|

Veterinary Information On Dog Whipworm (Trichuris vulpis).

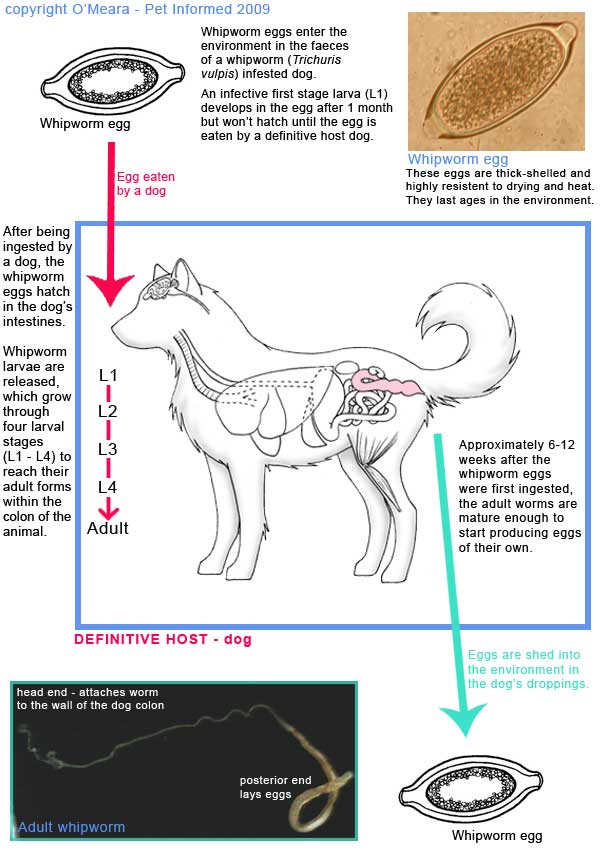

This dog whipworm page contains detailed, but simple-to-understand information on the canine whipworm parasite: Trichuris vulpis. The page contains photos of dog whipworms as well as a dog whipworm life cycle diagram for ease of understanding. Explanation of the dog whipworm life cycle is included, along with information on symptoms, diagnosis, treatment and prevention of whipworm in dog populations. Dog Whipworm - Contents: 1) What does dog whipworm look like? Contains photos of adult whipworms and whipworm eggs. 2) The dog whipworm life cycle diagram. 3) Symptoms of whipworm infestation in dogs. 4) How is canine whipworm infection diagnosed? Contains information on: fecal flotation of whipworm eggs; misdiagnosis of canine whipworm eggs (e.g. worm eggs that look similar to dog whipworm eggs) and how to interpret a positive result (i.e. what the significance of finding whipworm eggs on a fecal float is). 5) Treatment and prevention of whipworm infestations in definitive host dogs. 5a) All-wormer products that kill dog whipworms and how often to use them. 5b) Dealing with canine whipworm contaminated environments. 5c) Prevention of whipworms in large dog populations (e.g. boarding kennels, shelters, dog breeding facilities). 5d) Drug resistance - when the wormers are not removing the dog whipworms and treating the symptoms. 6) Can dog whipworms infest humans? This section includes info on human whipworm infestation with the non-canine species: Trichuris trichiura 1) What Does Dog Whipworm Look Like? It is very rare for pet owners to ever see dog whipworms. They are extremely small (a few centimeters at most), white worms

with incredibly thin bodies that are seldom ever noticed if they die and appear in the faeces of

their canine host. The only reason I managed to get pictures of the worms that appear

in the photos below was because I diagnosed whipworm eggs on a fecal float, wormed the affected

animal and then (oh yuck) sifted through the feces passed the next day until I found them. Even knowing in advance that the dead whipworms would be present within the feces did not make them easy to find. The things a vet will do to get you the photos!

Pseudo-Addison's (Pseudoaddison's) disease: Dogs with canine whipworm infestation can sometimes develop a condition called Pseudo-Addison's disease. The condition is so-named because animals affected with it will develop symptoms and blood-test results that closely mimic those of the endocrine disease: Addisons Disease (the medical term for Addison's Disease is hypoadrenocorticism). These animals will usually tend to show the above symptoms of colitis (with or without vomiting) and will often develop such severe dehydration and marked imbalances in their blood electrolytes - potassium and sodium (the potassium will be high and the sodium will be low) - that they will present to the vet clinic collapsed and in a severe state of shock (signs of shock include: low blood pressure, low oxygenation of the tissues, pale gums, cold extremities, low body temperature). Without urgent veterinary treatment, these animals may die from shock or from associated complications like heart arrhythmias (a critically low heart rate caused by high potassium levels), renal failure and sepsis. Author's note: Once the patient has been stabilized and is no longer in shock, a simple fecal float is often enough to diagnose the dog whipworm infestation (which is the 'preferred' diagnosis - whipworm disease is far easier to treat and cure than true Addison's Disease, which is often a costly, lifelong condition). 4) How is canine whipworm infection diagnosed?

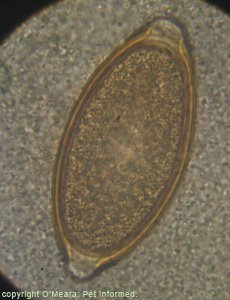

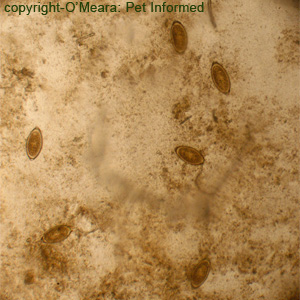

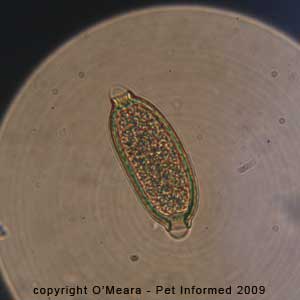

Dog whipworm infestation is generally diagnosed using a diagnostic test called fecal flotation. This is a test

that your veterinarian can often perform in-house (i.e. in the laboratory at the vet clinic)

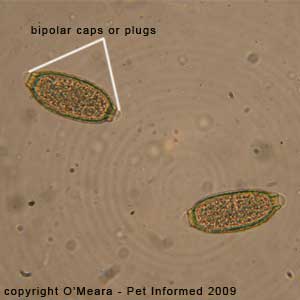

using a fresh sample of feces from your dog (or cat). Note: this author has not had any trouble finding dog whipworm eggs using simple sodium nitrate fecal flotation techniques (the image on the right shows some whipworm eggs that I found using sodium nitrate flotation medium), however, improved accuracy of detection would be expected using centrifugation and denser flotation solutions. Important author's note: Whipworm females do not produce and shed eggs constantly. They will often shed their eggs out into the environment intermittently. This means that a fecal float that is negative for dog whipworm eggs on one occasion may turn up a positive result on another occasion. A single fecal float that is negative for dog whipworm eggs should, thus, not be considered to 100% rule out the possibility of whipworms being present. Repeated fecal floats may be needed to say for sure whether or not a dog truly does or does not have dog whipworms. Important author's note: Animals with significant whipworm burdens can show symptoms of whipworm-related disease BEFORE eggs appear in the host's feces. Dog whipworms take 3 months to reach their adult, egg-producing stage in the canine intestinal tract. Thus, the worms have a window of 3 months in which to cause intestinal injury and symptoms of disease before any eggs appear, making diagnosis of early dog whipworm infestation potentially tricky. Worms whose eggs mimic those of dog whipworms: When diagnosing whipworm eggs on fecal flotation, it is important to remember that there are some other parasite eggs out there whose appearance strongly mimics those of Trichuris vulpis on a fecal float and whose disease significance is different to that of dog whipworm. For example, Capillaria eggs can occasionally be found in the faeces of dogs that are infested with Capillaria worms (see the Capillaria egg images below - these worm eggs look very similar to those of dog whipworm). Various Capillaria worm species inhabit a range of different sites within the animal body including: the respiratory tract, gut and bladder, where they generally produce little to no symptom of disease (they are generally considered to be minimally pathogenic to dogs). Note that certain species of Capillaria can cause severe disease signs in other non-canine hosts, including birds (e.g. gizzard Capillaria of birds) and rodents (e.g. liver worms of rats). As a side note, it should be mentioned that the name Capillaria is now defunct. The Genus Capillaria used to be a huge Genus made up of many individual types of worms. After much study, the worm species contained within the collective Genus name Capillaria have since been found to be different enough that they have been ascribed new and different Genus names including: Eucoleus, Pearsonema, Aonchotheca, Calodium (rat liver worm), Hepaticola and Thominx, which they are now officially known as. I will elect to use the term Capillaria to describe all these closely-related worms with the whipworm-like eggs, since this is the Genus name that is the more well-known in the literature. Just remember, however, that when I call a worm Capillaria, I am really referring to a worm species that is most likely to now be termed Eucoleus, Aonchotheca or Pearsonema or some other Genus name. Whipworm eggs and whipworm-like eggs can appear in the feces of dogs who eat the feces of other animals. Capillaria eggs may also appear (on a fecal float) in the feces of a dog that has been consuming the droppings of other, Capillaria-infested animals. For example, a dog who had eaten some Capillaria-infested bird droppings might have bird Capillaria eggs appearing in the fecal float. Capillaria eggs can travel through a dog's intestinal tract unchanged and appear in its faeces. These Capillaria eggs need to be differentiated from those of true dog whipworm. Similarly, true whipworm eggs may also appear in the feces of a dog that has been consuming the droppings of other, whipworm-infested animals (for example, a dog who had eaten some Trichuris ovis-infested sheep droppings might have sheep whipworm eggs appearing in its feces on fecal float). Species of whipworms (whose eggs look very similar to those of dog whipworm) do infest other types of animal hosts including: cattle (infected with Trichuris discolor), sheep (infected with Trichuris ovis), pigs (infected with Trichuris suis) and humans (infected with Trichuris trichiura). Dogs may ingest these 'other' kinds of whipworm eggs through the consumption of feces passed by infested host animals or humans. These 'other' whipworm eggs will travel through the dog's intestinal tract unchanged and appear in the dog's faeces. They will not tend to hatch out in the dog's gut and so do not pose a risk of infestation for the dog. As a final note, it should be remembered that dogs who consume the fresh, whipworm-egg-bearing feces of other dogs will show up positive for dog whipworm eggs on a fecal float. The dog whipworm eggs contained in the fresh droppings will travel through the consumer-dog's intestinal tract unchanged and appear in that dog's faeces. The reason those whipworm eggs do not hatch and infest the fecal-consuming animal, even though the consuming animal is the correct species for them, is because the freshly-passed whipworm eggs have not yet developed an infective L1 larva. Dog whipworm eggs need to sit in the environment for 1 month before becoming infective to a new canine host (by this stage, any fecal matter will have broken down).    Bird Capillaria egg pictures: This is a close-up microscope picture of a fecal float test performed on a Currawong bird with weight loss and diarrhea. Several Capillaria eggs are visible in these parasite pictures. The Capillaria eggs are the yellow-brown, oval-shaped (rugby-ball shaped) structures seen in the three images. They have thick walls and a pale cap-like structure on each pole ("bipolar blebs"). They look very similar in appearance to canine whipworm eggs (Trichuris). I personally think that the caps (blebs) of whipworm and Capillaria eggs look different. Confirming that eggs seen are dog whipworm eggs: If eggs found on a fecal flotation test are thought to be dog whipworm eggs, this can be confirmed by deworming the animal with an "All-wormer" tablet and looking for the adult whipworms in the feces (wear gloves if handling feces) over next 12-36 hours. Finding the characteristic "whip-like" worms is proof that the eggs seen were dog whipworm eggs and not Capillaria ova or eggs from a non-canine species of whipworm (i.e. eggs just passing through as a result of fecal consumption by the dog). The significance of a 'positive' fecal float: If dog whipworm eggs are found on a fecal float, this does not automatically mean that they are responsible for causing a dog's clinical signs, even if those clinical signs do seem to 'fit' with a diagnosis of canine whipworm infestation (e.g. diarrhea, fresh, red blood in the stools). Whipworms in low numbers often cause no clinical symptoms in dogs and eggs can often be found co-incidentally on a fecal float test in these animals. A dog with inflammatory bowel disease (an immune-mediated bowel allergy disorder, which can be characterized by colitis and diarrhea signs) who happens to have a small burden of whipworms may be mistakenly diagnosed as a 'whipworm case' on a fecal float when the true problem is an allergic bowel disorder (IBD). A good way to determine the disease significance of any whipworm burden present is to deworm the dog (with an "All-wormer" product) and see what happens. If symptoms attributed to the parasite's presence (e.g. diarrhea, colitis-signs) resolve after worming, this is often a pretty good clue that the parasites probably played a role in causing the disease symptoms seen in the patient. Dog whipworms can also be found by colonoscopy: Sometimes whipworm eggs are not found on routine fecal flotation testing and the vet does not diagnose the canine whipworm infestation. Should the vet end up performing a colonoscopy on the canine patient, the worms will often be clearly visible hanging from the walls of the large intestinal tract (the worms are easily spotted on colonoscopy). A colonoscopy is a procedure whereby the veterinarian anesthetises the animal and inserts a tiny video-camera (called an endoscope or colonoscope) up the animal's anus and into the large intestinal tract. This allows the veterinarian to visually examine the lining of the animal's rectum and colon (large intestine) for signs of disease. 5) Treatment and prevention of canine whipworm infestations in definitive host dogs. 5a) Killing whipworms with antihelmintic medications or "All-wormers" All-wormer products that kill dog whipworms and how often to use them. Adult dog whipworms can be eliminated from the host canine's intestines using a range of anti-nematodal medications including: febantel, milbemycin oxime, pyrantel, ivermectin, oxantel and fenbendazole among others. These drugs are usually contained alone or in combination in deworming tablets called "All-wormers", many of which can be purchased from your vet or even from the local supermarket.  IMPORTANT author's note: Be careful in your interpretation of the term "All-wormer." You'd think from this term that the product bearing the label kills ALL WORMS. It doesn't. "All-wormers" generally only kill all parasitic worms that invade the intestinal tract of the intended host animal. Worms that invade other regions of the body (e.g. the heart in the case of heart worm and the lung in the case of lungworm) often are not killed by routine "All-Wormer" tablets.

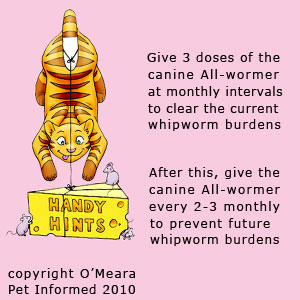

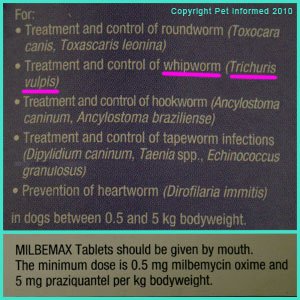

IMPORTANT author's note: Be careful in your interpretation of the term "All-wormer." You'd think from this term that the product bearing the label kills ALL WORMS. It doesn't. "All-wormers" generally only kill all parasitic worms that invade the intestinal tract of the intended host animal. Worms that invade other regions of the body (e.g. the heart in the case of heart worm and the lung in the case of lungworm) often are not killed by routine "All-Wormer" tablets. Author's Tip: It is easy to tell if a worming tablet kills whipworms. Just look on the back of the pack! The names of the worms killed by the tablet are usually listed. Just look for the common name: "whipworm" or the scientific name: "Trichuris vulpis" to see if the wormer you've chosen will be appropriate. Most drugs used to kill whipworms in the canine gut are pretty safe for your dog, even if given at doses above the recommended rate. When an adequate dose of anti-nematodal drug is administered to the definitive host animal, the whipworms usually die and are voided in the host animal's feces (as mentioned previously, it is rare for pet owners to actually spot these tiny worms in their animal's feces). This single treatment can often be curative, however, several doses may be needed to completely rid an animal of a large whipworm burden, particularly if a range of whipworm age groups (ranging from L2 to adult stage) is present. Some texts suggest that younger worms may not be as susceptible to antihelmintic drugs as adult worms and that these worms may need to grow to their mature adult stage before the wormers will clear them. It is therefore recommended that appropriate doses of an appropriate all-wormer drug be given at monthly intervals over three months to clear all whipworms present (this is because young worms take about 3 months to reach adulthood).  Most deworming medications do not generally last very long in a treated-animal's system. When an all-wormer medicine is given to a pet, the drugs generally work rapidly, killing off the adult worm parasites in one hit, before quickly disappearing from the animal's system. The implication of this is that the de-worming drugs do not hang around to protect the pet against subsequent worm infestations. Should that pet continue to consume dog whipworm eggs from contaminated grass and soil in the days following

a deworming treatment, it will most likely become rapidly re-infested with adult whipworms, starting the

problems and the symptoms of whipworm disease all over again. It is thus important to reduce a pet's exposure to

whipworm infested environments (see next section 5b) to help prevent future dog whipworm burdens from forming.

Most deworming medications do not generally last very long in a treated-animal's system. When an all-wormer medicine is given to a pet, the drugs generally work rapidly, killing off the adult worm parasites in one hit, before quickly disappearing from the animal's system. The implication of this is that the de-worming drugs do not hang around to protect the pet against subsequent worm infestations. Should that pet continue to consume dog whipworm eggs from contaminated grass and soil in the days following

a deworming treatment, it will most likely become rapidly re-infested with adult whipworms, starting the

problems and the symptoms of whipworm disease all over again. It is thus important to reduce a pet's exposure to

whipworm infested environments (see next section 5b) to help prevent future dog whipworm burdens from forming. Following the ingestion of a mature, infective, L1-larvae-bearing whipworm egg (i.e. an egg that has been sitting in the pet's environment for at least 1 month), a definitive host dog (or cat) can have a reproductively-mature, egg-shedding adult whipworm inside of its large intestinal tract within 3 months. In situations where loads of long-lasting whipworm eggs have contaminated the pet's environment, a pet owner will need to repeat worm his dog (or cat) every 2-3 months to keep the adult whipworm numbers under control!  Dog whipworm treatment: This is a photo of the back of the box of an All-Wormer product called Milbemax. The box states that it kills whipworms and has both the common name (whipworm) and the scientific name (Trichuris vulpis) listed. I have underlined these in pink. 5b) Dealing with canine whipworm contaminated environments. Most deworming medications do not generally last very long in a treated-animal's system. When an all-wormer medicine is given to a pet, the drugs generally work rapidly, killing off the adult worm parasites in one hit, before quickly disappearing from the animal's system. The implication of this is that the de-worming drugs do not hang around to protect the pet against subsequent worm infestations. Should that pet continue to consume dog whipworm eggs from contaminated grass and soil in the days following a deworming treatment, it will most likely become rapidly re-infested with adult whipworms, starting the problems and the symptoms of canine whipworm disease all over again. Following the ingestion of a mature, infective, L1-larvae-bearing whipworm egg (i.e. an egg that has been sitting in the pet's environment for at least 1 month), a definitive host dog (or cat) can have a reproductively-mature, egg-shedding adult whipworm inside of its large intestinal tract within 3 months. In situations where loads of long-lasting dog whipworm eggs have contaminated the pet's environment, a pet owner will need to repeat worm his dog (or cat) every 2-3 months to keep the adult whipworm numbers under control! Because dog whipworm eggs can last so long in a pet's environment (eggs have been known to last up to 7 years in a contaminated environment), it follows that, so long as an animal remains situated in an environment where lots of whipworm eggs can be found, that animal WILL very likely become reinfected with whipworms the second that medicated worm prevention (worming) is allowed to lapse (i.e. if the owner forgets to give the de-worming tablets for a couple of months, the animal will surely become reinfested again). It is therefore helpful if a pet can be removed from a whipworm-infested site. A pet housed in an area that has not had whipworm contamination before is unlikely to get the parasite. What is a whipworm infested site? A whipworm infested site is any site that has been exposed to dog feces bearing dog whipworm eggs (i.e. a site that a whipworm-infested dog has had access to) AND which has not been adequately cleaned enough to remove them (i.e. letting them remain in the environment). The second part is important. A dog with whipworms can defecate in a steel vet clinic cage, exposing that cage to whipworm, but the site is unlikely to become 'whipworm infested' nor pose a risk to future dogs entering the cage because vet clinic cages are extremely easy to clean. An attendant can clean the steel cage well, removing it of the whipworm eggs quite easily. This is one reason (ease of cleaning and disease control) that vet clinics keep animals in smooth steel housing. In contrast, it is difficult to clear whipworm eggs out of moist soil, sand, lawn and vegetation. Once the feces carrying the dog whipworm eggs break apart, the eggs trickle deeply into the soil and lawn bed where they can not be removed (not without digging up the lawn or the soil anyway). Those eggs then sit in these sites for a month and become L1-bearing and hence infective. The eggs can then persist for years in this infective state. Author's note: It is very important for attendants to pick up and dispose of all dog feces the moment the dog passes them. If feces are not given the chance to break down on lawns or soil, they will release fewer eggs into the environment. What if you can not remove the animal from a whipworm-contaminated site? It is all very well to say "move the dog away from the site containing the whipworm eggs", but some of us can't do that. We have one yard or one breeding or boarding kennel facility and that is all we have to work with, even if it becomes infested with dog whipworm eggs. If this is the case, you have several solutions: 1) De-worm regularly - every animal on the premises should be wormed with an appropriate dose of an all-wormer drug every 2-3 months (you can even do it monthly if you like). 2) Same-day worming - every animal on the premises should be wormed on the same day. 3) Weigh before worming - every animal to be wormed must be weighed so that the correct dose of wormer is given. 4) Rotate all-wormers - see section 5d on prevention of whipworm drug resistance. 5) Change wormers if the one you are using does not seem to be working - 5d. 6) Pick up and remove all feces from the yard the second the dog passes them - if the feces are passed onto lawn or soil, some people will use a shovel and remove the section of dirt or lawn that the feces made contact with (just to be extra sure of removing all of the fecal matter). 7) House animals on sand, concrete or gravel - These surfaces, particularly concrete, are easier to disinfect than soil or lawn and they tend to become very hot if exposed to direct sunlight (direct sun and intense heat may kill whipworm eggs, rendering them non-infective to pets). 8) Bleaching and steam-cleaning - Surfaces like gravel and concrete can be regularly bleached and steam-cleaned. Steam-cleaning in particular is non-harmful to staff and animals and can be quite beneficial in killing environmentally resilient eggs and oocysts like those of dog whipworms, roundworms and coccidia. 9) If soil or lawn is the chosen surface for housing dogs, regularly replacing the soil or lawn every 3-6 months should reduce whipworm egg burdens. If you replace the soil or lawn with non-contaminated soil or lawn and then thoroughly deworm all the dogs (three doses each given 1 month apart) before re-introducing them to the clean surfaces, you should not need to replace the soil and lawn anywhere near as often (particularly if you remain vigilant about not letting untreated dogs access the sites and if you maintain strict monthly worming protocols with the dogs already there). 10) Remember that moist, cool, shaded soils, mud and lawns are the worst for harbouring viable whipworm eggs - you might want to consider housing pets on concrete or gravel if you come from a site with cool to warm climate, dense shade and high humidity and rainfall. 5c) Prevention of whipworms in large dog populations (e.g. boarding kennels, dog breeding facilities). Dog whipworm burdens tend to become most problematic in environments where many dogs are housed close together, sharing some communal areas (e.g. walking areas, exercise yards, training yards) and alternating through other areas (e.g. kennels and housing yards). Facilities such as: boarding kennels, breeding facilities, animal shelters (particularly those with "long-stay" policies), pounds and places that keep large numbers of working dogs (e.g. farms, police dog units, army dogs units, rescue dog units) are particularly at risk. Over time, resistant eggs build up in the environment, posing a risk of infestation to the dog populations that actually dwell there and to those dogs that just pass through. There are many ways to help reduce whipworm build-up and spread in these multi-dog facilities. Many of these have been touched on in the above section (2b), but I have also listed some additional tips and hints to help keep dog whipworms under control. De-worming of current animal populations: Every animal on the premises should be wormed with an appropriate dose of all-wormer drug every 2-3 months. If dog whipworm is a particular problem, monthly de-worming can be scheduled as part of the kennel worming protocol. Every animal on the premises should be wormed on the same day. Every animal on the premises should be weighed before worming. This is to ensure that the correct dose of wormer is given. This is particularly important in puppies whose weight can change radically from month to month. IMPORTANT - All-wormers should be 'rotated' to help prevent the onset of whipworm drug resistance in a facility (see section 5d). Basically, all this means is that, every time the animals in the kennel facility are de-wormed, an all-wormer product with a different active ingredient is selected (this changing of drugs should kill off any 'resistant' worms that might have survived the previous all-wormer drug given). Quarantine and de-worming of incoming animal populations: Kennel facilities accepting new dogs should ideally have a set of easy-to-disinfect and steam (concrete, steel or gravel flooring) dog runs located well away from the main dog population (this is called a quarantine zone). New dogs entering the premises should be placed in these quarantine runs for around 6-8 weeks or more and repeatedly de-wormed with all-wormer. Ideally it is recommended that 3 doses of all-wormer be given at monthly intervals, necessitating a 12 week stay in quarantine. Certainly, if dog whipworm is a major issue in your region, this is advisable. 12 weeks may, however, be overkill and giving at least 2 doses, a month apart, before letting the animal into the general population may be sufficient (the animal will still receive the third dose a month later). How long an animal stays in quarantine really depends on all of the diseases and parasites likely to be found in the particular population and on the animal intake rate and space availability and funds of the premises (for example, high-intake shelters may not have the luxury of long-term quarantining of animals). The general rule, however, is that the longer an introduced animal stays in quarantine the better for the premises as a whole. Animals can be screened for dog whipworm eggs using fecal flotation tests prior to introducing them to the general population. This screening can be a useful way of detecting active whipworm shedders prior to their entry into the main populace. If eggs are found, the animal should stay in quarantine for further de-worming until eggs are no longer being discovered. Note that incoming animals can be fully wormed (12 weeks worth) prior to their arrival on your site. Not having to keep animals in quarantine purely for the purposes of complete worming could well help to reduce the length of time the incoming animals remain in the quarantine runs. Strict removal of all dog faeces: All feces that a dog passes should be cleaned up from exercise yards and kennels the second they are noticed. This will prevent dog whipworm eggs from entering the environment, giving them no chance to develop larvae (L1s) and become infective. If feces are passed onto soil or grass, it is a good idea to use a shovel and remove the section of dirt or lawn that the feces made contact with (just to be extra sure of removing all of the fecal matter). Choose flooring that will not hold and harbour whipworm eggs and which is easy to disinfect and steam-clean: Keeping dogs in kennels with smooth, hard, easily-bleached, easily-steamed flooring (e.g. tiles, lino, concrete, gravel, stone) is a great way of keeping all manner of disease nasties under control in big animal populations, not just canine whipworms (e.g. parvo, coccidia, hookworms). Such surfaces, particularly concrete, are easier to disinfect than soil or lawn and tend to become quite hot if exposed to direct sunlight (direct sun and intense heat may kill whipworm eggs, rendering them non-infective to pets). Note that such surfaces should be shaded to prevent foot-burns in animals. Surfaces like gravel and concrete should be regularly bleached and steam-cleaned. Steam-cleaning in particular is non-harmful to staff and animals and can be quite beneficial in killing environmentally resilient eggs and oocysts like those of dog whipworms, roundworms and coccidia. If soil or lawn is the chosen surface for housing dogs (and, let's face it, it looks and feels better), regularly replacing the soil or lawn every 3-6 months should reduce whipworm egg burdens significantly (albeit at significant cost). If you replace the soil or lawn with non-contaminated soil or lawn and then thoroughly deworm all the dogs (three doses 1 month apart) before re-introducing them to the clean surfaces, you should not need to replace the soil and lawn anywhere near as often (particularly if you remain vigilant about not letting untreated dogs access the sites and if you maintain strict monthly worming protocols with the dogs already there). Remember that moist, cool soils, mud and lawns are the worst for harbouring viable whipworm eggs, parvovirus and hookworms. You should consider housing pets on concrete or gravel if you come from a site with cool to warm climate and high humidity and rainfall. If you do this, however, do make sure that the flooring is well-drained and not prone to forming puddles. Animals that are forced to stand around on hard, abrasive surfaces in wet conditions will often get sores and nasty infections on their feet similar to those moisture-associated bacterial and fungal conditions seen in poultry and livestock (e.g. bumblefoot, greasy heel, thrush). Rotate wormers and periodically 'rest' dog pens: As mentioned above, all-wormers should be 'rotated' to help prevent the onset of dog whipworm drug resistance in a facility (see section 5d). Basically, all this means is that, every time the animals in the kennel facility are de-wormed, an all-wormer product with a different active ingredient is selected (this changing of drugs should kill off any 'resistant' worms that might have survived the previous all-wormer drug given). Similarly, it can also be helpful to periodically 'rest' each block of dog kennels or cages, leaving them free of dogs for a couple of months at a time. Resting blocks of kennels for a good few months, the moment a block is free of dogs (e.g. after all the animals in the block have been sold or weaned or moved to other kennel locations) allows that block to be fully cleaned out, scrubbed, bleached, steamed and opened up to the sun for a couple of months, thereby rendering the region clear of infective organisms and parasites (i.e. nice and ready for the next intake of dogs). Runs with soil or grass can be resurfaced with new soil or lawn in that time. Note that rotating and resting dog kennels, pens or runs does require that a premises (e.g. shelter, boarding facility, breeding kennels) be only kept at about 80% of its full carrying capacity. This may not be financially feasible for some premises. Periodically screen dog feces samples for worms: In order to tell how effective your worm control protocols are being, you can periodically collect and screen dog feces for evidence of worms. Performing fecal flotation tests on fecal samples from across the dog population will not only tell you if your overall worming protocol is effective, it will help you to trouble-shoot problem areas (maybe worms are turning up in only one block of cages, telling you that there is an issue with cage-cleaning going on there or a staff-member who is not giving the de-worming medications). 5d) Drug resistance - when the wormers are not removing the dog whipworms and treating the symptoms. Sometimes owners of domestic pets and managers of large multi-dog kennel facilities appear to do all the right things and worm all of their animals regularly only to find that symptoms of dog whipworm disease continue to persist in their population. They start to ponder if they have a 'drug resistant' dog whipworm population and wonder what they can do about it. There are two aspects that should be considered when looking at the issue of de-worming failure: 1) Is the problem at hand truly drug resistance (as in: the worms are actually immune to the antihelmintic drugs being given) or is there some other simple failure of worm control going on? 2) Are the symptoms of disease being seen actually the result of dog whipworm infestation? 1) Is the problem at hand truly drug resistance (as in - the worms are truly immune to the antihelmintic drugs being given) or is there some other simple failure of worm control going on? Drug resistance in whipworm populations:

http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/trichuriasis.pdf Your dog whipworm links: Please note: the scientific tapeworm names mentioned in this dog whipworm life cycle article are only current as

of the date of this dog whipworm web-page's copyright date and the dates of my references. Parasite scientific names are constantly being reviewed and changed as new scientific information becomes available and names that are current now may alter in the future. |