Tapeworm in Cats - Taenia taeniaeformis Feline Tapeworms.

This 'Tapeworm in cats' page contains a very simplified explanation

of the life cycle, symptoms, treatment and prevention of one of the major species of parasitic tapeworms in cats:

Taenia taeniaeformis. The page is meant as a very basic, practical overview of the life cycle, medical significance and control of this particular

species of feline tapeworm as it affects domestic cats and cat owners.

For our much more detailed page on

Taenia tapeworms, including

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm in cats

and

Taenia tapeworms in people and dogs, please visit our main

Taenia tapeworm page. I've kept the language basic on my

Taenia page for ease of understanding, but those of you who like to read in some detail should find loads of handy and interesting information

about this tapeworm Genus. Enjoy.

Taenia taeniaeformis Tapeworm in Cats - Contents:

1) The Taenia taeniaeformis cat tapeworm life cycle diagram.

2) Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm symptoms in definitive host cats.

3) Treatment and prevention of Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm in cats.

1) Tapeworm in Cats - The Life Cycle of feline Taenia (Taenia taeniaeformis).

1) Tapeworm in Cats - The Life Cycle of feline Taenia (Taenia taeniaeformis).

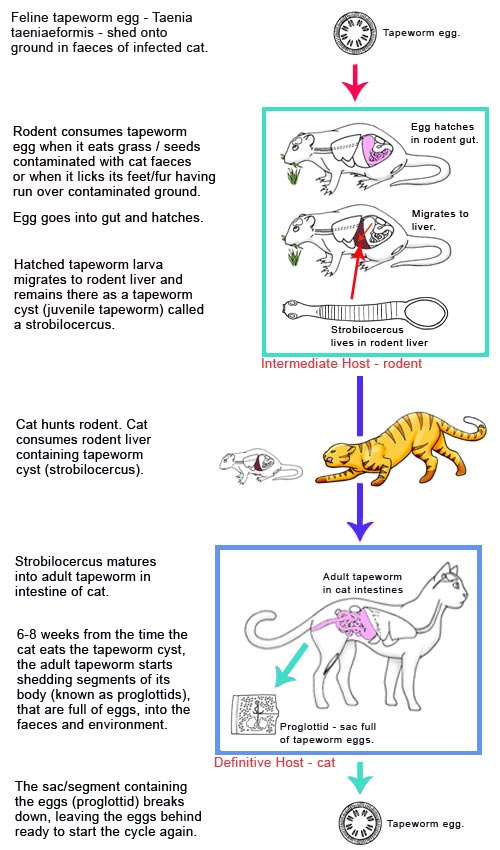

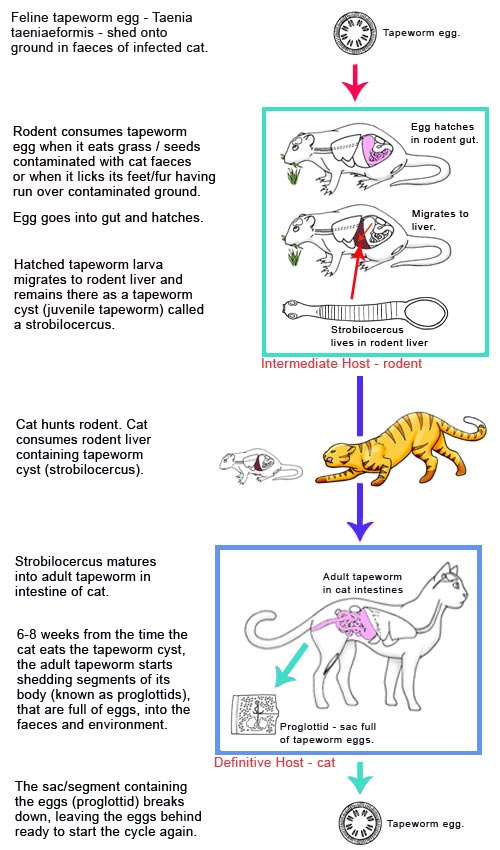

Taenia Tapeworm in Cats Diagram:

Taenia Tapeworm in Cats Diagram: The above image contains a diagram of the life cycle of one of the major cat tapeworms -

Taenia taeniaeformis.

The diagram shows the complete cycle of this Taeniid tapeworm's existence - from egg to adult tapeworm to egg again (with the next generation of tapeworm eggs) - within the bodies of two different, yet both equally essential, host animal species: the intermediate host rodent (e.g. vole, rat) and the definitive host cat.

Note - This page predominantly deals with

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm infestations in domestic house cats, however, it is important to note that wild felids (e.g. lynxes)

and also wild and domestic canids (dogs, wolves and so on) can and do get adult

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworms in their intestines. The cat is the major definitive host, however, so this is the species I will be discussing.

Adult

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworms live and feed in the small intestines of cats. These carnivorous feline

hosts are termed

definitive hosts with regard to the

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm life cycle because they are

the hosts that this parasitic Taenia tapeworm species was intended for and that the tapeworm organism reaches adulthood and sexual maturity in.

The body of an adult Taeniid tapeworm like

Taenia taeniaeformis is made up of hundreds to thousands of individual segments, termed

proglottids. These segments progress in size and maturity as one travels down the tapeworm's body: ranging from very tiny (those proglottids nearest the

scolex or 'head' of the tapeworm) right through to very large (easily seen with the naked eye).

Every individual

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm segment is essentially an individual egg-producing reproductive factory. Tapeworms are hermaphrodites (bearing both male and female sex structures). Each proglottid segment has its own testicular-type organ structure/s (for creating male gametes or 'sperm')

and its own uterine organ structure/s (for creating and maturing eggs)

and every single proglottid is, therefore, capable of producing and fertilizing its own set of eggs, once mature. The small-sized proglottids nearest the anchoring 'head' of the

Taenia tapeworm are the most under-developed and immature of all the tapeworm's segments and are, consequently, incapable of creating fertile eggs because of their under-developed state. The large proglottids nearest the 'tail-end' of the

Taenia tapeworm are the most mature of all the tapeworm's segments and are capable of having their eggs fertilized and matured into an embryo-bearing state.

Author's note: Because every individual proglottid contains both male and female sex organs, it is possible for a single proglottid to 'self-fertilise' (self-inseminate its

own eggs). And this

certainly does occur. In reality, however, it is probably much more common for individual proglottids to 'cross-fertilise' - inseminating other, nearby proglottids on the same tapeworm 'chain' and/or even proglottids located on completely separate tapeworms (i.e. other mature

Taenia taeniaeformis cat tapeworms that just happen to be living within reach). This makes for a better spread of tapeworm genes and lessens the degree of in-breeding.

When a proglottid enlarges and develops to a certain stage and size, becoming sexually mature, gametes (essentially sperm) from the male testicular components of that proglottid segment

or a nearby proglottid segment (as mentioned before, there can be cross-fertilization from proglottid to proglottid)

fertilize the eggs (female) present within that proglottid segment. The newly fertilized

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm eggs mature inside of the proglottid, developing embryos inside of them, and the proglottid continues to grow in size. A proglottid that contains fertilized eggs is said to be "gravid" (i.e. a gravid proglottid).

Once the fertilized tapeworm eggs are fully-matured (ready to enter the next stage of the

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm life cycle), the now-enlarged, fat proglottid segment bearing them breaks away from the main body of the feline tapeworm. This proglottid segment exits the definitive host cat's body intact via the anus. The segment either physically

crawls from the anus of the cat by contracting its muscles and creeping along (people spotting these crawling

proglottid segments often think that their cat is infested with fly maggots) or it is voided in the stools as the cat defecates. Sometimes a large section of the

Taenia taeniaeformis

tapeworm (several proglottids in length) breaks away and is voided in the cat's feces. These longer sections

of feline tapeworm are almost invariably found by cat owners, often causing alarm, particularly if the cat toilets in

a litter tray that the owner has to clean.

Once outside of the cat, the shed proglottid segment continues to writhe, breaking apart and expelling its fertilized, matured tapeworm eggs into the environment as it does so. Taeniids like

Taenia taeniaeformis lack a pore for the eggs to come out of and so the proglottid needs to physically split open to release them. The eggs of

Taenia taeniaeformis are expelled from the proglottid segment individually.

Each tapeworm egg is infective the moment it exits the proglottid and generally contains an embryo (called a

hexacanth) that has the potential to develop into an adult

Taenia taeniaeformis feline tapeworm at some point in the future (all going to plan with regard to the life cycle requirements of this cat tapeworm species, of course).

When a rodent

intermediate host (e.g. rat, mouse, vole) consumes the egg/s of the feline tapeworm, the tapeworm embryos contained inside of these eggs survive ingestion and hatch from their eggs within the intestines of the intermediate host animal. These

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm embryos (termed

hexacanths or "first stage larvae") migrate across the intestinal wall and establish themselves within the

liver of the intermediate host rodent. Here they develop and enlarge further, forming a fluid-filled, thin-walled, cystic, secondary larval tapeworm stage called a "tapeworm cyst" or "second stage larva." The technical term

for the second-stage larva or "cyst" of the

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm is a

"strobilocercus" (see section 1 of our

main Taenia page for detailed information on the various forms of tapeworm larval cyst, including the strobilocercus).

The strobilocercus larva of

Taenia taeniaeformis, imbedded in the liver of the rodent intermediate host, takes on the form of a spherical, expanding, fluid-filled, bladder-like structure with a thin, almost-see-through, outer wall. These larval "cysts" are typically very small (after all, they need to fit inside of a tiny rodent liver).

The inner lining of the larval tapeworm strobilocercus cyst or 'bladder' is called a

"germinal lining". It actively

generates within the fluidy, cystic confines one miniature larval tapeworm "head" or "scolex" (this tiny tapeworm head is termed a scolex, 'scolice or protoscolice). This tiny tapeworm "head" is the individual unit that will go on to become the adult tapeworm when the

Taenia taeniaeformis larval cyst is later consumed by the definitive host cat when it hunts and eats the infested rodent.

Note on terminology: an intermediate host animal (e.g. rodent animal in this case) is a host

animal that the

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm parasite needs to infest if it is to be able to complete an essential part of its lifecycle. In this case, the

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm needs to infest a rodent host (generally a herbivore or omnivore) if it is to hatch from the tapeworm egg and transform into a second stage larval cyst

(strobilocercus). This parasitic tape worm is

unable to reach adulthood and sexual maturity inside of the intermediate host animal and needs to later enter the body of a definitive host animal (cat) in order

to achieve sexual and reproductive maturity.

Author's note: The

Taenia taeniaeformis feline tapeworm eggs are typically consumed by the rodent hosts in a pasture or forest-type environmental setting. The infested definitive host feline defecates onto the pasture (e.g. pasture on a farm) or in the forest (e.g. bushland, national park setting) and, in doing so, sheds infective

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm eggs into this environment. The organic fecal matter breaks down in days, but the resistant

tapeworm eggs remain in the environment, speckled invisibly across the grass. The intermediate host rodent

consumes the tapeworm eggs, thereby becoming infested with larval strobilocerci, by eating the contaminated pasture contained within this forest or farmland setting. On some occasions, coprophagous (feces-eating) intermediate host rodents will even consume entire, freshly-shed, gravid proglottids (i.e. through the ingestion of fresh definitive host feces), resulting in the uptake of hundreds of tapeworm eggs all at once by that intermediate host.

The definitive host cat becomes infested with the adult tapeworm form of the

Taenia taeniaeformis life cycle by consuming the larval-cyst-infested organs of an intermediate host rodent that has become infested with the strobilocercus forms of

Taenia taeniaeformis.

The definitive host feline must eat infective, fertile strobilocercus cysts, containing active

protoscolices, if it is to become infested with the adult

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm forms.

This sort of consumption is common in the animal world, where cats, both wild and domestic, feast on the fresh, warm offal of their freshly killed prey (e.g. rats, mice, voles).

When the definitive host cat consumes the tapeworm-cyst-infested intermediate host tissues, the mini-tapeworm

protoscolices (which up until now have been 'invaginated' - held inverted inside of their cystic bladder support structures) evaginate and poke out of their bladder-like support structures. The supportive bladder-like structures digest away and only the head and neck of the protoscolex is left, floating freely within the small intestinal

tract of the definitive host cat. These protoscolices are the individual units that will develop into the

final-stage adult

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworms. They will attach

to the wall of the cat host's intestinal tract and begin feeding and budding off proglottid segments. Eventually mature

Taenia taeniaeformis proglottids will develop, be fertilised and become egg-laden. Egg-containing proglottids will eventually start shedding out into the cat's droppings.

The first

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm eggs will start appearing in the definitive host feline's environment anywhere from 5-11 weeks (average is around 6-8 weeks - stated in my diagram) after the

Taenia-cyst-infested intermediate host rodent was first ingested [ref 10]. This 5-11 week period is termed the "pre-patent period".

Untreated, the adult

Taenia worm will normally survive for about 12-18 months in the host cat [ref 10].

Thus the life cycle of

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm in cats continues ...

Author's note: Each

Taenia tapeworm life cycle tends to be most successful and prevalent

when the 'right' definitive hosts and intermediate hosts for that particular species of Taeniid parasite live and feed in close proximity to one another (which makes obvious sense). Strong tapeworm life cycles tend to establish in environments between animals that have a natural host-prey relationship and this is what is seen

with

Taenia taeniaeformis. This particular tapeworm life cycle is perfectly adapted to a lifestyle

where cats and rodents co-exist as predators and prey. The infested cat defecates

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm eggs onto the grass, infesting the local herbivorous rodent population

with hepatic strobilocercus cysts that are later consumed by the cat when

it hunts and consumes the rodents. Perfectly logical for the tapeworm parasite and thus it survives

from generation to generation.

2) Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm symptoms in definitive host cats.

2) Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm symptoms in definitive host cats.

Adult

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworms located in the small intestinal tracts of cats can pose a variety of problems including:

- non-specific intestinal disturbances - tapeworms can produce some non-specific signs of intestinal discomfort and pain (e.g. colic signs) in animals and humans. Tapeworm afflicted humans often complain of cramping and nausea: signs that are generally difficult to ascribe to animals, but which probably do occur in them also. I once had a cat with Spirometra tapeworm

infestation present to my vet clinic with non-specific signs of on-off appetite, restlessness, lethargy and "not seeming right." None of the signs specifically pointed to tapeworm infestation and it took a routine

fecal float to make the diagnosis and find the right treatment.

- vomiting - I have personally seen cats with tapeworm parasites present to the vet clinic with vomiting.

- non-specific appetite changes - tapeworms can cause some cats

to go off their food or to become fussy or picky about their eating habits (this appetite loss is possibly the result of such factors as abdominal pain and nausea - described above). In contrast, certain other individuals

develop a ravenous appetite in the face of heavy tapeworm infestations because they are competing with

the parasite/s for nutrients (the cats need to physically eat more to provide enough nutrition for both themselves and the worms).

- body weakness, headaches, dizziness, irritability and delirium - sometimes described in human tapeworm infestations, non-specific signs of weakness, headache and dizziness may occur in animals also. Whether we would ever actually be likely to diagnose these sorts of non-specific signs in our cats is the real question, however - if our felines can not actually describe sensations of dizziness or headache to us humans, then how would we ever know?

- malnutrition - very large numbers of adult Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworms present in the intestinal tracts of cats (particularly kittens) can result in the malabsorption of nutrients (food) by the infested animal. This can cause the tapeworm-parasitised cat to not receive the nutrition it needs (i.e. to not absorb its food properly), resulting in malnourishment, weight loss, ill-thrift and poor growth.

- poor coat and hair quality - severe malnutrition and malabsorption of vitamins, minerals and proteins can result in reduced quality of the haircoat - e.g. brittleness, thinning, coarseness and loss of lustre of the coat.

- intestinal irritation and diarrhea - when an adult tapeworm inhabits the small intestine of a cat, it finds a suitable site along the lining of the intestinal wall and grasps on to it using suckers (acetabula) and a spiny anchor-like organ called a rostellum. This spiky tapeworm grip is irritating to the wall of the small intestine, creating discomfort for the host cat and alterations in intestinal motility

and regional intestinal mucus secretions, which can result in diarrhea (note that diarrhea is mainly seen only in very heavy tapeworm infestations). In some individuals, the penetrating rostellum causes a severe inflammatory, allergic reaction within the host's intestine (the host's immune system actively rejects and attacks the tapeworm proteins), causing the animal host to exhibit abdominal pain and diarrhea.

- intestinal blockage - it is possible for massive tapeworm infestations to block up

the intestines of cats (especially small kittens), producing signs of intestinal obstruction (e.g. vomiting, shock and even death). This is not common (very rare), but it can occur if worm burdens are large and/or if someone deworms the infested animal, killing all of the worms in one hit (the tapeworms all die and let go of their intestinal attachments at the same time, resulting in a vast mass of deceased tapeworms flowing down the cat intestinal tract all at once and causing blockage).

- perineal or anal irritation and scooting - the migration of tapeworm segments from the anuses of infested cats can result in itching and irritation of the anus. The cat

will normally respond by excessively licking and chewing at the anus in order to remove the irritation. If it can not reach the anus, the cat may drag and rub its bottom on the ground to remove the irritation. This bottom rubbing, called "scooting", is usually a sign of anal or perineal irritation and evacuating tapeworms can be one cause of this (side note - anal gland impaction is a much more common cause of scooting in cats, however, it can be a sign seen in 'wormy' animals).

- annoyance - most pet owners don't like to see or hear their cats fastidiously licking their bottoms or rubbing their butts along the carpet. This annoyance is compounded when the rubbing activities result in fecal staining of floors or if tapeworm segments are actually seen extruding

from the cat's anus;

- gross-out factor - the sight of long tapeworms in the feces and/or white,

grub-like tapeworm segments crawling from a cat's anus is revolting and off-putting to many people who see such infestations as a sign of 'dirtiness' and 'disease' (even though clean cats can and do get tapeworms of course).

Of all of the problems mentioned above, the disgust factor (gross-out factor) is probably the most

significant and commonly seen in the vet clinic. Problems like malnutrition, intestinal irritation, perineal irritation, diarrhea, intestinal blockage and poor coat quality are seen of course with

Taenia taeniaeformis infestations, however, it must be stated that it generally

requires a massive tapeworm burden to be present before such severe signs are likely to be encountered

in practice. As a vet in Australia, I have not personally seen an adult

Taenia tapeworm burden so massive as to result in a major malabsorption or intestinal disturbance issue (although under certain conditions

whereby cats are catching and consuming plenty of rodent prey, I do not doubt that it probably occurs). Far more commonly, people come to me in a panic because they have just found a large, white worm in the droppings of their cat or seen a pale, fat, maggot-looking tapeworm segment slither out of the anus of their kitten. In these quite common situations, the animal in question is generally healthy and fine (it just needs worming treatment) - it's the owner who's the one needing the reassurance (and the smelling salts)!

Additional note: Don't forget the effect of the cystic larval strobilocercus forms on the health of

the intermediate host rodents. We don't tend to think about these animals so much because they are normally just

seen as wild, unwanted vermin, however, pet rodents can and do get infected. Large numbers of larval

Taenia taeniaeformis cysts can cause severe liver damage to host rodents and there have been cases

of rodent hepatic cancer caused by the invasion of such parasites. Reference 11 contains an interesting case of a

Taenia taeniaeformis implicated liver cancer in a pet rat.

3) Treatment and prevention of Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworms in cats.

Adult Taeniid tapeworm in cats can be eliminated from the animal's intestinal tract

using tapeworm-specific anti-cestodal medications like praziquantel and niclosamide. Other anti-cestodal

drugs are also available (see our main Taenia page for other tapeworm in cats treatment options), but are

much less commonly used due to safety, efficacy and ease-of-availability limitations.

Of all the drugs used to kill tapeworms in cats, praziquantel is the anticestodal drug most commonly included in the majority of commercially-available cat 'all-wormers'. This tapeworm drug

is highly effective on pretty much all species of adult tapeworm in cats, not just Taenia taeniaeformis

(e.g. Spirometra mansoides, Dipylidium caninum). It absorbs into the animal's body rapidly following oral dosing, reaching most internal organs. It has a high safety margin and is difficult to overdose. It can be used on cats over 4 weeks of age. It can be used on pregnant and lactating animals

(note - before dosing, check with a vet to be sure that any worming product you are giving doesn't contain other ingredients that are harmful to your pregnant or lactating cat).

When an adequate dose (the dose rate of 5mg/kg commonly stated on the cat all-wormer packet is generally ample for killing Taenia taeniaeformis) of praziquantel is administered to the definitive host cat, the Taeniid tapeworms die and are voided in the animal's faeces (pet owners may find several large, dead tapeworms

in their animal's droppings following the administration of just such a wormer). This single treatment is usually curative, however, several doses may be needed to completely rid an animal of a very large tapeworm

burden (if a large tapeworm burden is suspected, the praziquantel can be repeated two-weekly for a couple of doses

to be sure of getting them all).

Author's note: Epsiprantel, an anti-cestodal drug closely related to praziquantel, can be used

to kill Taenia taeniaeformis and Dipylidium caninum tapeworms in cats. It is typically given at a rate of 2.75mg/kg to cats and, at this dose rate, is thought to be well-tolerated and quite safe in this animal species. I am unaware of the safety of epsiprantel in pregnant and lactating animals and so would not recommend it in such animals. It is also recommended that the drug NOT be given to kittens under 8 weeks of age.

Author's note: Be aware that most deworming medications (aside from some heartworm meds) do not generally last very long in a treated-cat's system. When an all-wormer is given to a cat, the worm-killing drugs work rapidly, killing off the adult worm parasites, before disappearing. The drugs do not hang around to protect the cat against subsequent tapeworm infestations. This means that should

the cat continue to eat larval-tapeworm-infested rodents in the days following

the deworming treatment, they will most likely become rapidly re-infested with adult tapeworms.

Following the ingestion of a cyst-infested intermediate host rodent, a definitive host cat can have a reproductively-mature, proglottid-shedding adult tapeworm inside of its

intestine within a mere 6-8 weeks. In high-transmission situations (e.g. a barn or farm

cat that hunts), this could mean that a pet owner may need to repeat worm (tapeworm-treat) his cat every 6-8 weeks to keep the adult tapeworm numbers under control.

The best options and tips for the ongoing control of Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworms in cats is to:

a) give the cat regular tapeworming medications - praziquantel should be given every 8 weeks (2 months)

in high-transmission situations (e.g. outdoor-roaming cats, farm cats, hunting cats) or, in low-transmission situations (e.g. indoor-only cats), as per the manufacturer's directions (generally every 3 months).

b) not allow the cat to have access to foods likely to contain larval tapeworms - essentially this means that

the cat should not be allowed to hunt and eat rodents (difficult in situations where cats are kept on as "mousers" and "ratters").

c) keep rodent populations low - by reducing the number of rodent intermediate hosts that your cat

has access to, you can greatly reduce the risk of your cat picking up feline tapeworms (Taenia taeniaeformis

species anyway).

All cats and other pets in the household should be treated for tapeworms at the same time. This helps to ensure that all animals are wormed on time and helps to ensure that parasite populations are unable

to take refuge within the "non-wormed" animals, therefore reducing the overall parasite burden

in the environment.

All pets should be weighed before worming to ensure that they receive the correct dose of all-wormer.

Although overdosing is unlikely to be a problem with safe drugs like praziquantel, under-dosing a pet can result in increased rates of parasite survival.

For more about treating tapeworms in cats, including praziquantel and niclosamide, see section 3 of our main

Taenia tapeworm page.

4) Your Taenia tapeworm in cats life cycle links:

To go from this Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworms in cats page to our main Taenia Tapeworm page, click here.

To go from this Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworms in cats page to our main Taenia Tapeworm page, click here.

To go from this Taenia tapeworm in cats life cycle page to the Pet Informed Home Page, click here.

To go from this Taenia tapeworms in cats page to the Flea Tapeworm (Dipylidium caninum) page, click here.

http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/taenia.pdf

A really nice, detailed fact sheet on all things Taenia in both human and animal hosts. The

article is written by the Centre for Food Security and Public Health and Iowa University.

Taenia Tapeworm in Cats Life Cycle References and Suggested Readings:

1) Helminths. In Bowman DD, Lynn RC, Eberhard ML editors: Parasitology for Veterinarians, USA, 2003, Elsevier Science.

2) Antihelmintics. In Bowman DD, Lynn RC, Eberhard ML editors: Parasitology for Veterinarians, USA, 2003, Elsevier Science.

3) Phylum Platyhelminthes. In Hobbs RP, Thompson ARC, Lymbery AJ: Parasitology, Perth, 1999, Murdoch University.

4) Tapeworms. In Schmidt GD, Roberts LS: Foundations of Parasitology, 6th ed., Singapore, 2000, McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

5) Cestoidea: Form Function and Classification of the Tapeworms. In Schmidt GD, Roberts LS: Foundations of Parasitology, 6th ed., Singapore, 2000, McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

6) Roberson EL, Anticestodal and Antitrematodal Drugs. In Booth NH, Mc Donald LE: Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 6th ed., Iowa, 1988, Iowa State University Press.

7) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2775987 - epsiprantel.

8) Manger BR and Brewer MD, Epsiprantel, a new tapeworm remedy. Preliminary efficacy studies in dogs and cats. British Veterinary Journal, Volume 145, Issue 4, July-August 1989, Pages 384-388.

9) Wilcox RS et al. Intestinal Obstruction Caused by Taenia taeniaeformis Infection in a Cat. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association, 45:93-96 (2009).

10) Williams JF, Shearer AM. Longevity and productivity of Taenia taeniaeformis in cats.

American Journal of Veterinary Research. 1981 Dec;42(12):2182-3.

11) Irizarry-Rovira AR, Wolf A, Bolek, M. Taenia taeniaeformis-induced Metastatic Hepatic Sarcoma in a Pet Rat (Rattus norvegicus). Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine, Volume 16, Issue 1, January 2007, Pages 45-48.

12) http://www.jstor.org/pss/3274356

13)Taenia Infections. In Centre for Food Security and Public Health: http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/taenia.pdf Iowa, 2005, Iowa State University Press.

Pet Informed is not in any way affiliated with any of the companies whose products

appear in images or information contained within this Taenia tapeworm in cats life cycle article or our related articles. Any images or mentions, made by Pet Informed, are only used in order to illustrate certain points being made in this tapeworm in cats article. Pet Informed receives no commercial or reputational benefit from any companies

for mentioning their products and can not make any guarantees or claims, either positive or negative, about these companies' products, customer service or business practices. Pet Informed can not and will not take any responsibility for any death, damage, illness, injury or loss of reputation and business

or for any environmental damage that occurs should you choose to use one of the mentioned products on your pets, poultry or livestock (commercial or otherwise) or indoors or outdoors environments. Do your homework and research all tapeworm products carefully before using any tapeworm treatment products on your animals or their environments.

Copyright July 2, 2010, Dr. O'Meara, www.pet-informed-veterinary-advice-online.com.

All images, both photographic and drawn, contained on this site are the property of Dr. O'Meara and are protected under copyright. They can not be used or reproduced without my written permission.

Please note: the aforementioned tapeworm prevention, Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm control and Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm treatment guidelines and information on the Taenia tapeworm in cats

life cycle are general information and recommendations only. The information provided is based on published information and on relevant veterinary literature and publications and my own experience as a practicing veterinarian.

The advice given is appropriate to the vast majority of cat owners, however, given

the large range of tapeworm varieties out there and the large range of tapeworm medication types and tapeworm prevention and control protocols now available, owners should take it upon themselves to ask their own veterinarian what treatment and tapeworm prevention schedules s/he is using so as to be certain what to do. Owners with specific circumstances (e.g. high and repeated tapeworm burdens in their cats; high-transmission situations; hunting situations; farm situations; pregnant and lactating queens; very young kittens; multiple-cat environments;

cats on immune-suppressant medicines; animals with immunosuppressant diseases or conditions; owners of sick and

debilitated cats etc. etc.) should ask their vet what the safest and most effective tapeworm control protocol is for their situation.

Please note: the scientific tapeworm names mentioned in this Taenia tapeworm in cats

life cycle article are only current as of the date of this web-page's copyright date and the dates of my references. Parasite scientific names are constantly being reviewed and changed as new scientific information becomes available and names that are current now may alter in the future. Note that

Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm in cats is sometimes also called Hydatigera taeniaeformis.

Common misspellings: Taenia taeniaformis, Taania taeniaformis, Taania taeniaeformis, Taenia taeniaformus, Taenia taeniaeformus.

Every individual Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm segment is essentially an individual egg-producing reproductive factory. Tapeworms are hermaphrodites (bearing both male and female sex structures). Each proglottid segment has its own testicular-type organ structure/s (for creating male gametes or 'sperm') and its own uterine organ structure/s (for creating and maturing eggs)

and every single proglottid is, therefore, capable of producing and fertilizing its own set of eggs, once mature. The small-sized proglottids nearest the anchoring 'head' of the Taenia tapeworm are the most under-developed and immature of all the tapeworm's segments and are, consequently, incapable of creating fertile eggs because of their under-developed state. The large proglottids nearest the 'tail-end' of the Taenia tapeworm are the most mature of all the tapeworm's segments and are capable of having their eggs fertilized and matured into an embryo-bearing state.

Every individual Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm segment is essentially an individual egg-producing reproductive factory. Tapeworms are hermaphrodites (bearing both male and female sex structures). Each proglottid segment has its own testicular-type organ structure/s (for creating male gametes or 'sperm') and its own uterine organ structure/s (for creating and maturing eggs)

and every single proglottid is, therefore, capable of producing and fertilizing its own set of eggs, once mature. The small-sized proglottids nearest the anchoring 'head' of the Taenia tapeworm are the most under-developed and immature of all the tapeworm's segments and are, consequently, incapable of creating fertile eggs because of their under-developed state. The large proglottids nearest the 'tail-end' of the Taenia tapeworm are the most mature of all the tapeworm's segments and are capable of having their eggs fertilized and matured into an embryo-bearing state.