottoms or rubbing their butts along the carpet. This annoyance is compounded when the rubbing activities result in fecal staining of floors or if tapeworm segments are actually seen extruding

from the animal's anus;

- gross-out factor - the sight of long tapeworms in the feces and/or white,

grub-like tapeworm segments crawling from a pet's anus is revolting and off-putting to many people who see such infestations as a sign of 'dirtiness' and 'disease' (even though clean pets can and do get flea tapeworms of course).

- zoonosis (human infestation) - Dipylidium caninum tapeworms can infest humans (generally children) who inadvertently ingest tapeworm-carrying fleas or lice (flea tapeworms are not transmitted directly to humans by their pets).

Of all of the problems mentioned above, the disgust factor (gross-out factor) is probably the most

significant and commonly seen in the vet clinic. Tapeworm-associated problems like malnutrition, intestinal irritation, perineal irritation, diarrhea, intestinal blockage and poor coat quality are seen of course and are greatly problematic for the host animal when they do occur, however, it must be stated that it generally

requires a massive tapeworm burden to be present before such severe signs are likely to be encountered

in practice. As a vet in Australia, I have not personally seen a flea tapeworm burden so massive as to result in a major malabsorption or intestinal disturbance issue (although under certain hygiene and living conditions, I do not doubt that it probably occurs). Far more commonly, people come to me in a panic because they have just found a large, white worm in the droppings of their cat or dog or seen a pale, fat, maggot-looking tapeworm segment slither out of the anus of their puppy. In these quite common situations, the animal in question is generally healthy and fine (it just needs worming treatment) - it's the owner who's the one needing the reassurance (and the smelling salts)!

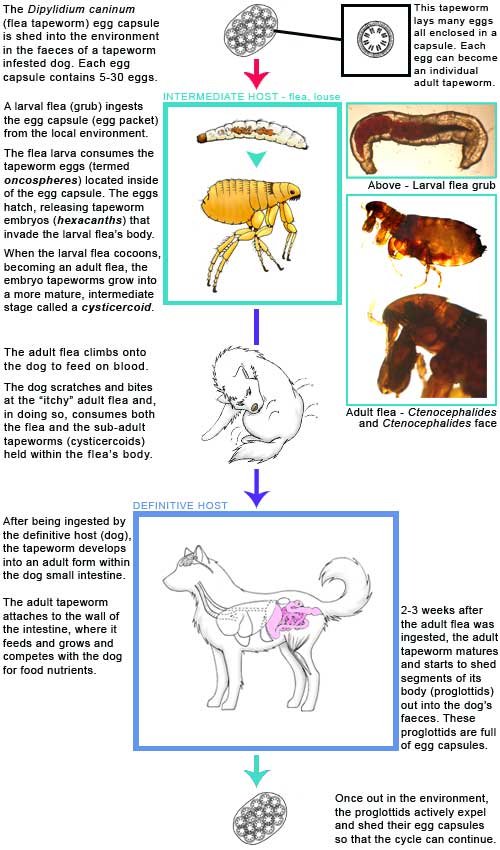

This flea tapeworm life cycle page contains a detailed, but simple-to-understand explanation of the

complete flea tapeworm life cycle. It comes complete with a full tapeworm life cycle diagram for ease of understanding. Explanation of the cycle is included, along with advice on how the flea tapeworm life cycle can be used as an aid in the control and treatment and prevention of flea tapeworms.

The Flea Tapeworm Life Cycle - Contents:

1) The flea tapeworm life cycle diagram - a complete step-by-step diagram of host animal flea tapeworm

infestation and its transmission via intermediate flea and louse hosts.

2) Treatment and prevention of flea tapeworm infestations.

1) The Flea Tapeworm Life Cycle Diagram:

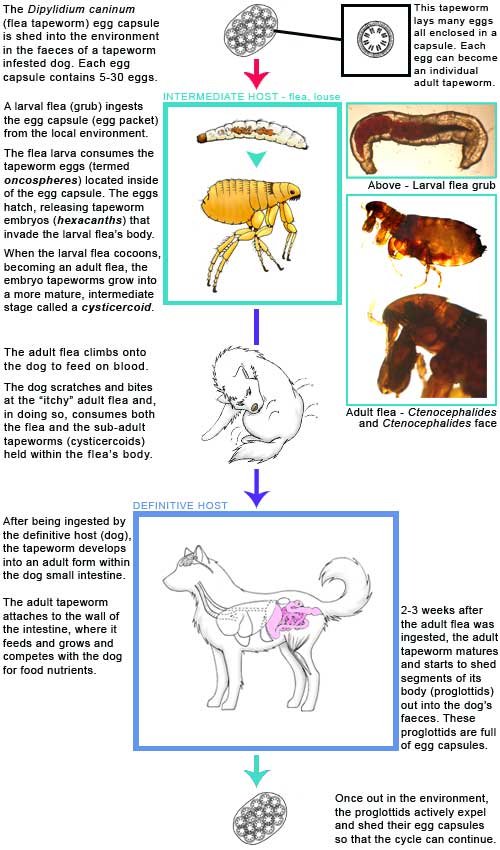

Flea tapeworm life cycle diagram: This is a diagram of the life cycle of a flea tapeworm (Dipylidium caninum).

The diagram shows the complete cycle of a flea tapeworm's existence - from egg to adult tapeworm to egg again (with the next generation of tapeworm eggs) - within the bodies of two very different, yet both equally essential, host animal species:

1. the intermediate host insect (flea or chewing louse) and

2. the definitive

host carnivore (dog, cat or man).

Adult flea tapeworms live and feed in the small intestine of such host animals as the dog (pictured in diagram),

cat and, occasionally, the human. These carnivorous host animals are termed definitive hosts with regard to the

tapeworm life cycle because they are the hosts that the parasitic tapeworm was intended for and that the tapeworm organism reaches adulthood and sexual maturity in.

The body of an adult tapeworm is made up of hundreds of individual segments, termed proglottids. These segments progress in size and maturity as you travel down the tapeworm's body: ranging from very tiny (those proglottids nearest the 'scolex' or head of the tapeworm) right through to very large (large, mature proglottid segments of the common flea tapeworm are generally described as being cigar-like in shape and about the size of a 'cucumber seed' in most texts).

Every individual tapeworm segment is essentially an individual egg-producing reproductive factory. Tapeworms are hermaphrodites (bearing both male and female sex structures). Each proglottid segment has its own

testicular-type organ structure/s and its own uterine organ structure/s (for creating and maturing eggs)

and every single proglottid is, therefore, capable of producing and fertilising its own set of eggs, once mature. The small-sized proglottids nearest the anchoring 'head' of the flea tapeworm are the most under-developed and immature of all the tapeworm's segments and are, consequently, incapable of creating fertile eggs because of their under-developed state. The large proglottids nearest the 'tail-end' of the tapeworm are the most mature of all the tapeworm's segments and are capable of having their eggs fertilized and matured into an embryo-bearing state.

Every individual tapeworm segment is essentially an individual egg-producing reproductive factory. Tapeworms are hermaphrodites (bearing both male and female sex structures). Each proglottid segment has its own

testicular-type organ structure/s and its own uterine organ structure/s (for creating and maturing eggs)

and every single proglottid is, therefore, capable of producing and fertilising its own set of eggs, once mature. The small-sized proglottids nearest the anchoring 'head' of the flea tapeworm are the most under-developed and immature of all the tapeworm's segments and are, consequently, incapable of creating fertile eggs because of their under-developed state. The large proglottids nearest the 'tail-end' of the tapeworm are the most mature of all the tapeworm's segments and are capable of having their eggs fertilized and matured into an embryo-bearing state.

Author's note: because each individual proglottid segment can reproduce sexually on its own, some texts have described

tapeworms as being almost like a colony (a large 'super-organism' made up of many individuals: each capable

of living and reproducing without much assistance from the whole). Unlike a true colony, however, the individual reproductive segments of a tapeworm can not exist quite so independently as individual units within the whole

organism. The individual tapeworm segments all rely on the survival of the tapeworm's head if they are to remain within the definitive host animal and survive and, also, there is but one nervous system (under the control of the tapeworm head) linking all of the proglottids together in the tapeworm chain (i.e. the individual proglottid reproductive units are not so independent that they have been given their own individual nervous systems and brains).

Author's note: Because every individual proglottid contains both male and female sex organs, it is theoretically possible for a single proglottid to 'self-fertilise' (self-inseminate its own eggs). In reality, however, it is probably much more common for individual proglottids to 'cross-fertilise' -

inseminating other, nearby proglottids on the same tapeworm 'chain' and/or even proglottids on completely separate

tapeworms (i.e. other flea tapeworms that just happen to be living within reach). This makes for a

better spread of tapeworm genes and lessens the degree of in-breeding.

When a proglottid enlarges and develops to a certain stage, becoming sexually mature, gametes (essentially sperm) from the male testicular components of the proglottid

segment fertilize the eggs (female) present within that or a nearby proglottid segment (as mentioned before, there can be cross-fertilisation from proglottid to proglottid). The newly fertilised tapeworm eggs mature

inside of the proglottid, developing embryos inside of them, and the proglottid continues to grow in size. A proglottid that contains fertilized eggs inside is said to be "gravid" (i.e. a gravid proglottid).

When a proglottid enlarges and develops to a certain stage, becoming sexually mature, gametes (essentially sperm) from the male testicular components of the proglottid

segment fertilize the eggs (female) present within that or a nearby proglottid segment (as mentioned before, there can be cross-fertilisation from proglottid to proglottid). The newly fertilised tapeworm eggs mature

inside of the proglottid, developing embryos inside of them, and the proglottid continues to grow in size. A proglottid that contains fertilized eggs inside is said to be "gravid" (i.e. a gravid proglottid).

Once the fertilised proglottid eggs are fully-matured (ready to enter the next stage of the tapeworm life cycle), the now-cucumber-seed-sized proglottid segment bearing them breaks away from the main body of the tapeworm.

This proglottid segment exits the definitive host animal's body via the anus. The segment either physically

crawls from the anus of the host animal by contracting its muscles and creeping along (people spotting these crawling

proglottid segments often think that their pet is infested with fly maggots) or it is voided in the animal's stools as the pet defecates.

Once out in the environment, the shed proglottid segment continues to writhe, breaking apart and expelling its fertilized, matured tapeworm eggs into the environment as it does so. The eggs of the flea tapeworm (Dipylidium species) are expelled from the proglottid segment in clustered groups

that are termed "packets" (packets - clusters of tapeworm eggs surrounded by a common membrane). Each egg 'packet'

contains up to around 30 individual tapeworm eggs (called oncospheres), each of which

contains an embryo (called a hexacanth) that has the potential to develop into an adult tapeworm at some point in the future (all going to plan with regard to the flea tapeworm life cycle, of course).

An intermediate host insect (usually a flea larva, but sometimes a biting louse) consumes the tapeworm egg packets present in the environment. Normally, flea larvae survive

on a diet of flea excreta (flea dirt) and environmental dander, but they will happily consume

tasty tapeworm eggs if they come across them! When the intermediate host consumes the tapeworm egg packet, the tapeworm embryos survive and hatch from their eggs inside of the body of

the intermediate host. Here the embryos develop further into an intermediate tapeworm stage called a cysticercoid. The cysticercoid stage of the flea tapeworm life cycle is able to survive the pupal stage

of the flea life cycle (when the flea transforms from flea larva into an adult flea by way of a cocoon).

Cysticercoids appearing inside of adult fleas and lice are infectious to the definitive host animal.

An intermediate host insect (usually a flea larva, but sometimes a biting louse) consumes the tapeworm egg packets present in the environment. Normally, flea larvae survive

on a diet of flea excreta (flea dirt) and environmental dander, but they will happily consume

tasty tapeworm eggs if they come across them! When the intermediate host consumes the tapeworm egg packet, the tapeworm embryos survive and hatch from their eggs inside of the body of

the intermediate host. Here the embryos develop further into an intermediate tapeworm stage called a cysticercoid. The cysticercoid stage of the flea tapeworm life cycle is able to survive the pupal stage

of the flea life cycle (when the flea transforms from flea larva into an adult flea by way of a cocoon).

Cysticercoids appearing inside of adult fleas and lice are infectious to the definitive host animal.

Author's note: an intermediate host animal (e.g. flea or louse insect in this case) is a host

animal that the tapeworm parasite needs to infest if it is to be able to complete part of its lifecycle. In this case, the flea tapeworm needs to infest an insect host if it is to hatch from the tapeworm

egg and transform from an embryonic (hexacanth) stage to an intermediate (cysticercoid) stage. The parasitic tape worm is unable to reach adulthood and sexual maturity inside of an intermediate host animal and needs to later enter the body of a definitive host animal like a dog or cat in order

to achieve sexual and reproductive maturity.

Author's note: an intermediate host animal (e.g. flea or louse insect in this case) is a host

animal that the tapeworm parasite needs to infest if it is to be able to complete part of its lifecycle. In this case, the flea tapeworm needs to infest an insect host if it is to hatch from the tapeworm

egg and transform from an embryonic (hexacanth) stage to an intermediate (cysticercoid) stage. The parasitic tape worm is unable to reach adulthood and sexual maturity inside of an intermediate host animal and needs to later enter the body of a definitive host animal like a dog or cat in order

to achieve sexual and reproductive maturity.

The definitive host animal ingests the cysticercoid stage of the flea tapeworm life cycle by consuming a louse or flea that has become infested with cysticercoids. Such consumption

of fleas and lice is more common that you would think. I come across quite a few dead fleas

when I perform fecal floats on animals, so it is true that infested dogs and cats do consume them. The fleas and lice are most likely consumed when itchy flea- and lice-infested animals

over-groom and chew their skin in an attempt to rid themselves of the skin irritation posed

by the insect pests.

When the definitive host animal consumes the tapeworm-infested insect host, the cysticercoid

stage of the tapeworm comes out of the ingested insect's body and enters the intestinal tract of the

definitive host. Here it develops into a final-stage adult tapeworm, attaches to the wall

of the animal's intestinal tract and starts budding off a chain of proglottid segments. The first fully-mature, egg-bearing proglottid segments start breaking away from the adult tapeworm's

body and appearing in the animal's environment about 2-3 weeks after the cysticercoid-infested

insect was first ingested.

Thus the flea tapeworm life cycle continues ...

2) Treatment and prevention of flea tapeworm infestations.

Adult flea tapeworms in dogs and cats can be eliminated from the animal's intestines

using tapeworm-specific anti-cestodal medications such as praziquantel or niclosamide (of the

two drugs, praziquantel is the anticestodal drug most commonly included in commercially-available

dog and cat 'all-wormers'). Basic information on niclosamide and praziquantel is contained below.

When an adequate dose of either anti-tapeworm drug is administered to the definitive host animal, the tapeworms die and are voided in the host animal's feces (pet owners may find several large, dead tapeworms

in their animal's feces following the administration of just such a wormer). This single treatment is usually curative, however, several doses may be needed to completely rid an animal of a very large tapeworm

burden (if a large tapeworm burden is suspected, the praziquantel can be repeated two-weekly for a couple of doses

to be sure of getting them all).

Author's note: Be aware that most deworming medications (aside from some heartworm meds) do not generally last very long in a treated-animal's system. When an all-wormer is given to a pet, the drugs work rapidly, killing off the adult worm parasites, before disappearing. The drugs do not hang around to protect the pet against subsequent worm infestations. This means that should

the pet continue to eat cysticercoid-infested fleas and lice in the days following

the deworming treatment, they will most likely become rapidly re-infested with adult tapeworms.

Following the ingestion of a cysticercoid-infested intermediate host flea or louse, a definitive host

dog or cat can have a reproductively-mature, proglottid-shedding adult tapeworm inside of its

intestine within a mere 2-3 weeks. In heavy flea or lice infestations, this could mean that a pet owner might need to repeat worm (tapeworm-treat) his dog or cat every 2-3 weeks to keep the adult tapeworm numbers under control!

Because 2-3 weekly worming is generally not very practical for most pet owners (particularly owners

of hard-to-pill cats) and could lead to toxicity concerns with the anticestodal drugs

being given so often, the best option for the ongoing control of flea tapeworms is to:

a) give the animal regular tapeworming medications (as per the manufacturer's directions) and

b) control the flea and lice populations that cause the dog or cat to catch the tapeworms (see why

it is so useful to understand the tapeworm life cycle?).

Both hosts need to be targeted if flea tapeworms are to be properly controlled and eradicated

in a household. It is no good simply treating the tapeworms in the definitive host's intestines if the environment

and pet-fur is full of infested intermediate host fleas or lice that will rapidly reinfest the pet with tapeworms!

For info on flea control and breaking the flea lifecycle, click here.

For info on the lice life cycle and lice treatment options, click here. Note that lice infestations in cats and

dogs are generally treated with spot-on treatments like Frontline.

Praziquantel.

Praziquantel is a powerful tapeworm-killing drug that is generally included in the vast majority

of commercially-available 'all-wormers' given to dogs and cats. It has a high margin of safety in dogs and cats

(and many other species) and exhibits very good activity against most of the major tapeworm species affecting our domestic pets (including: the common flea tapeworm - Dipylidium caninum; the hydatid

tapeworms - Echinococcus granulosus and E. multilocularis; the zipper worm - Spirometra

and the many varities of Taenia tapeworm species). It is because of this excellent activity against such a wide range of pet tapeworm parasites that praziquantel tends to be favoured over

niclosamide in the control of tapeworms in domestic household animals.

How it works:

Tapeworms are coated in protein molecules that shield them from being recognised and attacked by

the host animal's immune system. These protein molecules turn over and shed from the tapeworm's body surface

constantly. By the time the host's immune system recognises and starts to attack one lot of tapeworm surface molecules, these have been shed from the tapeworm's 'skin', leaving the immune system with nothing recognisable to attack.

Praziquantel works by disrupting the surface integument of the worm such that the animal's immune system is capable of recognizing the tape worm as foreign and actively attacking it. Additionally, praziquantel

also works by massively increasing the influx of calcium ions into the tapeworm's body. This calcium overload causes

the worm's muscles to become over-stimulated such that the worm develops stiffness and rigidity. The rigid

tapeworm is unable to maintain its hold on the host's gut wall and is, consequently, voided from the animal's intestinal tract via the faeces.

Features of praziquantel:

- The treatment of choice for tapeworms in dogs and cats.

- Kills a wide range of cestode (tapeworm) species in people and animals.

- Kills Schistosoma - an important parasite of humans, which causes a terrible, often fatal, liver condition called bilharzia (common in third world countries).

- Also kills some forms of trematode (fluke) parasite in livestock animals.

- In very high doses, praziquantel also kills certain intermediate-stage, larval tapeworm forms. Unfortunately

for us humans, praziquantel does not kill hydatid tapeworm cysts.

- Very effective at killing adult Dipylidium caninum flea tapeworms and also many other important tapeworm types afflicting domestic animals (hydatid tapeworms being the most serious).

- A dose of 2.5-5mg/kg is needed to kill Dipylidium. Most all-wormers contain 5mg/kg praziquantel, which is ample for killing this flea tapeworm.

- A dose of 5-10mg/kg is needed to kill hydatid tapeworms (Echinococcus species) in dogs. The higher

dose range is recommended to kill juvenile forms of the worms in dogs. Most all-wormers contain 5mg/kg praziquantel, which is within the dose range for killing these nasty tapeworms, however, given how dangerous hydatid tapeworm infestations are to people, if I was a dog owner living in a high hydatid risk situation, I would probably err on the side of caution and give the higher dose (10mg/kg). For info on hydatid tapeworms, see our hydatid tapeworm page.

- Some tapeworms like Spirometra and Diphyllobothrium erinacei require an intermediate dose range (7.5mg/kg) be given on 2 consecutive days.

- Many of the tapeworms and flukes afflicting livestock animals need high doses of praziquantel if they are to be cleared (in the order of 15-30mg/kg and higher).

- Praziquantel, given orally, absorbs into the animal's body rapidly, reaching many organs including the liver and brain (this systemic absorption is why praziquantel is effective against Schistosoma and certain larval tapeworm forms).

- Praziquantel has a wide safety margin and is difficult to overdose (dogs were tested on up to 180mg/kg orally with little side effect).

- Praziquantel is thought to be safe in pregnant and breeding animals (check with your vet).

- Some praziquantel-containing products advise not using praziquantel in puppies or kittens under 4 weeks of age.

Author's note: A related product called epsiprantel has been used to kill flea tapeworms

in dogs and cats. I have never used the product personally and can not vouch for its efficacy.

NOTE - Please read our disclaimer before attempting to self-diagnose and dose your animals with

any drugs mentioned on these pages. Pet Informed is a general advice website only and mistakes can be

made - we always recommend that you double-check any of our information with your own vet.

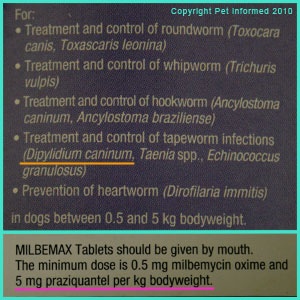

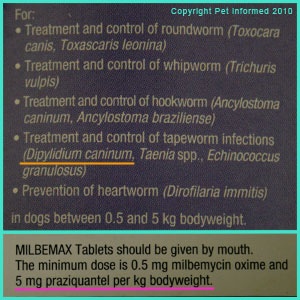

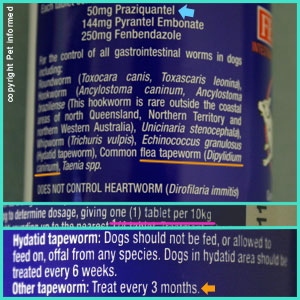

Flea tapeworm life cycle picture: These are photographs of the box-labels of a common dog and cat

all-wormer called Milbemax. You can see from the first image that the product contains praziquantel

(25mg of praziquantel per tablet - underlined in aqua). The second image shows the range of parasites that

the product kills. The flea tapeworm, Dipylidium caninum (underlined in orange) is listed

as one of the parasites that this product kills. Also mentioned on the Milbemax box was the minimum recommended dose rate of praziquantel (underlined in pink) - it is listed as 5mg/kg.

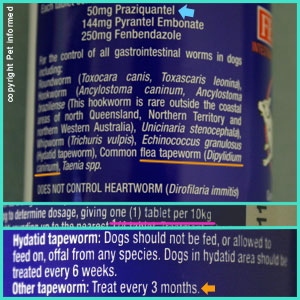

Flea tapeworm life cycle picture: These are photographs of the bottle-labels of a common dog and cat

all-wormer called Fenpral. The first image is a picture of the product bottle (dog version of Fenpral). The second image shows that the product contains 50mg of praziquantel per tablet (blue arrow). The image shows the range of parasites that

the product kills. The flea tapeworm, Dipylidium caninum (underlined in orange) is listed

as one of the parasites that this product kills. Also mentioned on the Fenpral bottle is the minimum recommended dose rate of praziquantel (underlined in pink) - it is listed as being 1 tablet per 10kg of

bodyweight. Given that a single tablet contains 50mg of praziquantel, this must mean that the

minimum dose rate for praziquantel is, again, 5mg/kg (i.e. a 10kg dog gets 50mg so a 1kg dog must get 5mg).

Niclosamide.

Niclosamide is a tapeworm-killing drug that has been used in the past for killing tapeworm

infestations in domestic animals and people. In the animal field, niclosamide is used most commonly to

treat tapeworm infestations in livestock and, although it can be used in dogs and cats, it generally

has not taken off in these species because it has little effect on hydatid tapeworms and only a limited effect (not reliable) on flea tapeworms. For dog and cat tapeworms, praziquantel

is considered to be superior. On the plus side, niclosamide does have a high margin of safety in dogs and cats (and many other species) and does not tend to get absorbed systemically

into the animal's body (i.e. much safer).

How it works 1:

Cestode tapeworms do not "ingest food" via a mouth like many other kinds of parasitic

worms (e.g. nematodes like hookworms and roundworms) do. The tapeworm's head with its spiny rostellum and numerous suckers is used mainly for hanging on to the host's intestinal tract. The tapeworm does not "eat" food through its head. In order to take up nutrients (mainly glucose and galactose sugars

and certain amino acids) from the animal's intestinal tract, the tapeworm must be able to

absorb these nutrients across the surface of its body (i.e. food is essentially

absorbed through the tapeworm's skin such that a tapeworm can be considered to be just one giant

nutrient-soaking unit floating within the intestinal tract). It is because of this massive

surface area for absorbing and stealing nutrients from the host's intestinal tract that

hosts with severe tapeworm burdens can become so malnourished and starved of nutrition.

One of the actions of niclosamide is to prevent the tapeworm from absorbing glucose

from the animal host's intestinal tract. Glucose is the major sugar that the tapeworm

must have access to if it is to generate energy inside of its body (in the form of ATP -

adenosine triphosphate) and survive. If it can not take up glucose, a tapeworm will eventually run out of energy and die.

Side note - Tapeworms can also take up galactose, another form of sugar molecule, from the host animal's intestines (I am not sure whether niclosamide affects the uptake of this

sugar by the tapeworm as it does with glucose). Galactose is a sugar that more advanced animal species can convert into various energy forms, however, in the tapeworm this sugar seems to mainly be taken up to be used in the manufacture and reinforcement of certain structural components of the tapeworm body. It does not seem to be used as an energy fuel source in the way glucose is.

When a tapeworm takes in glucose from the host's intestinal tract, it uses some of this

glucose immediately to make energy for itself and it transforms the excess glucose taken in into

a product called glycogen. Glycogen is a storage form of glucose that the tapeworm can call on when access to outside glucose is in short-supply (as seen when a host animal is 'between

meals' or fasting). When a host animal has just fed (particularly if it has just eaten very glucose-rich, sugary food), the tapeworm's body gets bathed in loads of glucose, pouring down the intestinal

tract from the stomach. The worm absorbs heaps of this glucose and makes heaps of energy. When the

host animal is fasting, however, or between feeds, then no external glucose comes to the tapeworm

via way of the animal's intestinal tract. In these conditions, the tapeworm must liberate

glucose from its own internal stores of glycogen if it is to be able to make energy and go on living.

How it works 2:

Tapeworms are "facultative anaerobes" meaning that, depending on the amount of oxygen they have available to them

in their environment (i.e. inside the host intestinal tract), they can make use of both aerobic (oxygen-requiring) and anaerobic (oxygen-free) means of energy production.

When a tapeworm has little or no access to environmental oxygen (a common situation encountered inside of a host animal intestinal tract), it can create its own energy (ATP) from the catabolism of glucose molecules by making use of particular energy-producing chemical-reaction pathways that do not require the consumption and reaction of oxygen molecules. This is termed "anaerobic"

energy production. Alternatively, when that same tapeworm parasite gains access to environmental oxygen (e.g. the animal

host has swallowed lots of air during food consumption, causing the tapeworm in the intestine to be exposed

to oxygenated gases), it can then create its own energy (ATP) from the catabolism of glucose molecules by making use of particular energy-producing chemical-reaction pathways that do require the consumption and reaction of oxygen molecules. This is termed "aerobic"

energy production.

It is an amazing feat of adaptation. The environment inside of an animal intestinal tract

is obviously very variable with regard to the amount of oxygen contained within it and so the tapeworm

parasite has adapted to be capable of making energy from glucose regardless of whether oxygen is present there or not.

Of the two methods of energy production, anaerobic energy production seems to be the method that is more commonly utilized by the tapeworm parasite (oxygen availability is obviously

often restricted in the host intestinal tract). These anaerobic chemical reaction pathways that the tapeworm predominantly uses to generate energy (ATP) are fairly inefficient and low yielding. Only 1 or 2 ATP energy molecules are made from each glucose molecule using the tapeworm's anaerobic

energy-production system. This is much less than the number of molecules of ATP that get made from each glucose molecule using the highly-efficient, high-ATP-yield, oxygen-requiring pathways

(oxidative-phosphorylation-like pathways) of the aerobic method of energy manufacture.

It thus follows that tapeworms do better under oxygenated environmental conditions - they just don't

get exposed to these oxygenated conditions all that often. Despite the inefficiency of its predominantly-anaerobic means of energy production, however, the system seems to work just fine for the tapeworm,

overall.

Niclosamide is thought to inhibit the anaerobic chemical pathways that the tapeworm

uses in order to make its energy by anaerobic means. By uncoupling these pathways, the drug causes the tapeworm

to be unable to manufacture ATP energy during times of low-oxygen and, as a result, the worm's internal processes

shut down and it dies.

Side note - One text [ref 5] said that niclosamide also inhibits the Kreb Cycle: part of the highly-efficient, oxygen-requiring system of ATP energy production that is so vital

in aerobic energy production (the tapeworm's alternative means of making energy). Given that adult tapeworms make most of their energy by anaerobic means rather than

oxygen-requiring means, it is likely that the Kreb Cycle is not very important to them

(another text supported this, saying that tapeworms have little need for a Kreb Cycle [ref 4]). It thus follows that inhibition of the Kreb Cycle can not be the sole means by which niclosamide works to kill tapeworms - if a tapeworm can live anaerobically, without aerobic methods of energy production

(where the Kreb Cycle is needed), then inhibition of this Kreb Cycle alone is unlikely to kill it.

Author's note: If niclosamide does also kill off the Kreb Cycle, the tapeworm will be unable to

fall back onto aerobic means of energy production (provided oxygen is available) once the niclosamide

has knocked out the anaerobic energy system. If niclosamide knocks out both the aerobic and

anaerobic energy systems, then the tapeworm will definitely not be able to make energy. This will

certainly lead to its death.

Features of niclosamide:

- Kills a wide range of cestode (tapeworm) species in people and animals.

- Kills a wide range of cestode parasites that are present in livestock animals like deer, goats, cattle, horses

and sheep (e.g. Moniezia, Thysanoma, Anoplocephala).

- Kills Taenia species to excellent effect.

- Kills Hymenolepis species like H. nana of mice.

- Does not kill Schistosoma or any intermediate larval tapeworm forms.

- It is approved for killing adult Dipylidium caninum flea tapeworms, but its effect and reliability is variable (less effective than praziquantel).

- It does not kill adult Echinococcus granulosus or Echinococcus multilocularis hydatid tapeworms, making it unsatisfactory as an allwormer ingredient in dogs.

- Niclosamide, given orally, does not absorb systemically into the host animal's body. This feature

makes niclosamide very safe to use on intestinal tapeworm infestations, but ineffective against internal parasite forms like Schistosoma and larval tapeworms.

- An overnight fast is recommended before giving niclosamide to an animal (food can reduce the ability of the drug to make contact with the tapeworm parasites in the gut).

- Niclosamide has a wide safety margin and is difficult to overdose.

- Niclosamide is thought to be safe in pregnant and breeding animals (check with your vet).

- Niclosamide is toxic to fish and waterways.

World Health Organisation Data Sheet for Niclosamide -

http://www.inchem.org/documents/pds/pds/pest63_e.htm

NOTE - Please read our disclaimer before attempting to self-diagnose and dose your animals with

any drugs mentioned on these pages. Pet Informed is a general advice website only and mistakes can be

made - we always recommend that you double-check any of our information with your own vet.

Other Anti-Cestodal Drugs.

Aside from praziquantel and niclosamide, there are other anti-cestodal drugs out there that have some activity against many of the parasitic tapeworms, including

Dipylidium, infesting dogs and cats. I will not make huge mention of them, aside from the basic points below, because many of them are going out of fashion, many are hard to get, most have only a very narrow range of tapeworm activity and some have significantly toxic side effects when used in domestic animals.

I would not recommend using any of the

below-mentioned drugs to treat tapeworms in domestic pets (especially dogs and cats) if you have access to

praziquantel (see your vet). Praziquantel is the best as far as I can tell.

Bunamidine hydrochloride:

Has been used on tapeworms in dogs and cats.

Good activity against

Taenia. Fair to good activity against

Echinococcus, but variable activity against

Dipylidium (not reliable for breaking the flea tapeworm life cycle).

Must be given on an empty stomach.

Has been known to have significant toxic side effects, including the death of pets.

Dichlorophen:

Has been used on tapeworms in dogs and cats.

Good activity against

Taenia. Fair to good activity against

Dipylidium, but unreliable against

Echinococcus (not reliable for breaking the hydatid tapeworm life cycle).

Minimal absorption from the intestinal tract, so toxicity is thought to be low (when used orally).

Hexachlorophene:

Mainly used to kill tapeworms and flukes in livestock animals, not domestic pets.

Good activity against

Taenia and

Echinococcus (I'm not sure about its effects on the flea tapeworm life cycle).

Tests on dogs have found that this drug can have significant toxic side effects in this species (cats unknown).

Bithionol:

Has been used on tapeworms in dogs and cats and many other animal species.

Good activity against Taenia, but variable to low activity against

Dipylidium (not reliable for breaking the flea tapeworm life cycle).

Has been known to have toxic side effects in domestic pets (vomiting, diarrhea), but for the most part is

well-tolerated by dogs and cats.

Benzimidazole drugs (Mebendazole, Fenbendazole and so on):

Many types of benzimidazole drugs have been studied in order to assess their effects against tapeworms in dogs and cats.

Most of them show good activity against Taenia and some even show good activity against Echinococcus, but none of them

is any good for treating Dipylidium (i.e. not reliable for breaking the flea tapeworm life cycle).

Benzimidazoles have been known to have significant toxic side effects in dogs and cats and other species.

NOTE - Please read our disclaimer before attempting to self-diagnose and dose your animals with

any drugs mentioned on these pages. Pet Informed is a general advice website only and mistakes can be

made - we always recommend that you double-check any of our information with your own vet.

3) Your flea tapeworm life cycle links:

To go from this flea tapeworm life cycle page to the Pet Informed Home Page, click here.

To go from this flea tape worm lifecycle page to the Flea Life Cycle and Flea Control page, click here.

To go from this flea tapeworm lifecycle page to the Lice Information and Lice Treatment page, click here.

Flea Tapeworm Life Cycle References and Suggested Readings:

1) Helminths. In Bowman DD, Lynn RC, Eberhard ML editors: Parasitology for Veterinarians, USA, 2003, Elsevier Science.

2) Phylum Platyhelminthes. In Hobbs RP, Thompson ARC, Lymbery AJ: Parasitology, Perth, 1999, Murdoch University.

3) Tapeworms. In Schmidt GD, Roberts LS: Foundations of Parasitology, 6th ed., Singapore, 2000, McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

4) Cestoidea: Form Function and Classification of the Tapeworms. In Schmidt GD, Roberts LS: Foundations of Parasitology, 6th ed., Singapore, 2000, McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

5) Roberson EL, Anticestodal and Antitrematodal Drugs. In Booth NH, Mc Donald LE: Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 6th ed., Iowa, 1988, Iowa State University Press.

Pet Informed is not in any way affiliated with any of the companies whose products

appear in images or information contained within this flea tapeworm life cycle article or our related articles. Any images or mentions, made by Pet Informed, are only used in order to illustrate certain points being made in the article. Pet Informed receives no commercial or reputational benefit from any companies

for mentioning their products and can not make any guarantees or claims, either positive or negative, about these companies' products, customer service or business practices. Pet Informed can not and will not take any responsibility for any death, damage, illness, injury or loss of reputation and business

or for any environmental damage that occurs should you choose to use one of the mentioned products on your pets, poultry or livestock (commercial or otherwise) or indoors or outdoors environments. Do your homework and research all tapeworm products carefully before using any tapeworm treatment products on your animals or their environments.

Copyright April 20, 2010, Dr. O'Meara, www.pet-informed-veterinary-advice-online.com.

All images, both photographic and drawn, contained on this site are the property of Dr. O'Meara and are protected under copyright. They can not be used or reproduced without my written permission.

Frontline Spray, Frontline Top Spot Cat, Frontline Top Spot Dog and Frontline Plus are registered trademarks of Merial Australia Pty Ltd.

Milbemax is a registered trademark of Novartis Animal Health Australasia Pty Ltd.

Fenpral Intestinal Wormer for Dogs is a registered trademark of Arkolette Pty Ltd / Riverside Veterinary Products.

Please note: the aforementioned tapeworm prevention, flea tapeworm control and flea tapeworm

treatment guidelines and information on the flea tapeworm life cycle are general information and recommendations only. The information provided is based on published information and on relevant veterinary literature and publications and my own experience as a practicing veterinarian.

The advice given is appropriate to the vast majority of pet owners, however, given

the large range of tapeworm varieties out there and the large range of tapeworm medication types and tapeworm prevention and control protocols now available, owners should take it upon themselves to ask their own veterinarian what treatment and flea tapeworm prevention schedules s/he is using so as to be certain what to do. Owners with specific circumstances (e.g. high and repeated flea tapeworm infestation burdens in their pet; pregnant bitches and queens; very young puppies and kittens;

severe flea or lice infestations; livestock and poultry producers; multiple-dog and cat environments;

animals on immune-suppressant medicines; animals with immunosuppressant diseases or conditions; owners of sick and

debilitated animals etc. etc.) should ask their vet what the safest and most effective flea tapeworm control protocol is for their situation.

Please note: the scientific tapeworm names mentioned in this flea tapeworm life cycle article are only current as

of the date of this web-page's copyright date and the dates of my references. Parasite scientific names are constantly being reviewed and changed as new scientific information becomes available and names that are current now may alter in the future.

Every individual tapeworm segment is essentially an individual egg-producing reproductive factory. Tapeworms are hermaphrodites (bearing both male and female sex structures). Each proglottid segment has its own

testicular-type organ structure/s and its own uterine organ structure/s (for creating and maturing eggs)

and every single proglottid is, therefore, capable of producing and fertilising its own set of eggs, once mature. The small-sized proglottids nearest the anchoring 'head' of the flea tapeworm are the most under-developed and immature of all the tapeworm's segments and are, consequently, incapable of creating fertile eggs because of their under-developed state. The large proglottids nearest the 'tail-end' of the tapeworm are the most mature of all the tapeworm's segments and are capable of having their eggs fertilized and matured into an embryo-bearing state.

Every individual tapeworm segment is essentially an individual egg-producing reproductive factory. Tapeworms are hermaphrodites (bearing both male and female sex structures). Each proglottid segment has its own

testicular-type organ structure/s and its own uterine organ structure/s (for creating and maturing eggs)

and every single proglottid is, therefore, capable of producing and fertilising its own set of eggs, once mature. The small-sized proglottids nearest the anchoring 'head' of the flea tapeworm are the most under-developed and immature of all the tapeworm's segments and are, consequently, incapable of creating fertile eggs because of their under-developed state. The large proglottids nearest the 'tail-end' of the tapeworm are the most mature of all the tapeworm's segments and are capable of having their eggs fertilized and matured into an embryo-bearing state.  When a proglottid enlarges and develops to a certain stage, becoming sexually mature, gametes (essentially sperm) from the male testicular components of the proglottid

segment fertilize the eggs (female) present within that or a nearby proglottid segment (as mentioned before, there can be cross-fertilisation from proglottid to proglottid). The newly fertilised tapeworm eggs mature

inside of the proglottid, developing embryos inside of them, and the proglottid continues to grow in size. A proglottid that contains fertilized eggs inside is said to be "gravid" (i.e. a gravid proglottid).

When a proglottid enlarges and develops to a certain stage, becoming sexually mature, gametes (essentially sperm) from the male testicular components of the proglottid

segment fertilize the eggs (female) present within that or a nearby proglottid segment (as mentioned before, there can be cross-fertilisation from proglottid to proglottid). The newly fertilised tapeworm eggs mature

inside of the proglottid, developing embryos inside of them, and the proglottid continues to grow in size. A proglottid that contains fertilized eggs inside is said to be "gravid" (i.e. a gravid proglottid).

An intermediate host insect (usually a flea larva, but sometimes a biting louse) consumes the tapeworm egg packets present in the environment. Normally, flea larvae survive

on a diet of flea excreta (flea dirt) and environmental dander, but they will happily consume

tasty tapeworm eggs if they come across them! When the intermediate host consumes the tapeworm egg packet, the tapeworm embryos survive and hatch from their eggs inside of the body of

the intermediate host. Here the embryos develop further into an intermediate tapeworm stage called a cysticercoid. The cysticercoid stage of the flea tapeworm life cycle is able to survive the pupal stage

of the flea life cycle (when the flea transforms from flea larva into an adult flea by way of a cocoon).

Cysticercoids appearing inside of adult fleas and lice are infectious to the definitive host animal.

An intermediate host insect (usually a flea larva, but sometimes a biting louse) consumes the tapeworm egg packets present in the environment. Normally, flea larvae survive

on a diet of flea excreta (flea dirt) and environmental dander, but they will happily consume

tasty tapeworm eggs if they come across them! When the intermediate host consumes the tapeworm egg packet, the tapeworm embryos survive and hatch from their eggs inside of the body of

the intermediate host. Here the embryos develop further into an intermediate tapeworm stage called a cysticercoid. The cysticercoid stage of the flea tapeworm life cycle is able to survive the pupal stage

of the flea life cycle (when the flea transforms from flea larva into an adult flea by way of a cocoon).

Cysticercoids appearing inside of adult fleas and lice are infectious to the definitive host animal.  Author's note: an intermediate host animal (e.g. flea or louse insect in this case) is a host

animal that the tapeworm parasite needs to infest if it is to be able to complete part of its lifecycle. In this case, the flea tapeworm needs to infest an insect host if it is to hatch from the tapeworm

egg and transform from an embryonic (hexacanth) stage to an intermediate (cysticercoid) stage. The parasitic tape worm is unable to reach adulthood and sexual maturity inside of an intermediate host animal and needs to later enter the body of a definitive host animal like a dog or cat in order

to achieve sexual and reproductive maturity.

Author's note: an intermediate host animal (e.g. flea or louse insect in this case) is a host

animal that the tapeworm parasite needs to infest if it is to be able to complete part of its lifecycle. In this case, the flea tapeworm needs to infest an insect host if it is to hatch from the tapeworm

egg and transform from an embryonic (hexacanth) stage to an intermediate (cysticercoid) stage. The parasitic tape worm is unable to reach adulthood and sexual maturity inside of an intermediate host animal and needs to later enter the body of a definitive host animal like a dog or cat in order

to achieve sexual and reproductive maturity.