Veterinary Advice Online - Fecal Flotation.

A fecal flotation test, otherwise known as a 'fecal float', egg flotation or Fecalyzer Test (Fecalyzer, also spelled Fecalyser, being the most commonly used in-house commercial product) is a diagnostic test commonly performed in-house in most veterinary clinics as a way of diagnosing parasitism in animals. This page includes everything you, as a pet owner, might want to know about the fecal flotation tests performed by your veterinarian on your pet's stools:

A fecal flotation test, otherwise known as a 'fecal float', egg flotation or Fecalyzer Test (Fecalyzer, also spelled Fecalyser, being the most commonly used in-house commercial product) is a diagnostic test commonly performed in-house in most veterinary clinics as a way of diagnosing parasitism in animals. This page includes everything you, as a pet owner, might want to know about the fecal flotation tests performed by your veterinarian on your pet's stools:

1) Which parasites can be diagnosed on a fecal float? (section includes parasites of livestock, wildlife animals and humans).

2) Limitations of fecal flotation - parasites the test won't detect.

3) How a faecal float is performed - a great, step-by-step guide with heaps of veterinary pictures.

4) Collecting and storing stool samples for your vet to test.

5) False positive results (when is a 'significant' result not really significant?).

6) False negative results (when a 'negative' test result is not truly negative).

7) A short guide to the best fecal flotation solutions for diagnosing various parasites.

NEW! - Visit our great Fecal Float Parasite Pictures Gallery!

WARNING - IN THE INTERESTS OF PROVIDING YOU WITH COMPLETE AND DETAILED INFORMATION, THIS SITE DOES CONTAIN MEDICAL AND SURGICAL IMAGES THAT MAY DISTURB SOME READERS.

1) Which parasites can be diagnosed on a fecal float?

A few essential basics about the reproduction and egg-production of parasitic worms:

Parasitic worms:

nematodes (e.g. round worms, hook worms, whip worms);

cestodes (tapeworms) and

trematodes (flukes and flatworms), that live and feed within the intestines of dogs and cats and other animals typically reproduce by means of sexual reproduction (hermaphrodite 'male-female' worms such as tapeworms frequently self-fertilize). Fertilised female worms produce eggs containing their developing, embryonic, worm offspring (with some exceptions, worms rarely give birth to live young) and these eggs or ova pass out of the host animal, via its faeces, and into the general environment,

where they may then be ingested by a new host animal (thus continuing the life cycle of the worm).

Interestingly, it is not only the eggs of

intestinal-living worms that may be shed into

the host's faeces: the eggs of many liver-dwelling flukes pass into the faeces via the biliary ducts

of the animal and the eggs of many lungworm species enter and pass through the intestinal tract too

(a result of eggs being coughed up and swallowed by the host animal).

Author's note: some species of worm embryo develop extremely quickly within their eggs and reach

hatching-point while still inside of the host animal. In these cases, it is larval worms, not eggs, that

will be shed into the environment via the faeces. For example, the eggs of many species of lungworms

commonly hatch prior to expulsion in the faeces.

A few essential basics about the reproduction and oocyst-production of parasitic protozoans:

Unlike the parasitic worms, many species of parasitic protozoan organisms (single-celled organisms)

reproduce by means of asexual reproduction (simple cell-division), with or without additional cycles of sexual (male-female) reproduction. Which form of replication a protozoan parasite chooses at any one time depends on many factors including: the species of parasite, the life-stage of the organism (i.e. is the parasite in a juvenile stage or an adult stage of life), the area of the animal's body the parasite is located in and the species of host animal it has invaded.

Generally, the sexual reproduction stage of most protozoan parasites (protozoan species that actually

have a sexual phase) takes place in the intestines of a

definitive host animal (e.g. your dog or cat). A definitive host is the animal host species that the parasite has specifically evolved or adapted to invade and the

only species of animal in which the protozoan can undergo sexual reproduction.

When a protozoan organism is ready to reproduce sexually, instead of simply cell-dividing as occurs

with asexual reproduction, the protozoan individual undergoes a complex transformation - transforming into either a female or a male organism. The male protozoans act like semen, fertilizing the female protozoans. Following fertilisation, female protozoans transform into environmentally resistant, egg-like structures (termed oocysts) that contain developing, embryonic, protozoan offspring. These oocysts pass out of the host animal, via its faeces, and into the general environment

where they may then be ingested by a new host animal (thereby continuing the life cycle of the parasite).

Author's note: many species of intestinal-dwelling protozoan parasites that only replicate asexually (e.g.

Giardia, Entamoeba, Balantidium) also develop into hardened, environmentally

resistant cysts when passing out into the animal's faeces for the purposes of invading other hosts.

What does fecal flotation detect?

A fecal flotation test is normally used to detect the fecally-shed eggs (and sometimes the larvae) of various parasitic worm species as well as the oocysts shed into the droppings by various, replicating protozoan organisms.

This section lists the parasitic worm and protozoan species that can be detected using

fecal flotation procedures. For completeness, all major animal groups (including wild animals and man) have been given a mention, however, those of you just interested

in domestic dogs and cats need only look at section 1a.

The parasite listings I have provided are comprehensive, but certainly not exhaustive. There are literally millions of parasite species out there (far too many to mention them all!),

which infest domestic animals, livestock animals, wild animals and humans all over the world. These parasite listings grow by the day as more and more parasite species get

discovered (e.g. we've hardly touched upon the parasite species inhabiting fish, let alone the parasites that amphibians, spiders and insects might contain) and the names of the species that

we have identified are evolving; constantly changing as more becomes known and the various parasite families get reclassified by parasitologists (for example, the worm we vets used to know as

Capillaria has now been broken up into three distinct types, all with their own brand new names). So, all this being said, I hope you'll forgive me if I haven't mentioned every

parasite or if I have used any slightly outdated parasite names or classifications.

1a) Dog and cat parasites that may be diagnosed on fecal flotation.

1. Dog and cat worm species that may be diagnosed on faecal egg flotation:

Typical 'roundworms': Toxocara canis (dog), Toxocara cati (cat), Toxascaris leonina (cats, dogs).

Typical 'hookworms': Ancylostoma caninum (dog), Ancylostoma braziliense (dogs, cats), Ancylostoma tubaeforme (cat), Uncinaria stenocephala (dogs, cats).

'Whipworms': Trichuris vulpis (dog, cat).

'Tapeworms': Taenia species (dog, cat), Dipylidium caninum (dogs, cats), Echinococcus granulosus (dog), Echinococcus multilocularis (dogs, cats).

Note - most

Taenia and Dipylidium eggs exit the host animal encased within a proglottid (tapeworm segment) and, consequently, free eggs will rarely be found in the animal's faeces on a fecal float. Eggs that are released from

their proglottids into the faeces early may be detected on a fecal flotation.

Capillaria (bronchial worms): Eucoleus aerophilus, also called Capillaria aerophilus (dogs, cats - only mildly pathogenic).

Capillaria (intestinal worms): Aonchotheca putorii, also called Capillaria putorii (dogs, cats - non pathogenic, but difficult to remove with drugs).

Spirocerca: Spirocerca lupi (dog).

Gnathostoma: Gnathostoma spinigerum (dogs, cats).

Baylisascaris: Baylisascaris procyonis (dog - dangerous zoonotic risk to man).

Physaloptera: (dogs, cats).

Hymenolepis: Hymenolepis diminuta (dog).

Spirometra: Spirometra erinacei (dog, cat).

Strongyloides: Strongyloides stercoralis (dog), Strongyloides felis (cat).

Filaroides: Filaroides hirthi larvae (dog) - these fecally-shed worm larvae are relatively 'immobile' and do not readily migrate away from the animal's faeces. They

can sometimes be detected on fecal floatation, especially zinc sulfate fecal flotation.

2. Dog and cat protozoan parasites that may be diagnosed on fecal flotation:

Toxoplasma (Toxoplasmosis): Toxoplasma gondii (definitive host is the cat - oocysts are only shed into the faeces for 1-2 weeks).

Neospora (Neosporosis): Neospora caninum (shed by dog definitive hosts).

Cryptosporidium (Cryptosporidiosis): Cryptosporidium parvum, subtypes: C. felis (cat) and C. canis (dog) have been named. A small parasite, it can be difficult to find and recognise on a fecal flotation.

Giardia (Giardiasis): Giardia lamblia, also called Giardia duodenalis and Giardia intestinalis (dogs, cats).

Balantidium coli (Balantidiasis): Balantidium coli (dog - usually non-pathogenic, but can be zoonotic).

Coccidia (coccidiosis): Isospora species (Isospora canis, Isospora neorivolta, Isospora burrowsi, Isospora ohioensis in the dog and Isospora felis, Isospora rivolta in the cat); Besnoitia (cat - non pathogenic); Hammondia hammondi (cat only - non pathogenic); Hammondia heydorni (dog only - non pathogenic); Sarcocystis species (S. cruzi, S. tenella, S. capracanis, S. bertrami, S. leporum, S. hemionilatrantis, S. miescheriana in the dog and S. hirsuta, S. arieticanis, S. gigantea, S. porcifelis, S. fayeri, S. muris in the cat).

1b) Livestock parasites that may be diagnosed on fecal flotation.

1. Livestock worm species that may be diagnosed on faecal egg flotation:

Trichostrongylus: Trichostrongylus axei (sheep, horses, cattle, goats), Trichostrongylus species

(poultry).

Teladorsagia: Teladorsagia species (sheep, goats).

Ostertagia: Ostertagia ostertagi (cattle).

Haemonchus: Haemonchus contortus (barber's pole worm - ruminant animals).

Mecistocirrus: Mecistocirrus species (ruminants, pigs).

Cooperia: Cooperia species (ruminant animals).

Nematodirus: Nematodirus spathiger, Nematodirus fillicollis (sheep).

Hyostrongylus: Hyostrongylus rubidis - (swine / pigs).

Strongylus: Strongylus vulgaris, Strongylus equinus, Strongylus edentatus (horses).

Triodontophorus: Triodontophorus tenuicollis (horse).

Oesophagodontus: Oesophagodontus species (horses).

Strongyloides: Strongyloides papillosus (ruminants), Strongyloides ransomi (pig), Strongyloides westeri (horses).

Oesophagostomum: Oesophagostomum columbianum (sheep), Oesophagostomum venulosum (sheep), Oesophagostomum radiatum (ruminants, especially cattle), Oesophagostomum dentatum (pigs), Oesophagostomum brevicaudum (pigs).

Chabertia: Chabertia ovina (ruminants - sheep, cows, goats).

Bunostomum (hookworms): Bunostomum (ruminants).

Globocephalus (hookworms): Globocephalus urosubulatus (pig).

Metastrongylus (lungworm): Metastrongylus species (pig).

Ascaris: Ascaris suum (pigs).

Ascaridia: Ascaridia galli (chicken, turkey, duck), Ascaridia species in parrots and pigeons.

Parascaris: Parascaris equorum (horse).

Heterakis: Heterakis gallinarum (turkey).

Toxocara: Toxocara vitulorum (cow).

Ascarops: Ascarops species (pigs).

Physocephalus: Physocephalus species (pig).

Habronema: Habronema species (horse).

Draschia: Draschia megastoma species (horse).

Gnathostoma: Gnathostoma species (pigs).

Trichuris (whipworm): Trichuris discolor (cow), Trichuris suis (pig).

Capillaria (intestinal forms): Aonchotheca putorii (swine - non pathogenic), Aonchotheca species (ruminant - non disease-causing), Capillaria species (poultry).

Fasciola (liver flukes): Fasciola hepatica (cow, sheep, goat, horse, other livestock). Trematode (fluke) eggs

seldom float well in flotation media, however, Fasciola can occasionally be found using this test.

Paramphistomes (rumen flukes): Paramphistomum cervi (ruminants), Calicophoron calicophorum and Cotylophoron (flukes that lives in the rumen (stomach) of livestock animals). Trematode (fluke) eggs

seldom float well in flotation media, however, the Paramphistome group of flukes can occasionally be found using this test.

Moniezia (tapeworm): Moniezia species (cows, sheep, goats).

Thysaniezia (tapeworm): Thysaniezia species (cows, sheep, goats).

2. Livestock protozoan parasites that may be diagnosed on fecal flotation:

Cryptosporidium (Cryptosporidiosis): Cryptosporidium parvum Type 2 (cattle), Cryptosporidium andersoni (cows). A small parasite, it can be difficult to find and recognise on a fecal float.

Giardia (Giardiasis): Giardia lamblia, also called Giardia duodenalis and Giardia intestinalis (cattle, sheep, goats, llamas, others).

Balantidium coli (Balantidiasis): Balantidium coli (pig - usually non-pathogenic, but can be zoonotic).

Coccidia (coccidiosis): Isospora suis in pigs and many Eimeria species (Eimeria bovis, Eimeria zuernii, Eimeria alabamensis, Eimeria auburnensis in cattle,

Eimeria ovinoidalis in sheep, Eimeria species in goats, at least eight Eimeria species in pigs and Eimeria leuckarti in horses).

1c) Wildlife parasites that may be diagnosed on fecal flotation.

1. Wildlife worm species that may be diagnosed on faecal egg flotation:

Hyostrongylus: Hyostrongylus kigeziensis (gorilla).

Decrusia: Decrusia species (elephant).

Equinurbia: Equinurbia species (elephant).

Choniangium: Choniangium species (elephants).

Macropicola: Macropicola species (marsupial macropods).

Hypodontus: Hypodontus species (marsupial macropods).

Codiostomum: Codiostomum species (ostriches).

Conoweberia: Conoweberia apiostomum, Conoweberia stephanostomum (primates).

Ternidens: Ternidens deminutus (primate animals).

Syngamus: Syngamus species (birds, especially rheas).

Placoconus (hookworm): Placoconus lotoris (raccoon).

Bunostomum (hookworms): Bunostomum species (wild ruminants).

Bathmostomum (hook worms): Bathmostomum species (elephants).

Grammocephalus (hook worm): Grammocephalus species (elephant, rhinoceros).

Strongyloides: Strongyloides fuelleborne (primates), Strongyloides cebus (primates), Strongyloides ratti (rodents) and Strongyloides venezuelensis (rats) and other Strongyloides

species in elephants, marsupials, turtles etc.

Baylisascaris: Baylisascaris procyonis (raccoon), Baylisascaris columnaris (skunk), Baylisascaris laevis (woodchuck).

Gnathostoma: Gnathostoma spinigerum (dogs, cats and wild carnivores).

Streptopharagus: Streptopharagus species (primates).

Capillaria (respiratory sinus forms): Eucoleus bohmi, otherwise known as Capillaria bohmi (foxes).

Capillaria (intestinal form): Aonchotheca putorii (hedgehogs, raccoons, swine, bobcats, mustelids (stoats, weasels), bears).

Hymenolepis (tapeworm): Hymenolepis diminuta (rat, dog), Hymenolepis nana (rat).

Echinococcus (hydatid tapeworm): Echinococcus granulosis (coyote, wolf, dingo) and Echinococcus multilocularis (fox).

2. Wildlife protozoan parasites that may be diagnosed on fecal flotation:

Cryptosporidium (Cryptosporidiosis): Cryptosporidium species (common in many wild animal species), Cryptosporidium wrairi (guinea pigs). A small parasite, it can be difficult to find and recognise on a fecal flotation.

Giardia (Giardiasis): Giardia lamblia, Giardia muris (mouse), Giardia ranae (frog).

Balantidium coli (Balantidiasis): Balantidium coli (gorilla - can be disease-causing, rat - usually non-pathogenic, but can be zoonotic).

Coccidia (coccidiosis): Eimeria species (common in many wild animal species), Hammondia heydorni (fox, coyote, wild dog - non pathogenic).

1d) Human parasites that may be diagnosed on fecal flotation.

1. Human worm species that may be diagnosed on faecal egg flotation:

Typical 'roundworms': Ascaria lumbricoides.

Typical 'hookworms': Ancylostoma duodenale, Necator species.

'Tapeworms': Taenia saginata, Taenia solium, Dipylidium caninum.

Note - most Taenia and Dipylidium eggs exit the human host encased within a proglottid (tapeworm segment) and, consequently, free eggs will rarely be found in the person's faeces on a fecal float. Eggs that are released from

their proglottids into the faeces early may be detected on a fecal float.

Hymenolepis (tapeworm): Hymenolepis diminuta, Hymenolepis nana.

Strongyloides: Strongyloides fuelleborne.

2. Human protozoan parasites that may be diagnosed on fecal flotation:

Cryptosporidium (Cryptosporidiosis): Cryptosporidium parvum Type 1 (C. hominis), Cryptosporidium parvum Type 2. A small parasite, it can be difficult to find and recognise on a fecal float.

Giardia (Giardiasis): Giardia lamblia.

Balantidium coli (Balantidiasis): Balantidium coli (can be disease-causing).

Coccidia (coccidiosis): Sarcocystis hominis, Sarcocystis suihominis, Sarcocystis equicanis, Sarcocystis medusiformis (non-disease causing).

2) Limitations of fecal flotation - parasites it won't detect.

Not all parasites that affect our pets or livestock can be diagnosed using a fecal flotation test.

Parasites that do not dwell in the gastrointestinal tract, biliary ducts or lungs (where

the eggs may be coughed up and swallowed and appear in the faeces) will not be detected. Parasites whose eggs are too heavy to float (e.g. trematode eggs) or who exist solely

as motile, swimming protozoans (i.e. do not produce a resistant, floatable cyst) or who

reproduce by means of live larvae or quick-hatching eggs (live young, not floatable eggs) are also unlikely to be

detected by fecal flotation. Parasites who exert their tissue-damaging effects whilst still

in a larval or intermediate (juvenile) form will also fail to be diagnosed using this test

because these parasites have not yet attained enough maturity to produce eggs or oocysts that

will appear in the faeces. Tapeworms that shed whole segments into the faeces instead of individual eggs will also rarely be detected using

this fecal flotation test (they are actually easier to diagnose, however, because the segments are large and visibly obvious). Fragile parasites that are easily destroyed by most fecal floatation mediums will

also fail to be detected using this testing procedure.

The following lists provide examples of common parasites that can not be detected using simple

fecal flotation principles and the reasons why they can not be detected.

Parasites that do not live in the intestinal tract, biliary tract or lungs:

Parasites that live in the bloodstream and do not shed eggs or oocysts into the faeces: Trypanosoma, Babesia, Anaplasma, Leishmania, Theileria, Cytauxzoon felis, Malaria (Plasmodium), Haemoproteus, Leucocytozoon, Hepatozoon canis.

Parasites that live in the kidneys and shed their eggs and oocysts into the urine, not the faeces:

Klossiella equi (horse renal parasite), Klossiella muris (mouse kidney parasite), Schistosoma haematobium (human renal worm), Stephanurus dentatus (pig renal worm),

Dioctophyme renale, Capillaria plica (also called Pearsonema plica),

Trichosomoides (rat urinary parasite).

Parasites that live in the reproductive tract and do not shed eggs and oocysts into the faeces: Tritrichomonas foetus (cow protozoan parasite), Tritrichomonas vaginalis (human).

Other worm parasites that do not live in the gut, biliary tract or lung and which do not shed

eggs or larvae into the faeces: Rhabditis (skin worm), Dracunculus (worm that lives under the skin of humans and carnivores), Thelazia (eye worm), Dirofilaria immitis (heartworm),

Setaria (worms that affect the eyes and serous membranes of horses and cattle), Onchocerca cervicalis (adult worms that live in the nuchal (neck) ligaments of horses), Parafilaria (worms that live in the skin and muscle), Dipetalonema reconditum (worms that live

in the connective tissues of dogs), Capillaria hepaticum also called Calodium hepaticum (adult worm that lives in the liver and sheds eggs into the liver itself, not the biliary tract), Fascioloides magna (adult fluke is encased within cysts in the liver of atypical host animals - goats, sheep, cattle,

certain deer species and llamas - and sheds eggs into the liver tissues, not the biliary tract).

Parasites that enter the rectum and secrete eggs onto the edges of

the anus, not into the faeces: Oxyuris equi (equine pinworms), Enterobius (human and

ape pinworms).

Parasites whose eggs are too heavy to float:

Most of the following parasites are more readily diagnosed by fecal sedimentation (sediment) tests, not by fecal floatation tests, because their eggs tend to sink in flotation media.

Most Trematode (fluke or flatworm) eggs: Schistosoma mansoni (humans), Schistosoma japonicum (humans), Schistosoma bovis (cattle, sheep), Schistosoma indicum (horses, cows, goats, buffalo), Schistosoma suis (swine, dogs), Schistosoma matheei (sheep),

Heterobilharzia americana, Nanophyetus salmincola (a dog, cat and wild carnivore fluke which carries a dangerous Rickettsian organism that causes 'salmon poisoning' in pets), Paragonimus kellicotti (a lung fluke of cats and dogs and wild, fish-eating carnivores), Opisthorchis tenuicollis (dogs, cats, pigs, foxes and humans), Eurytrema procyonis (cats, raccoons), Platynosomum fastosum (cat),

Alaria (dogs and cats), Fasciolopsis buski (pigs, man), Fascioloides magna (white-tailed deer, man), Paramphistomum cervi (ruminants), Calicophoron calicophorum and Cotylophoron (flukes that lives in the rumen (stomach) of livestock animals), Dicrocoelium dendriticum (sheep, cattle, pigs, deer, rabbits, woodchucks, man), Gastrodiscoides hominis (fluke of monkeys and apes and man), Megalodiscus (frogs), Fasciola gigantica (man), Clonorchis sinensis (man), Fasciola hepatica (cows, sheep, goats, humans). The latter, Fasciola hepatica (liver

fluke), may sometimes be detected using sugar solution fecal flotation, however, the

eggs tend to distort a bit and more reliable detection is achieved using sedimentation techniques.

Certain Cestode (tapeworm) eggs: Anoplocephala in horses,

Diphyllobothrium latum, Spirometra mansonoides and Spirometra erinacei. Spirometra ('zipper worm') eggs can sometimes be detected on fecal flotation, however, the technique of choice for detecting the eggs of this tapeworm is faecal sedimentation.

Certain Acanthocephala (spiny-headed worms) eggs:

Macracanthorhynchus hirudinaceus (pigs), Macracanthorhynchus ingens (raccoons),

Prosthenorchis (monkeys).

Parasites who exist solely as fragile, motile, swimming protozoans (i.e. do not produce a resistant, floatable cyst):

Trichomonad organisms: Trichomonas, Tritrichomonas,

Monocercomonas, Histomonas in turkeys (no cyst is produced, but this organism is shed in the turkey's faeces hidden inside the eggs of a turkey worm: Heterakis gallinarum).

Amoebic Entamoeba organisms: Entamoeba histolytica

(usually non pathogenic in dogs and cats, but can cause severe disease in man), Entamoeba bovis (cattle)

and Entamoeba ovis (sheep).

Parasites who reproduce by means of live larvae or quickly-hatching eggs:

There are certain parasitic worm species that give birth to live young or that produce

eggs which hatch so rapidly, only live larvae are expelled in the animal's faeces. Although

live larvae may occasionally be detected on fecal flotation, what usually happens is

that the flotation solution warps them beyond recognition, making them impossible to identify

using this means. Living larvae are generally easier to detect using a Baermann test.

Worms that give birth to live young: Ollulanus (cat), Trichinella spiralis (pig).

Worms whose eggs hatch prior to fecal expulsion (larvae shed into stools):

Protostrongylus (lungworms of sheep and goats), Muellerius (lung worms of livestock),

Crenosoma vulpis (lungworms of wolves, foxes, raccoons, dogs), Aelurostrongylus abstrusus (feline lung worms), Angiostrongylus vasorum (dog lung), Filaroides hirthi and Filaroides osleri (canine lung worms), Strongyloides species of dogs, cats and people (S. stercoralis), Dictyocaulus (lungworms of livestock).

Worms whose entire life cycle is within the one host - no eggs shed into faeces:

Ollulanus (a worm that lives in the stomach of cats - adult worms produce live larval worms

which attach to the stomach wall of the same cat host and grow to adulthood there), Trichinella

(adult worms give birth to live larvae which migrate through the intestinal wall and encyst

within the muscles of the same host).

Parasites who exert their tissue-damaging effects whilst still

in a larval or juvenile (non-egg-producing) form:

There are hundreds of worm and protozoan species that exert their damaging effects on a host animal

prior to reaching full, egg-producing maturity. Damage may occur when juvenile worms

undergo their typical tissue-migratory phases (larval migrans) through their normal host

animals; damage may occur when atypical hosts become infected with injurious worm larvae (which

migrate and migrate, unable to complete their maturation into an adult stage in that host) and damage may also occur in the tissues of intermediate host animals when they become

infected with juvenile-stage worm and protozoan organisms as part of the parasite's normal

two-host, indirect life cycle. Such animals may become very ill as a result of this

parasitism, however, diagnosis will not be achieved using fecal flotation techniques

because the parasites are not yet mature.

Worms whose larvae exert damage during tissue migration:

hookworms, roundworms (e.g. Toxocara, Toxascaris), horse Strongyle larvae

in equine intestinal blood vessels, Baylisascaris (visceral and cutaneous larval migrans).

Worms whose larvae exert damage during tissue migration in atypical hosts:

Baylisascaris (visceral and cutaneous larval migrans), hookworms (cutaneous larval migrans), Parelaphostrongylus (parasite whose larvae affect the brains of sheep, goats, cows, horses, llamas, camels, moose, caribou, reindeer and other deer types), Echinococcus species (hydatid tapeworm cysts

in the organs and lungs of humans).

Parasites whose juvenile stages exert damage in intermediate hosts:

Sarcocystis species (e.g. S. neurona in the brain of cats and horses, S. cruzi in the liver, brain, blood vessels and muscles of cattle, S. tenella in sheep),

Toxoplasma gondii in humans and other intermediate hosts, Neospora caninum in the

muscles of dogs and reproductive organs of cows, Echinococcus species (hydatid tapeworm cysts

in the organs and lungs of livestock animals), Spirometra (larval tapeworms - 'spargana' - in the tissues of

wild reptiles, amphibians and other wildlife).

3) How is a fecal float performed? - a step-by-step pictorial guide.

Step 1: Collect the faeces.

The best stool samples to get are those that are fresh - straight out of the animal within the last 30 minutes where possible. Attempting to perform a fecal float on a stool sample that is several days old is likely to be unhelpful because most of the eggs, worm larvae and protozoan oocysts will have altered in appearance

to the point of being unrecognizable. Some worm eggs hatch within hours of defecation

and, consequently, will not be visible in the fecal float, resulting in a false negative result.

Can you float diarrhoea?

The answer is yes. Dogs and cats do not have to be producing solid

feces in order for a fecal float to be performed - faecal floats can be performed on the most

watery or slimy or bloody of faeces. The image below (image 1) shows a dog 'straining to defecate' and producing mucoid, slimy, blood-filled faeces (this particular dog was actually producing the horrendous, bloody, slime-filled diarrhea seen in image 4). This watery, gelatinous diarrhoea is ideal for 'floating'.

Image 1:

Image 1: A dog with colitis passing bloody, mucus-filled faeces.

Image 2:

Image 2: A normal-looking stool sample can undergo fecal flotation. Such droppings may contain

tell-tale worm eggs or protozoan oocysts, despite looking relatively unremarkable.

Image 3: A fairly typical example of the kind of stools produced by a dog with colitis

(inflammation of the large intestine and rectum). Colitis stools themselves range from being watery, right through to a lumpy, custard-like consistency. These faeces are typically coated with or released alongside large volumes of yellowish, jelly-like slime (mucus).

Variable amounts of fresh, red blood may also be present (colitis stools may contain no blood, small flecks of blood or heaps of blood, depending on the case). Many types of parasites and infectious diseases, including:

Giardia,

Clostridium,

Yersinia, Campylobacter, coccidia and whipworms can produce these kinds of faeces. A fecal float would be an essential part of the work-up for a dog or cat that presented with these kinds of feces.

Image 4: An example of severe colitis - these stools are very watery and contain

loads of slime and mucus (the white flecks amidst the red blood) and lots of fresh, bright red blood. This particular dog had hemorrhagic gastroenteritis caused by Clostridial

overgrowth (a bacterial infection of the colon that normally occurs secondary to acute diet change

or dietary intolerance), however, it could easily have had a protozoan or whipworm infection that might have been picked up on fecal flotation. You can't make a diagnosis just by looking at the gross appearance of the feces - diagnostic testing is required.

The FECALYZER (fecal flotation test kit).

The in-house fecal flotation 'Fecalyzer' (also spelled Fecalyser) apparatus, used by many veterinarians, consists of an outer casing (the white plastic capsule or outer casing) containing a green fecal

filtration 'basket'. Image 5 shows the 'Fecalyzer' test kit with the green filtration basket and the white outer casing separated. Pictures 6 and 7 display how they appear when they are assembled correctly.

Image 5: Fecalyzer apparatus with the white outer casing and green filtration basket separate.

Image 6 and 7: Fecalyzer apparatus appearance when assembled correctly.

Step 2: Remove the green filtration basket from the Fecalyzer and place a sample of

faeces into the bottom of the white casing.

The faecal sample is initially placed into the bottom of the white case without the

green filtration basket in place. We want the feces underneath the filtration basket

and not on top of it because the purpose of the filtration basket is to allow the

small fecal particles and parasite eggs/oocysts to float upwards (they pass through the small mesh holes in the basket), whilst barring the way for the much larger chunks of fecal matter that might obscure the visibility of the parasite eggs and oocysts.

Any amount of fecal material can be floated (even small samples), but better results are expected with larger samples of feces (a fecal sample about the size of a medium to large marble is ideal).

Step 3: Replace the green filtration basket into the white case of the Fecalyzer.

The filtration basket's base will squish the feces as it is returned into its correct place.

Step 4: Half-fill the white case with flotation medium (fecal flotation solution).

A solution of sodium nitrate, Sheather's sugar solution, zinc sulfate solution, sodium chloride solution

or potassium iodide solution is added to the faeces within the Fecalyser (see section 7 for info

on the best fecal flotation solutions to use). The solution is poured in until it reaches 1/2 to 2/3rds of the way up the white casing (there is actually an arrow marked on the side of the white plastic casing that indicates how much solution to pour in initially). Once the flotation medium

is in place, the filtration basket is then rotated vigorously back and forth about its base (within the white casing). This action breaks up the fecal material into fine particles

that become suspended throughout the fecal flotation solution.

The purpose of the fecal flotation solution is to 'float' the parasite eggs and oocysts whilst

leaving the heavier faecal materials behind on the bottom of the container. It works on

the principles of buoyancy. The eggs and oocysts are less dense (lighter) than the fecal flotation solution and, consequently, they float on the very surface of it. The

feces themselves are more dense (heavier) than the fecal float solution and, as a result, they sink to the bottom of the solution, out of the way.

Image 8: One of the more commonly used fecal flotation solutions - sodium nitrate.

Image 9: An image of what is seen following the completion of step 4 - the white casing is half-filled with sodium nitrate solution and the feces have been churned up and suspended throughout the solution by vigorous turning of the green filtration basket.

Step 5: Press down on the green filtration basket until it is locked into place.

Following step 4, where the basket was twisted back and forth about its base in order to agitate and suspend the feces, the green basket is no longer required to be mobile.

In fact, the filtration basket must be positioned firmly in place if steps 6-onwards are to work.

By pressing the green filtration basket downwards firmly, the basket will lock into place within the white casing and no longer move.

Step 6: Fill the Fecalyzer completely with the fecal flotation solution, forming a raised meniscus..

The fecal flotation solution is poured carefully into the Fecalyzer apparatus, filling it

all the way to the top. Once the fluid level reaches the top of the green basket, a tiny

bit more solution is added, such that the fluid line pokes out above the top of the basket

but is unable to spill over the edges. This raised, curved bulge of fluid is termed a meniscus.

Images 10 and 11: Pictures of the meniscus.

Step 7: Place a glass microscope coverslip over the meniscus and leave it in place for 10 minutes.

A glass coverslip is placed gently on top of the meniscus. It is left in place for 10 minutes if the flotation solution used is sodium nitrate solution - the most common solution used.

If Sheather's sugar solution is used as the flotation medium, 20 minutes are required because of this solution's high viscosity. Time is required for the parasite eggs and oocysts to drift upwards, through the fine fecal suspension, to the surface of the fluid. These eggs and oocysts collect at the surface of the fluid layer, adjacent to the

microscope coverslip glass. These eggs and oocysts will be picked up, along with a thin layer of fluid,

when the coverslip is removed from the Fecalyzer at the end of the time period.

Image 12 and 13: Pictures of the microscope coverslip sitting on top of the meniscus. The microscope

coverslip has been outlined in image 13 to make it more clearly visible in the photo.

Step 8: Place the coverslip, wet-side-down, onto a clean, glass microscope slide.

The coverslip is placed, wet-side-down, onto a glass microscope slide, sandwiching the fecal flotation fluid and any parasite eggs or oocysts between the glass coverslip and the glass

slide.

Image 14: The glass coverslip (containing fecal float solution and, hopefully, parasite eggs/oocysts)

is placed on top of the glass microscope slide.

Step 9: Examine slide under microscope.

The slide is examined carefully and systematically for any presence of parasitic organisms

(eggs, oocysts and worm larvae). The microscope slide is normally examined at very low powers initially (40x, 100x and 400x magnifications) - many worm eggs and even some of the larger protozoan oocysts (e.g. Isospora cysts - see image 16) can be clearly seen at lower powers. If this low power examination yields little (or even if

something is found), the veterinarian or pathologist then examines the slide under

high power oil immersion (1000x - extreme close-up magnification). Very small organisms may only be visible under extremely high magnifications.

Image 15: Image of a microscope with a faecal float slide in place.

Examples of things that might be seen under the microscope:

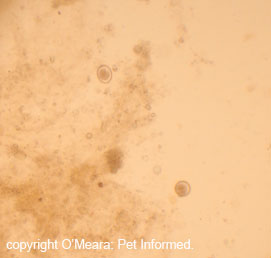

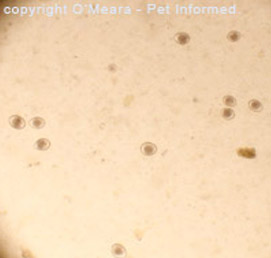

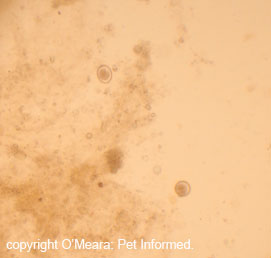

Image 16: Two Isospora canis (coccidia) oocysts seen at low power.

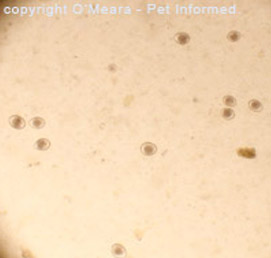

Image 17: Isospora felis oocysts seen at low power - these cysts are more pointed than the canine form of coccidia.

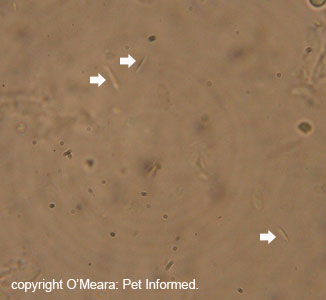

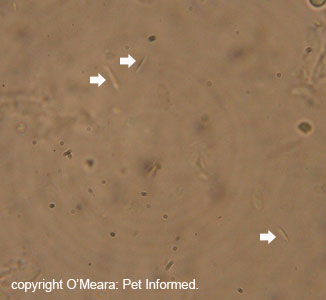

Image 18: Bacterial rods (indicated with white arrows) seen at 400x.

Image 19: Extreme close-up (1000x) of bacterial rods seen in a fecal floatation sample. These may or may not be clinically significant - bacteria are

normally seen on fecal floats.

Image 20: Isospora oocyst (extreme close-up - 1000x) prior to any maturation.

Image 21: Isospora oocyst (extreme close-up - 1000x) starting to undergo maturation

to its infectious state (see coccidia page for more details on coccidiosis). See how

the organism now has two central balls of cells, instead of just the one (as seen in image 20)?

It has undergone its first lot of cell division and maturation.

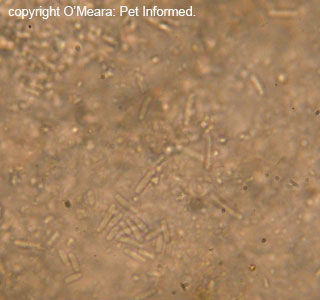

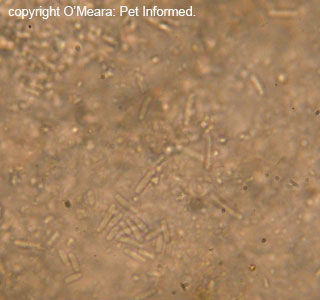

Image 22: Close-up image of an Isospora felis oocyst seen in a fecal flotation. The tiny rod-shaped

lines surrounding the oocyst are bacteria. This image gives you an idea of the relative

size differences between bacterial and protozoan coccidia organisms.

NEW! - Visit our great Fecal Float Parasite Pictures Gallery!

Cool case study: Here's a cool example of how fecal flotation testing can be put to practical use:

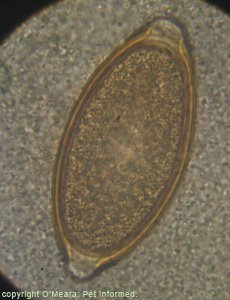

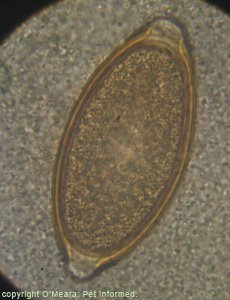

The following eggs were discovered on a recent fecal flotation of a kitten's faeces

at our clinic.

Image 24: This is a high-power (1000x oil immersion) view of one of the eggs - a Spirometra tapeworm egg.

Image 25: This is another high-power (1000x oil immersion) image of one of the fecal float eggs - a Spirometra tapeworm egg.

The kitten was wormed with an all-wormer tablet, one that included a common tapeworming medication: Praziquantel.

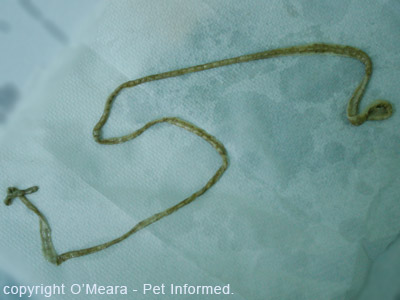

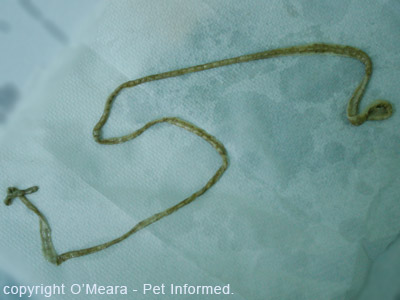

Within the day, a large (60cm) Spirometra tapeworm (also commonly known as a 'zipper-worm')

was voided in the kitten's faeces.

Image 26: This is the large Spirometra tapeworm that was voided in the kitten's faeces.

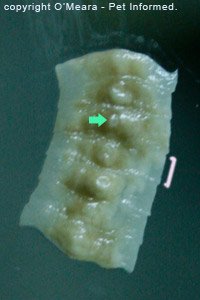

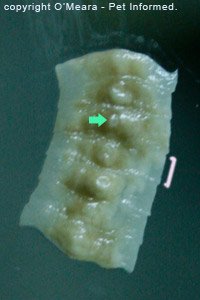

Image 27: This is a close-up of 7 of the tapeworm's proglottid segments (a single segment is indicated with a pink bracket).

The green arrow indicates the pore (hole) through which the tapeworm segment voids its eggs.

Cool case study 2. Here's another excellent example of how fecal flotation testing can be put to practical use:

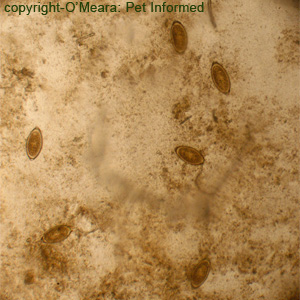

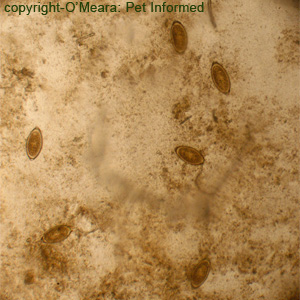

The following eggs were discovered during a fecal flotation test of a wolfhound pup's faeces. The dog presented

with severe, watery, slimy diarrhoea and signs of colitis.

Image 28: This is a low-power view of the fecal float slide showing several 'elongated-lemon shaped' eggs - whipworm eggs.

Image 29: This is a high-power (1000x oil immersion) view of one of the eggs - a Whipworm or Trichuris vulpis egg.

The puppy was wormed with an all-wormer tablet. Overnight, several small Trichuris whipworm adults

were voided in the puppy's faeces.

Image 30: This is an image of three adult whipworms which were voided in the puppy's feces. Two of them show the distinctive whip-like tail of the worm.

Image 31: This is a close-up of one of the adult whipworms which were voided in the puppy's feces. The distinctive whip-like tail of the worm is clearly visible.

Image 32: This is an image of the three adult whip worms (Trichuris) when compared to the size of a 10-cent piece. The worms are tiny!

NEW! - Visit our great Fecal Float Parasite Pictures Gallery!

4) Collecting and storing stool samples for your vet to test using a fecal floatation.

How fresh do stool samples need to be?

As a general rule, the best stool samples to perform a fecal flotation on are those that

are as fresh and as recent as possible (i.e. straight out of the dog or cat). Ideally, feces

should be tested within 30 minutes of leaving an animal. The reason we want an extra fresh stool sample is because the eggs of some parasites (e.g. parasite worms) hatch very rapidly, making these particular parasites impossible to diagnose on aged stool samples. A fresh sample makes these parasites easier to detect.

Your veterinarian will often collect an extra-fresh stool sample from your dog or cat's anus during the consult, using a gloved finger, or collect samples of the faeces that your dog or cat passes in the consultation

room or cat carrier. Alternatively, you, as the owner, can help your vet to get a diagnosis by

bringing your pet's most recent stool sample (e.g. diarrhea sample) into the consultation for flotation.

What volume of faeces is required for successful testing?

You can never bring too many stools in for sampling. The more stools there are, the

more chance a vet has of finding parasites in them - this is particularly the case with

parasites that only shed few eggs or parasites whose eggs are not evenly distributed throughout the host animal's droppings. As a general guide, a minimum of 5-10 grams

of faeces (about the size of a large marble) needs to be submitted for best fecal floating results.

With watery faeces (diarrhoea), you should bring in as much as possible, scooped into a

clean jar or fecal sample pot.

How can I (the owner of the pet) collect a fecal sample at home?

It can often be very helpful to your veterinarian if you, the owner of the pet, collect

the most recent sample of your pet's abnormal faeces (e.g. slimy stools, diarrhoea etc.)

and bring them into the clinic with you when you go in for a consultation. Not only can

these home-collected faeces be floated, should your vet fail to successfully collect an extra-fresh stool sample

in the consultation room, but letting the vet see the faeces gives him or her some insight

into what you, as the owner, are seeing your pet do at home. It is not unusual for pet symptoms to become miraculously normal in the vet clinic - bringing abnormal stools with you

will provide evidence of the nature of your pet's illness.

Fecal samples should be submitted in small, preferably sterile, air-tight containers such as fecal

sample jars or urine specimen pots, with the lid screwed tightly into place. Your vet can provide you with an appropriate specimen container to collect your pet's faeces into. At a pinch, you can use a new, ziplocked, sandwich bag for carrying samples of faeces into the veterinary clinic - just make sure you double-bag the sample so that it does not leak. I would advise against placing excessively watery diarrhoea into sandwich bags,

however, as these invariably leak and make a foul mess. Do not place faecal samples into old

jam jars - even when cleaned these often contain fungi that can confuse the diagnosis.

People should always wear disposable gloves when collecting faeces or vomitus from any

animal. It is possible to catch a number of fecally-transmitted diseases from your pet.

How can I store faecal samples at home, if they are produced after-hours?

Faecal samples should be taken into the vet clinic for testing as soon as they are collected (within 30 minutes ideally), however, if the stool sample is collected after-hours, you can place the well-sealed fecal sample into your fridge for safe storage. Chilling the stool sample slows the development and hatching of any worm eggs and keeps the sample

fresh. Do not put samples in the freezer - freezing destroys the eggs and oocysts.

It is possible to add preservatives such as 10% formalin, potassium dichromate or PVA (polyvinyl alcohol) to fresh faeces - these preservatives 'fix' and preserve

any worm eggs, larvae and protozoan organisms in their current, fresh state, allowing faeces to be stored long-term and tested later. Because these substances are all highly toxic

and potentially carcinogenic (cancer-causing), however, preserving pet faeces is

probably not a realistic or safe option for the average human owner. Chemists, medicos and skilled lab technicians may be able to make use of this technique, however,

as a general rule, I would not recommend that people attempt to preserve their pet's faeces in the home. I have just added this point in for completeness.

Do I need a consultation or can I just drop abnormal fecal samples in to my vet clinic for testing?

Normal and abnormal stool samples can just be 'dropped off' at veterinary clinics for fecal flotation, should pet owners be concerned about parasites in their pets. Although it is always recommended that owner and pet do go into the clinic for a proper consultation and examination, busy owners on their way to work or owners unable to get a vet appointment until later may attempt to get a more rapid diagnosis by dropping off samples of normal-looking; slimy, blood-tinged or diarrhoeic faeces for testing.

What are the problems of at-home faecal collection?

There are two major problems that I can see with at-home collection of stool samples:

1) The age of the faeces: As mentioned previously, faecal samples should, ideally, be tested within 30 minutes of being voided from

the animal. After this time, certain worm eggs start to hatch and become unrecognisable

on fecal floats and living worm larvae and free-living protozoan organisms start to die off or migrate away from the stool samples (e.g. onto the lawn or into the soil),

making them undetectable.

2) Human health risks: It is possible for certain fecally-shed bacterial, worm and protozoan parasites to infect humans and to cause symptoms of disease, even death, in human hosts.

Well-known examples of pet parasites that can directly infect humans following contact with pet faeces include: Baylisascaris, Toxocara (roundworms), Echinococcus (hydatid tapeworms), Balantidium coli, Toxoplasma (Toxoplasmosis), Escherichia

coli (E. coli), Salmonella and Campylobacter. Humans collecting and/or cleaning up animal faeces within the home need to adopt very good hygiene practices (wearing disposable gloves when collecting and cleaning faeces, thoroughly washing hands afterwards etc.) so that they do not inadvertently catch

fecal-borne pet parasites.

People who should not collect or come into contact with pet faeces in the home:

There are certain fecally-transmitted pet parasites and bacteria that may be life-threatening or even fatal to humans. As a general rule, most humans that come into contact with these pet parasites and bacteria will show no symptoms of infection because their immune systems are fully-operational and able to destroy the invading organisms.

People who are unable to mobilize an effective immune system response towards

invading organisms (e.g. fetuses, people with immune-suppressive conditions) are at greater

risk of showing severe disease symptoms should they contract a parasite or infectious

disease organism from a pet's faeces. The following people (listed) should never expose themselves to the disease risks associated with collecting pet faeces - they should

leave the task to their veterinarian or a family member.

People with the following conditions should never handle or come into contact with pet faeces:

Pregnant owners, particularly cat owners.

Immunosuppressed patients (e.g. people with HIV or AIDs or bone marrow diseases).

People on chemotherapy and other immune suppressing drugs.

People with permanent, indwelling catheters in place (e.g. kidney dialysis catheters, colostomy bags, intravenous lines).

Small children (especially babies and toddlers).

5) False positive fecal flotation results (when is a 'significant' result not really significant?).

It is possible for parasite eggs and oocysts to be found on fecal flotation and for

parasitism not to be the animal's main disease process. Such positive test results are termed false positive results and they occur for several reasons:

1) The animal is a non-clinical carrier of the parasite:

Many parasitic worms and protozoan organisms can exist within a host animal's intestinal tract, lungs

or biliary ducts without producing any obvious symptoms of disease within that animal. This state of

asymptomatic parasitism, termed a carrier state, can occur for many reasons, the most common being:

a) The animal is only carrying a low number of parasites within its body (e.g. a single tapeworm), nowhere

near enough to cause disease signs.

b) The animal host's immune system has successfully suppressed the aggressive, rapid replication of the parasites (e.g. protozoans), but been unable to clear (remove) them

from the host's body completely, resulting in persistent, non-symptomatic parasitism.

Because even very low numbers of worm and protozoan parasites can shed eggs and oocysts into

the host animal's faeces, these low-grade, asymptomatic parasite infestations can

often be detected on faecal floatation tests. Vets that detect these eggs and oocysts

and fail to realise that they are looking at a non-clinical, incidental parasite infestation may over-interpret the significance of the parasite finding (i.e. a false positive test result). They may then, incorrectly, attribute any gastrointestinal or respiratory tract symptoms

in that host animal as being a result of the parasitism when, in fact, symptoms seen are being caused by some other disease process entirely. This misdiagnosis becomes potentially

dangerous for the animal patient when the vet starts treating it for the parasitism

and not for its actual disease! In such false positive cases, treatment directed at the parasite is unlikely to resolve the symptoms of disease in the host animal

because the primary disease has not been diagnosed or treated.

2) The animal has clinical parasitism due to an underlying immune disorder:

This is kind of a true positive/false positive combination situation. Carrier animals with certain parasites in their intestines (e.g. coccidia, Entamoeba) can sometimes revert back to clinical signs of parasitism if their immune system control over the organisms in their bodies fails. This immune suppression may occur as a result

of stress or a range of other congenital and acquired immune deficiencies. Although

finding eggs or oocysts in the faeces of these animals is proof of the parasitic infectious disease causing the symptoms (a true positive), it can also be considered to be a false positive if the underlying immune disorder or stressor, which is causing the organism to become a problem, is not diagnosed and managed too.

3) The parasite species found on fecal flotation is not the right species for that host:

As can probably be inferred from the animal and parasite species lists seen in section

1, many species of parasite (especially protozoa) are highly discerning and specific about which species of animals they will and will not actively infest. Dogs and cats (and other animals) that consume the droppings of another animal species will often inadvertently

consume worm eggs and protozoan oocysts contained in these faeces. If these ingested eggs

and oocysts are not able infest that dog or cat host, due to species incompatibility, these eggs and oocysts will not hatch and will, instead, travel, unchanged, throughout the dog or cat's intestine and be shed into its faeces. Vets that float these faeces, find these

eggs and/or oocysts and fail to recognise that they belong to a non-dog or non-cat species

of parasite will often incorrectly diagnose these animals as being positive for the parasitic disease.

4) Some species of parasites are incidental and simply not pathological:

It can be very easy, as a veterinarian, to get extremely excited when worm eggs or protozoan

oocysts are spotted on a faecal float. We love to think that any organisms seen are

diagnostic: sure proof of the reason for an animal's symptoms. It must not be forgotten,

however, that, spectacular as they may look under the microscope, some parasites can live within an animal and cause absolutely no symptoms at all simply because they are not disease-causing organisms. Worms like Capillaria and protozoans like Hammondia, Besnoitia and intestinal Sarcocystis do not cause disease symptoms in animals and,

consequently, finding these organisms in a fecal float does not provide the vet with any

deeper clue as to the reasons for an animal's clinical symptoms.

5) Lab error and veterinarian inexperience:

Lots of weird objects can be found in fecal floats: anything from bubbles to pollen balls to fungal hyphae. It is possible for inexperienced vets to incorrectly identify these objects as parasite eggs or oocysts and to, consequently, falsely determine the animal to be positive for a parasitic disease.

6) Incorrectly diagnosing the correct parasite species:

This is a combination false positive and false negative situation. A lot of parasitic worm eggs and larvae look similar to each other, as do a number of protozoan

oocysts. A classical example is Capillaria and Trichuris (whipworm) eggs - these eggs look almost identical to each other. It is easy for veterinarians to incorrectly

diagnose an animal as being positive for one particular parasite when it is, in fact, positive for a different organism with a similar-looking egg or oocyst. The parasite species

incorrectly diagnosed is a false positive result and the parasite species left undiagnosed, as a result

of this misidentification, is a false negative result. This misidentification

may have implications for the diagnosis and explanation of an animal's clinical

signs: for example, a diagnosis of whipworm would explain an animal's symptoms of colitis, however, if the parasite eggs found were actually Capillaria eggs (non-disease-causing), then any colitis symptoms seen would be unlikely to have anything to do with this parasite finding.

6) False negative fecal float results (when a 'negative' test result is not truly negative).

It is possible for an animal to truly have parasitism, but for tell-tale eggs, larvae and/or oocysts not to be discovered on a fecal floatation test. These test results are termed false negative test

results and they occur for several reasons:

1) Certain parasite eggs and oocysts may be shed intermittently:

Many species of intestinal protozoa, including Isospora, many other coccidians and Giardia, are well known for having a cyclic pattern of protozoan replication and oocyst production. These organisms tend to release oocysts into the animal's faeces in waves. The consequence of this is that some stool samples will contain loads of oocysts and other stool samples, from the same animal, will show almost none. The veterinarian who happens to be unlucky enough to get the stool sample without the organisms will come up with a negative result (a false negative)

when other stool samples from the same animal might be full of the tell-tale oocysts. As an added twist to the tale, some species of parasites (e.g. Toxoplasma in cats)

only shed for a brief period of time (e.g. 2 weeks for Toxoplasma), never to be shed into

the faeces again. This provides the vet with only the briefest window of time for making

a positive diagnosis of the disease based on a fecal float.

2) Some worms and protozoans only shed very low numbers of eggs or oocysts:

It is possible for an animal to have clinical signs of parasitism and to only be shedding low numbers of eggs or oocysts into the faeces. Eggs and oocyst numbers are not always a reliable indicator of whether the animal is clinically infected with a parasite or not. Obviously, large numbers of parasitic eggs or

oocysts are more supportive of clinical infection, however, low numbers of eggs or oocysts

may be all that are seen in some animals as an indicator of active infection. Because

fecal floatation is performed using a human eye, it is possible for very small numbers of eggs or oocysts to be missed if the vet isn't careful and observant, thereby resulting in a false negative result.

3) Low parasite burdens in the host animal:

Similar to point 2 (above), low numbers of parasites will generally shed lower numbers

of eggs or oocysts into the animal's faeces. Low numbers of parasites can, however, sometimes produce significant symptoms of disease in an animal or pose significant

risk to human pet owners (e.g. Echinococcus), despite their small populations. Because fecal floatation is performed using a human eye, it is possible for very small numbers of eggs or oocysts to be missed if the vet isn't careful and observant, thereby resulting in a false negative result.

4) Lab error and veterinarian inexperience:

Faecal float examination is a skill acquired with years of practice. It is possible for inexperienced practitioners not to recognise and identify parasitic oocysts and eggs and to make a false negative diagnosis.

5) Destruction of the parasitic eggs or oocysts by the fecal float solution:

Some of the solutions used in the fecal flotation process (e.g. sodium nitrate and sometimes even Sheather's Sugar solution) can distort or destroy the larvae, eggs or oocysts in the fecal sample, resulting in false negative results. Which eggs and oocysts

get destroyed has as much to do with the innate fragility of the parasites themselves as with the characteristics of the floatation medium. Some resistant ova (e.g. coccidia oocysts)

will survive any medium, whereas other, more fragile ova (e.g. Giardia cysts) may be easily

destroyed. Zinc sulfate solution is thought to distort and destroy oocysts, eggs and larvae the least of any of the flotation mediums (resulting in fewer false negative results)

and is the medium of choice for Giardia and Balantidium. Sheather's sugar solution is preferred for coccidia detection, but will distort Giardia oocysts beyond recognition.

6) Certain parasite eggs do not float very well:

Certain 'heavy' parasite eggs (e.g. whipworm, Capillaria and trematode eggs) do not

float well in the most-commonly-used fecal floatation solution: sodium nitrate. This can result in false negative results (eggs that don't float can't be detected). Different flotation solutions (e.g. potassium iodide) may be required to diagnose these

heavy eggs (see section 7 on best fecal float solutions).

7) Some eggs hatch very early, making worm infestations hard to detect:

The eggs of certain worms (e.g. many lungworm species and some intestinal worm species)

develop and hatch extremely rapidly, sometimes hatching even before the faeces have left the host animal. Hatched eggs are broken in appearance and impossible to diagnose on fecal flotation. Aside from a few slow-moving exceptions (e.g. Filaroides larvae), most hatched worm larvae are highly motile or do not float very well, making them hard to

detect on routine fecal floatation. This results in many false negative fecal floats.

8) Old faecal samples:

The older the fecal sample (beyond 30 minutes of leaving the animal), the more chance there is

of getting a false negative result. Fragile oocysts start to degenerate and break down, worm eggs start to hatch and motile worm larvae start to leave the droppings (they migrate out of the droppings onto the lawn and soil). All of these things make parasitic

eggs, larvae and oocysts more and more difficult to detect and increase the likelihood of

a false negative result.

9) Some parasite organisms produce severe signs before the eggs or oocysts actually appear in the poo:

It can take some time (e.g. up to 15 days for coccidia), from the time of initial host infection, before fecally-shed eggs or oocysts will begin to appear in a host animal's faeces, in order to be detected by a fecal float. Within this time, severe clinical

symptoms of parasitism can occur (depending on the parasite species involved), without there being any eggs or oocysts visible in the droppings.

10) Incorrectly diagnosing the correct parasite species:

This is a combination false positive and false negative situation. A lot of parasitic worm eggs and larvae look similar to each other, as do a number of protozoan

oocysts. A classical example is Capillaria and Trichuris (whipworm) eggs - these eggs look almost identical to each other. It is easy for veterinarians to incorrectly

diagnose an animal as being positive for one particular parasite when it is, in fact, positive for a different organism with a similar-looking egg or oocyst. The parasite species

incorrectly diagnosed is a false positive result and the parasite species left undiagnosed, as a result

of this misidentification, is a false negative result. This misidentification

may have implications for the diagnosis and explanation of an animal's clinical

signs: for example, a diagnosis of whipworm would explain an animal's symptoms of colitis, however, if the parasite eggs found were actually Capillaria eggs (non-disease-causing), then any colitis symptoms seen would be unlikely to have anything to do with this parasite finding.

7) A short guide to the best fecal flotation solutions for diagnosing various parasites.

The following information is a guide to the better fecal flotation solutions available for

successfully floating and diagnosing our more common pet parasites. Not every single parasite is listed, only those I could find references for, however, you should be able to find most

of the more common pet and livestock worm and protozoan infestations listed here. For ease of reference, I have listed the parasites in alphabetical order.

Author's note: routine fecal floats are normally performed in veterinary clinics using sodium nitrate solution (domestic pets or livestock), sodium chloride solution

(livestock) or, sometimes, zinc sulfate solution. Specialized, high specific gravity

solutions such as potassium iodide are not normally used for routine fecal floats

unless the vet has a strong suspicion that a specific parasite (e.g. whipworm, fluke)

is to blame.

Protozoans:

Balantidium coli - zinc sulfate fecal flotation solution is best.

Besnoitia species - often found in sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution, but Sheather's Sugar solution is best.

Cryptosporidium parvum - saturated sucrose solution is best.

Eimeria species - often found in sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution, but Sheather's Sugar solution is best.

Giardia lamblia (G. duodenalis) - zinc sulfate solution is best. Distorts in Sheather's Sugar.

Hammondia species - often found in sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution, but Sheather's Sugar solution is best.

Isospora species - often found in sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution, but Sheather's Sugar solution is best.

Neospora caninum - Sheather's Sugar solution is best.

Sarcocystis species - often found in sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution, but Sheather's Sugar solution is best.

Toxoplasma gondii - Sheather's Sugar solution is best.

Worms and flukes:

Ascaridia species - sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Ascaris suum - sodium chloride or zinc sulfate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Bunostomum species (hookworms) - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Capillaria species - high SG solution is best (e.g. potassium iodide at 50% saturation).

Chabertia ovina - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Cooperia species - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Fasciola hepatica (liver fluke) - fecal sedimentation test is best, but may float in Sheather's Sugar solution

or other high specific gravity solutions.

Filaroides hirthi larvae (dog) - these fecally-shed worm larvae are relatively 'immobile' and do not readily migrate away from the animal's faeces. They

can sometimes be detected on fecal flotation, especially zinc sulfate flotation.

Globocephalus species (hookworms) - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Gnathostoma species - sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine. Sodium chloride or zinc sulfate is fine

when hunting for Gnathostoma species in pigs.

Habronema species - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Haemonchus contortus (barber's pole worm) - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Heterakis: species - sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Macracanthorhynchus species - generally these eggs float poorly, however, they may occasionally be detected using sodium chloride or zinc sulfate fecal flotation media.

Metastrongylus species - sodium chloride or zinc sulfate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Moniezia species - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Nematodirus species - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Oesophagostomum: - species - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Ostertagia ostertagi - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Paramphistomes (rumen flukes) - fecal sedimentation test is best, but may float in Sheather's Sugar solution

or other high specific gravity solutions.

Parascaris equorum - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal floatation solution is fine.

Physocephalus species - sodium chloride or zinc sulfate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Spirocerca species - sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Spirometra species - sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Strongyloides species - sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Strongylus species - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate is fine.

Teladorsagia species - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Thysaniezia species - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Trematodes - some trematode eggs will float in potassium iodide solution (very high specific gravity),

however, fecal sedimentation is the usual test employed for diagnosing these organisms.

Trichostrongylus species - sodium chloride or sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Trichuris species (whipworm) - high SG (specific gravity) fecal flotation solution is best (e.g. potassium iodide at 50% saturation).

Typical 'hookworms': Ancylostoma species, Uncinaria stenocephala - sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

Typical 'roundworms': Toxocara species, Toxascaris leonina - sodium nitrate fecal flotation solution is fine.

To go from this fecal flotation page to the Pet Informed home page, click here.

NEW! - Visit our great Fecal Float Parasite Pictures Gallery!

Fecal Flotation References and Suggested Readings:

1) Dubey JP, Greene CE,Enteric Coccidiosis. In Greene CE, editor: Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, St. Louis, 2006, Saunders Elsevier.

2) Little SE, Laboratory Diagnosis of Protozoal Infections. In Greene CE, editor: Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, St. Louis, 2006, Saunders Elsevier.

3) Baneth G, Hepatozoonosis. In Greene CE, editor: Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, St. Louis, 2006, Saunders Elsevier.

4) Barr SC, Enteric Protozoal Infections. In Greene CE, editor: Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, St. Louis, 2006, Saunders Elsevier.

5) Dubey JP, Lappin MR Toxoplasmosis and Neosporosis. In Greene CE, editor: Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, St. Louis, 2006, Saunders Elsevier.

6) Barr SC, Cryptosporidiosis and Cyclosporiasis. In Greene CE, editor: Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, St. Louis, 2006, Saunders Elsevier.

7) Host-Parasite Relationships. In Carter GR, Chengappa MM, Roberts AW editors: Essentials of Veterinary Microbiology, USA, 1995, Williams and Wilkins.

8) Sources and Transmission of Infectious Agents. In Carter GR, Chengappa MM, Roberts AW editors: Essentials of Veterinary Microbiology, USA, 1995, Williams and Wilkins.

9) Protozoans. In Bowman DD, Lynn RC, Eberhard ML editors: Parasitology for Veterinarians, USA, 2003, Elsevier Science.

10) Helminths. In Bowman DD, Lynn RC, Eberhard ML editors: Parasitology for Veterinarians, USA, 2003, Elsevier Science.

11) Diagnostic Parasitology. In Bowman DD, Lynn RC, Eberhard ML editors: Parasitology for Veterinarians, USA, 2003, Elsevier Science.

12) Rose K, Common Diseases of Urban Wildlife. In Wildlife in Australia: Healthcare and Management - PGF Proceedings 327, Sydney, 1999, Post Graduate Foundation in Veterinary Science.

13) Blyde D, Advances in Treating Diseases of Macropods. In Wildlife in Australia: Healthcare and Management - PGF Proceedings 327, Sydney, 1999, Post Graduate Foundation in Veterinary Science.

14) Lappin MR, Protozoal and Miscellaneous Infections. In Ettinger SJ, Feldman EC, editors: Textbook of Veterinary

Internal Medicine, Sydney, 2000, WB Saunders Company.

15) Phylum Platyhelminthes. In Hobbs RP, Thompson ARC, Lymbery AJ: Parasitology, Perth, 1999, Murdoch University.

16) Phylum Nemathelminthes. In Hobbs RP, Thompson ARC, Lymbery AJ: Parasitology, Perth, 1999, Murdoch University.

17) Subkingdom Protozoa. In Hobbs RP, Thompson ARC, Lymbery AJ: Parasitology, Perth, 1999, Murdoch University.

18) Diagnostic Techniques. In Hobbs RP, Thompson ARC, Lymbery AJ: Parasitology, Perth, 1999, Murdoch University.

Pet Informed is not in any way affiliated with any of the companies whose fecal flotation products

appear in images or information contained within this article. The images, taken by Pet Informed, are only used in order to illustrate certain points being made in the article.

Copyright June 5, 2008, www.pet-informed-veterinary-advice-online.com.

All rights reserved, protected under Australian copyright. No images or graphics on this Pet Informed website may be used without written permission of their owner, Dr. O'Meara.

The fecal flotation apparatus: Fecalyzer is a registered trademark of Vetoquinol.

A fecal flotation test, otherwise known as a 'fecal float', egg flotation or Fecalyzer Test (Fecalyzer, also spelled Fecalyser, being the most commonly used in-house commercial product) is a diagnostic test commonly performed in-house in most veterinary clinics as a way of diagnosing parasitism in animals. This page includes everything you, as a pet owner, might want to know about the fecal flotation tests performed by your veterinarian on your pet's stools:

A fecal flotation test, otherwise known as a 'fecal float', egg flotation or Fecalyzer Test (Fecalyzer, also spelled Fecalyser, being the most commonly used in-house commercial product) is a diagnostic test commonly performed in-house in most veterinary clinics as a way of diagnosing parasitism in animals. This page includes everything you, as a pet owner, might want to know about the fecal flotation tests performed by your veterinarian on your pet's stools: