Veterinary Advice Online - The Lice Life Cycle.

Lice infestation is one of the great banes in life for many pet, poultry and livestock owners.

Lice infestation is one of the great banes in life for many pet, poultry and livestock owners.

These rather-common insect parasites pose a variety of problems for pets, production animals (e.g. livestock, poultry) and their owners including:

- lice bites - nymph and adult lice bite or pierce the skin of the host animal/s, causing pain, redness and itching of the bite site.

- coat and feather damage - pets (e.g. birds, poultry, cats, dogs)

and livestock (e.g. cattle, sheep and horses) that are used for breeding and showing purposes

can be penalised in the show ring if their fur (or plumage) is damaged by scratching and over-grooming activities or if it bears the evidence (lice, nits) of lice parasite infestation.

- fleece or wool damage (goats, sheep) - goats and sheep infested with biting or sucking lice species

spend a good deal of their time scratching and biting and rubbing (against trees and fences) at the insects in the coat, which results in damage to the hair coat and skin. This can result in significant wool damage to wool-producing sheep and goats (e.g. Merinos, Angoras), which can result in the farmer being penalised at the market (ruined wool does not sell for a good price).

- ill-thrift and meat or milk production losses (livestock, pigs, poultry) - livestock

and poultry infested with lice spend a good deal of their time scratching and biting at the insects in the coat (plumage). The intense itchiness can result in reduced time spent grazing or feeding, which can result in the animal becoming thin (ill-thrift) and not growing well. This ill-thrift can have a negative impact on the profits of farmers who are trying to grow livestock and poultry animals for their meat. Likewise, the stress of

severe lice infestation can also have a negative impact on milk production in animals that are

farmed for their milk (e.g. cows, goats and sheep).

- financial cost of lice treatments - in order to control lice infestations

in animals, pet and livestock owners need to spend money on insecticide treatments. These treatments

can be expensive, particularly if large numbers of animals need to be treated (e.g. a herd of cattle or pigs).

- lice insecticide contamination of meat, milk, hides and wool - it

is possible for some of the chemicals used in the control of lice infestation to contaminate the

meat, milk, hides and wool of the treated animal/s. These often-toxic residues may subsequently contaminate and accumulate within the bodies of humans who handle or consume these animal products, resulting in future health problems. High insecticide

residues in animal products can potentially ruin a farm's trading and export opportunities.

- lice insecticide contamination of the environment - it

is possible for some of the chemicals used in the control of lice infestation to contaminate the

environment (e.g. waterways, yards, soil) of the treated animal/s. These toxin residues may subsequently contaminate and accumulate within the local waterways and environment (air, soil, vegetation etc.)

resulting in health problems (e.g. cancers and birth defects in people drinking the contaminated water), animal deaths (e.g. fish and marine animal deaths) and altered ecosystems (e.g. massive fish kills leading to unnaturally large increases in insect numbers and so on). High environmental insecticide residues can potentially ruin a farm's ability to achieve organic status.

- skin disease - louse infested skin that is traumatized by lice bites and by animal scratching and biting activities can become secondarily infected with nasty, itchy, skin bacteria.

- anemia - heavy sucking lice infestations can draw so much blood from their animal host that the host can weaken and even die from severe blood loss (anaemia).

- infectious disease transmission - some infectious diseases including: flea tapeworms (Dipylidium caninum) and human typhus (Rickettsia prowazekii)

can be transmitted from animal to animal or human to human by lice parasites.

- annoyance - most owners don't like to see or hear their pets scratching, particularly at night when the repetitive 'chink, chink, chink' of a collar or chain keeps them awake.

- gross-out factor - the sight of insects crawling through a pet's fur is revolting and off-putting to many people who see such infestations as a sign of 'dirtiness' (even though perfectly clean pets and humans can and do get lice of course).

Because of the many problems posed by lice (above), there is, naturally, a lot of vested interest in the control and prevention of louse parasites, both in the home and commercially.

Many millions of dollars are spent each year in the manufacture and production of newer, safer, better lice control and louse killing products and, in their turn, pet owners and commercial producers

of animals (animal breeders, animal showers, poultry farmers, livestock meat producers, livestock wool producers and so on) spend even more millions buying these newer, better, safer lice prevention products in the hope of preventing and/or eradicating their louse infestation problems.

In order for pet owners and commercial animal producers to understand how lice are transmitted and

to appreciate how and why lice infestations become so large and so persistent, it is important for them to examine the lice life cycle (see section 1). The lice life cycle is the complete cycle of a louse's existence: from egg to nymph stage (three nymph stages) to adult stage, to egg stage again with the next generation. The lice lifecycle tells us: how and where the lice parasite reproduces;

where the juvenile forms (egg, nymph) of the lice life cycle exist; how long each of the life cycle

stages last; whether we should look for any off-host sites of re-infestation and what forms

of treatment and retreatment are likely to be effective. The lice life cycle is very important to know if a lice infestation

is to be controlled adequately and permanently. The life cycle of lice can provide important clues as to why a particular louse control regime is not working and an explanation as to why the parasites keep on coming back.

Stopping an infestation of lice from persisting involves breaking the lice life cycle at any point

in the lice life cycle chain: from egg to nymph stage to adult stage

(see lice life cycle diagram in section 1). The more points that can be broken (via treatment) in that chain or lifecycle, the faster lice control will be achieved and the more permanent the results will be.

This webpage contains a detailed, but simple-to-understand explanation of the

complete lice life cycle. It comes complete with a full lice life cycle diagram for ease of understanding. As an added bonus, the significance of each stage of the lice life cycle and how it can be interpreted, managed and manipulated in order to achieve better lice control and lice prevention results is also discussed in full. All louse control in pets revolves around an understanding of the life cycle of lice. Enjoy.

The Lice Life Cycle and How It Guides Effective Louse Control and Prevention - Contents:

1) The lice life cycle diagram - a complete step-by-step diagram of animal host lice infestation and

lice reproduction.

2) How the lice life cycle is used to guide effective lice prevention and lice control.

The Lice Life Cycle and How It Guides Effective Louse Control and Prevention - Contents:

1) The lice life cycle diagram - a complete step-by-step diagram of animal host lice infestation and

lice reproduction.

2) How the lice life cycle is used to guide effective lice prevention and lice control.

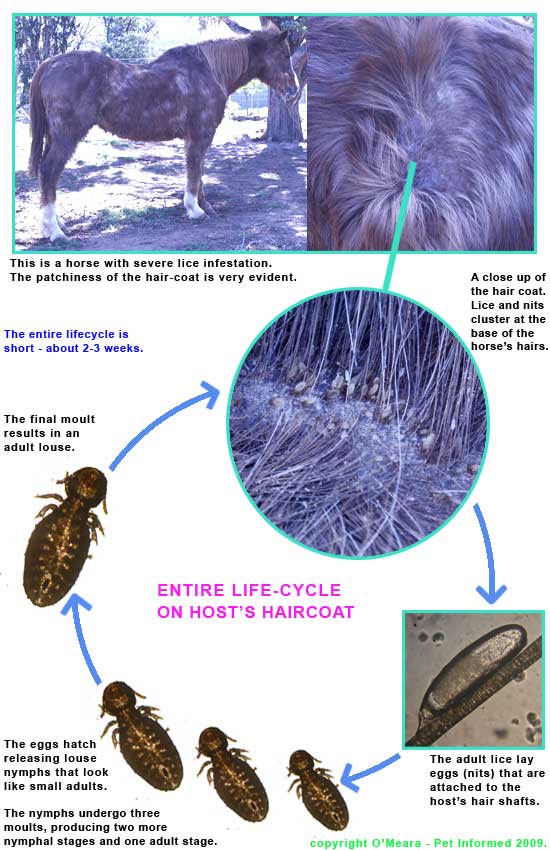

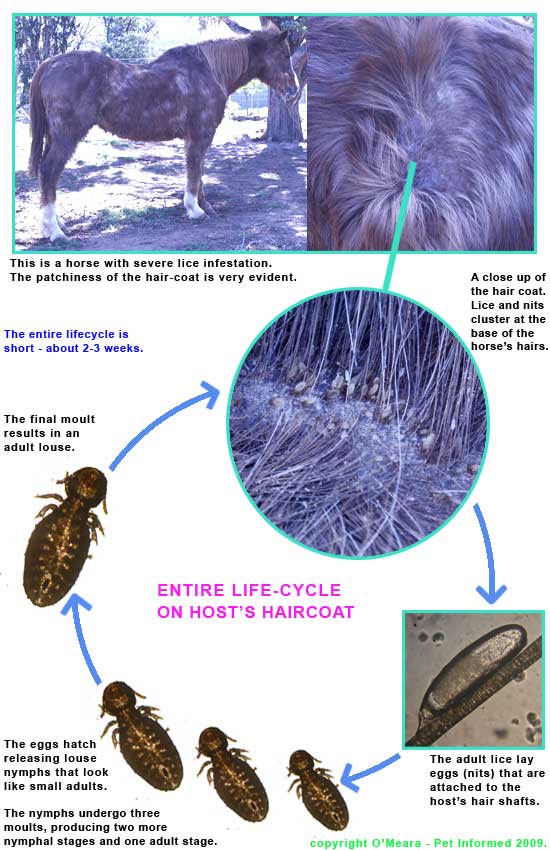

1) The Lice life Cycle Diagram:

Lice life cycle diagram:

This is a flow diagram of the lice lifecycle as it applies to the vast majority of lice species. The most important thing to understand from this lice life cycle diagram is that the entire life cycle of lice occurs on the coat or plumage of the host animal (in this case: the horse's fur).

There is no stage of the lice lifecycle that occurs "off-host" in the host animal's environment.

The timing of the various stages:

- Egg - The lice egg (lice nit) stage of the lice life cycle hatches in 7-14 days, depending on the species of lice and on environmental conditions.

- Three nymph stages - The three nymph stages of the lice life cycle grow and undergo their molts over about 9-22 days, depending on the lice species in question.

- The adult louse - Adult lice usually live for 2-3 weeks on the fur of the host animal. They will lay eggs during this period. Thus the lice life cycle continues ...

This particular diagram illustrates the life cycle of the horse lice species:

Damalinia equi (the horse

biting louse), however, the diagram shown would also be appropriate to a vast range of other lice types, including:

Trichodectes canis (the dog lice or canine lice);

the cat louse (

Felicola subrostratus);

the horse sucking louse (

Haematopinus asini);

the various sucking lice species infesting livestock (

Linognathus and

Haematopinus species);

the various biting lice species infesting livestock (various

Damalinia or

Bovicola species);

the rat sucking louse (

Polyplax spinulosa);

the mouse sucking louse (

Polyplax serrata - images

below);

the various guinea pig lice species and

the various human lice species.

The main differences between these other lice life cycle situations and that of

Damalinia equi (pictured) would be the host animal species infested by the lice (e.g. the dog host instead of the horse host for

Trichodectes canis) and the unique opportunities for host-to-host transmission

of lice that might crop up, depending on the unique lifestyle of the host species in question (e.g. lice spread from horse to horse via horse brushes, tack-sharing and the sharing of lice or nit infected rugs in the case of

Damalinia equi versus lice spread from sheep to sheep

through close body contact in a flock situation or through the sharing of lice or nit infested shearing equipment

in the case of

Linognathus ovillus).

Lice life cycle picture 1

Lice life cycle picture 1 - This is the lice egg (nit) of the mouse louse

Polyplax serrata.

Lice life cycle picture 2 - This is the nymph stage of the mouse louse

Polyplax serrata.

Lice life cycle picture 3 - This is the adult stage of the mouse louse

Polyplax serrata. The body of the adult louse is longer and more highly-developed than that of the immature

nymph stage of the lice life cycle.

2) How the lice life cycle is used to guide effective lice prevention and lice control:

2) How the lice life cycle is used to guide effective lice prevention and lice control:

Looking at the lice life cycle diagram above, the most important concept to understand is

that the entire life cycle of the louse (from egg to adult back to egg again) takes place

on the fur or plumage of the host animal. The adult lice and their newly hatched nymphs need to remain on the host animal's body to feed and survive (they will not survive long off a host animal's skin - hours to days only).

If a louse egg falls off a host and into the environment, unless there is a massive density of potential hosts

milling around, there is very little chance that the nymph which hatches out of it will encounter a host animal's coat prior to succumbing to the elements (lice nymphs are tiny, slow moving insects

with no ability to jump and no wings - they can not simply spring aboard a new host like jumping fleas and flying insect parasites can). For this reason, lice have taken the precaution of literally gluing their eggs to the host animal's pelt

so that there is maximum chance of nymphs hatching out in the presence of the target host's coat.

For this reason (that the lice life cycle takes place pretty much entirely on the host animal's coat),

lice are generally transmitted from host to host through

direct host animal contact (i.e. animals brushing up against

each other, animals running together in a flock, animals fighting, animals mating, animals sleeping in common nesting sites

and so on). Lice can not afford to accidentally fall into the environment (they will usually die if they enter the environment)

so they usually wait for host animals to be touching before making the move onto a new host animal. Consequently, the biggest risk to a non-lice-infected host animal of catching lice is not the

environment it lives in, but the presence of and contact with other lice-infested host animals

of the same species (lice are host specific and will only pass between hosts of the same animal species).

Lice eggs and live forms (nymphs, adults) will only enter the off-host environment if they are attached to hairs or feather shafts that are suddenly shed or otherwise lost

from the host (e.g. infested wool fibers sheared off with the fleece during shearing time; lice-infested hairs scraped off onto fences or trees through the scratching activities of lousy livestock; nit-infested hairs brushed out with combs or brushes and infested hairs rubbed from the coat by the abrasive motions of rugs and blankets). These

lost lice eggs will hatch out (within 2 weeks) in the open environment where the hair has fallen (paddocks, yards, floats, transport trucks, fence posts, trees, stalls, aviaries, runs, kennels and so on) and/or in the items that the nit-infested hairs have become entrapped in (e.g. blankets, rugs, bedding, brushes, combs, shearing equipment, pet carriers and so on) and, while the eggs remain viable and the newly-hatched nymphs remain alive, these items or areas should be considered

infectious to other host animals. Placing a "clean" (not-infested) animal into a small yard, stall, run or cage where lice infested animals have recently been housed (especially if it was within the last 3 weeks) poses some likelihood of that clean animal catching lice from the environment because freshly hatched nymphs may still be alive. Likewise, using a nit-or-lice-contaminated blanket, bed, brush or comb on a "clean" animal (especially if the louse-infested animal was exposed to the item within the last 3 weeks) also poses a high risk of lice transmission.

A) Lice Prevention:

From the lice life cycle and lice transmission information presented above, it should be self-evident

that there are two main ways of preventing lice infestation from occurring in "clean" lice-free animals:

1) preventing "clean" animals from accessing and contacting lice infected hosts and

2) preventing "clean" animals from coming into direct contact with lice-infested environments and fomites (e.g. lice-bearing yards, aviaries, stalls, floats, beds, brushes, shearing gear, tack, blankets and so on).

1) Preventing host-to-host lice transmission:

- Check the fur or feathers of new animals thoroughly for lice before introducing them to "clean" herds or flocks;

- Routinely treat all new animals with lice medications before introducing them to "clean" herds or flocks (even if they do not seem infested);

- Do not overcrowd animals (animals with no space, pushed closely together will pass on lice more easily);

- Animals should not be overcrowded, malnourished, bullied, wormy, too cold/hot, ill or kept in otherwise unhygienic or neglected states that could cause excessive stress. Lice burdens tend to be larger in over-stressed animals, promoting the increased passage of lice from animal to animal.

- Do not let "clean" animals come into contact with animals of unknown lice or lice-treatment status (e.g. at shows, in breeding pavilions and so on);

- If such contact between hosts of unknown lice-infestation status is needed (e.g. during stud services), both hosts can be treated with a lice insecticide after contact to prevent lice populations from breeding and establishing (be sure the treatment is safe for pregnancy if mating was the reason for contact);

- Keep fences and runs intact and well-maintained so that "clean" animals can not escape and access lice-infected animals;

- Keep fences and runs intact and well-maintained so that wild or stray or feral animals can not access lice-free animals;

2) Preventing fomite-to-host lice transmission:

- Don't share brushes and combs between animals (especially if the animals' background and louse status is unknown);

- Clean brushes and combs thoroughly before using them on a new animal (no shed hairs should be visible in the teeth/bristles of the brushes and combs);

- Brushes and combs used on louse infested animals should be treated with an effective insecticide louse killer and thoroughly rinsed and cleaned of all hairs before being used on any other animals. Resting the items for 3-4 weeks

before reuse (or resting them for 2 weeks and retreating them with insecticide, where practical and safe) is also advised.

- Don't share bedding, blankets or rugs between animals (especially if the animals' background and louse status is unknown);

- Clean bedding, blankets or rugs thoroughly before using them on a new animal (no shed hairs should be visible). Hot machine washing and steam cleaning can be useful here to ensure cleanliness (ideally bedding and the like should never be shared between different animals);

- Bedding, blankets or rugs used on louse infested animals should be treated with an effective insecticide louse killer and thoroughly rinsed and cleaned of all hairs before being used on any other animals. Disposable lice-affected bedding (e.g. old towels) should be thrown away after use. Resting the items for 3-4 weeks

before reuse (or resting them for 2 weeks and retreating them with insecticide, where practical and safe) is also advised.

- Clean shearing equipment thoroughly between animals in a flock (no shed hairs should be visible);

- Avoid shearing lice infected animals, particularly if there is a chance of non-infected animals being exposed to the same equipment (note that shearing of lice infested animals may be needed before certain

lice treatments can be applied);

- Do not let "clean" animals come into contact with environments (e.g. floats, stalls, trucks, yards, coops, aviaries) of unknown lice or lice-treatment status (e.g. at shows, in breeding pavilions and so on);

- If such contact with environments of unknown lice-infestation status is required, exposed animals

can be treated with a lice insecticide after contact to prevent lice populations from breeding and establishing in the coat;

- If possible, depopulate (remove all hosts from) yards, aviaries, chicken-coops, stalls, runs, cages, kennels and paddocks that have had lice-infected animals in them for at least 1 month (2 months to be safe). This host-free timespan will allow live lice to die and any eggs to hatch out and die, such that the site is no longer lice-infected. Widespread disinfecting with insecticide chemicals is possible for some kinds

of infected enclosures (e.g. aviaries, cages, runs, kennels), but it is not very safe for animals and personnel.

Widespread insecticide use should be avoided on large paddocks or yards due to the environmental impacts.

B) Lice Treatment:

From the lice life cycle information presented above, it should be self-evident that there are several important aspects to treating lice infestation in animals:

1) treat the infected host animals with an insecticide product to kill off the adult and nymph lice;

2) retreat all of the treated animals again in 14 days to kill off the nymph lice stages that have freshly emerged from any eggs that were present;

3) consider whether the environment or any infected fomites (lice-bearing yards, aviaries, beds, brushes, blankets and so on) need treating.

1) Tips and Hints on treating the infected host animals with insecticide:

- Treat ALL animals in the herd or group at the same time (untreated animals are a reservoir of lice re-infestation);

- Dose to appropriate weights (do not under dose or overdose);

- If using a rinse, shampoo, powder, spray, dip or wash, make sure that the entire coat or plumage is exposed to the insecticide so that no havens of live lice remain;

- Check the host's coat or plumage a day or so after treatment (wear gloves) to ensure that the treatment was effective;

- Make sure to make up the insecticide correctly (correct dilutions, correct storage, correct route of administration and so on);

- Make sure to store and use insecticide correctly (correct storage, nothing out of date, nothing stored in heat or open-sunlight and so on);

- Use according to label instructions - e.g. some sheep and goat lice treatments need to be applied within a certain time of shearing;

- ONLY use lice treatments on the animals they are intended for (i.e. do not treat a cat with a dog product and so on);

- Some chemicals can be toxic both in the treated animals and in the humans performing the treatments. Use them according to strict label instructions;

- Debilitated animals should not be bathed in certain insecticides (read labels);

- Be careful - some lice products can not be used on pregnant or lactating animals;

- Owners and farmers (livestock producers) are advised to take appropriate safety precautions when using insecticidal chemicals (i.e. only use the products in a well-ventilated place; wear gloves, protective clothing and eye-protection when applying the products; consider wearing breathing apparatus when using the products, especially if they are aerosolized products and so on);

- Owners and farmers (livestock producers) are also advised to be aware of and to take appropriate environmental precautions when using insecticide products (i.e. make sure there is no risk of any pesticide washing into waterways or groundwater supplies or sensitive ecosystems and so on).

- Be careful - Some of these products can not be used in animals producing meat, milk or wool for human consumption and, if they are, strict withholding periods may need to be observed;

- Be careful - Some of the active ingredients used in certain lice treatments (e.g. diazinon) may be illegal or banned in certain countries because of toxicity and food-chain-accumulation concerns.

- Be careful - Some of these ingredients are not allowed to be used on animals whose products are to be exported to certain countries (e.g. EU - European Union countries);

- Be careful - Some insecticides can damage a farm's organic certification;

- VITAL - retreat all lice treated animals within 10-14 days of the first treatment.

Author's note: There are a lot of products on the market that kill lice. These contain

all manner of insecticide ingredients, including: permethrins, pyrethrins, insect growth inhibitors, organophosphates, carbamates, rotenone, piperonyl and others. I have not named specific ingredients in this section because this lice life cycle page is about the general principles of treating

lice according to the lessons of the lice life cycle. For specifics on lice treatments in different

animal species, see our

lice pictures page. Section 5 has info on specific lice therapies in different animals.

2) Retreat all lice-treated animals within 10-14 days of the first treatment to kill any newly-hatched nymph stages.

3) Treating the environment and any fomites with insecticide - is it needed?:

As mentioned in the previous section on lice prevention, because the main lice population

is located predominantly on the bodies of the host animals and not in the environment, lice treatment tends to be targeted on the host animals themselves and not on the

environment or fomites surrounding those animals. Lice that make it into the environment generally die in the absence of hosts.

To completely ignore the host animal's surrounding environment and such important lice-carrying fomites as infected brushes, beds, blankets, rugs and travel boxes, however, would be folly and would pose the risk of exposing "clean" or freshly-treated animals to important sources of lice reinfestation. Bedding, grooming gear, tack and the like can be important sources of lice reinfestation and should not be forgotten. Consequently, treatment of the lice infected environment and also any infested fomites (beds, rugs, brushes and so on) may be important to the control of lice infestation and should be considered. Many of the insecticidal products (sprays, powders, washes and so on), which are used to treat lice on host animals, can also be applied to the animal's environment and also to any infected fomites (combs, brushes etc) to treat lice that are lurking in these off-host areas.

Please be aware, however, that applying such chemical products to the environment in general can pose a poison risk to the environment, soil and waterways and, in turn,

pose a great risk of insecticide residue toxicity to animals and people and vegetation in the area. Read the product labels to be aware of any environmental risks and toxicity

risks inherent in applying such products to the environment. Also be aware that simple

depopulation of an area (free of hosts) and time (up to 2 months) can be enough to remove environmental

lice reservoirs from yards, paddocks, runs, cages, aviaries and other fomites without the need for

harmful chemicals.

Preventing fomite-to-host lice transmission, especially if fomites or the environment are infested:

- Clean brushes and combs thoroughly before using them on a new animal (no shed hairs should be visible in the teeth/bristles of the brushes and combs);

- Brushes and combs used on louse infested animals should be treated with an effective insecticide louse killer and thoroughly rinsed and cleaned of all hairs before being used on any other animals. Resting the items for 3-4 weeks

before reuse (or resting them for 2 weeks and retreating them with insecticide, where practical and safe) is also advised;

- Don't share bedding, blankets or rugs between animals (especially if the animals' background and louse status is unknown);

- Clean bedding, blankets or rugs thoroughly before using them on a new animal (no shed hairs should be visible). Hot machine washing and steam cleaning can be useful here to ensure cleanliness (ideally bedding and the like should never be shared between different animals);

- Bedding, blankets or rugs used on louse infested animals should be treated with an effective insecticide louse killer and thoroughly rinsed and cleaned of all hairs before being used on any other animals. Disposable lice-affected bedding (e.g. old towels) should be thrown away after use. Resting the items for 3-4 weeks

before reuse (or resting them for 2 weeks and retreating them with insecticide, where practical and safe) is also advised.

- Clean shearing equipment thoroughly between animals in a flock (no shed hairs should be visible);

- Avoid shearing lice infected animals, particularly if there is a chance of non-infected animals being exposed to the same equipment (note that shearing of lice infested animals may be needed before certain

lice treatments can be applied);

- If possible, depopulate (remove all hosts from) yards, aviaries, chicken-coops, stalls, runs, cages, kennels and paddocks that have had lice-infected animals in them for at least 1 month (2 months to be safe). This host-free timespan will allow live lice to die and any eggs to hatch out and die, such that the site is no longer lice-infected. Widespread disinfecting with insecticide chemicals is possible for some kinds

of infected enclosures (e.g. aviaries, cages, runs, kennels), but it is not very safe for animals and personnel.

Widespread insecticide use should be avoided on large paddocks or yards due to the environmental impacts.

To go from this life cycle of lice page to the Pet Informed Home Page, click here.

To go from this life cycle of lice page to the lice pictures page, click here.

To go from this life cycle of lice page to the Pet Informed Home Page, click here.

To go from this life cycle of lice page to the lice pictures page, click here.

Lice Life Cycle References and Suggested Readings:

Lice Life Cycle References and Suggested Readings:

1) Arthropods. In Bowman DD, Lynn RC, Eberhard ML editors: Parasitology for Veterinarians, USA, 2003, Elsevier Science.

2) Phylum Arthropoda. In Hobbs RP, Thompson ARC, Lymbery AJ: Parasitology, Perth, 1999, Murdoch University.

Pet Informed is not in any way affiliated with any of the companies whose products

appear in images or information contained within this lice life cycle article. Any images, taken by Pet Informed, are only used in order to illustrate certain points being made in the lice life cycle article. Pet Informed receives no commercial or reputational benefit from any of these companies

for mentioning their products and can not make any guarantees or claims, either positive or negative, about these companies' products, customer service or business practices. Pet Informed can not and will not take any responsibility for any: death (human or animal), damage, illness (human or animal), injury or loss of reputation and business or production losses (e.g. meat, milk, wool) or

loss of organic or export accreditation or for any environmental damage that occurs should you choose to use one of the mentioned products on your pets, poultry or livestock (commercial or otherwise). Do your homework and research all such louse products carefully before using any lice products on your animals

or their environments.

Copyright July 31, 2009, Dr. O'Meara, www.pet-informed-veterinary-advice-online.com.

All rights reserved, protected under Australian copyright. No images or graphics on this Pet Informed website may be used without written permission of their owner, Dr. O'Meara.

Please note: the aforementioned lice prevention, lice control and lice treatment

guidelines and information on the lice life cycle are general information and recommendations only. The lice life cycle and lice control information provided is based on published information and on recommendations made available from the drug companies themselves; relevant veterinary literature

and publications and my own experience as a practicing veterinarian.

The advice given is appropriate to the vast majority of pet and large animal owners, however, given

the large range of lice medication types and louse prevention and control protocols now available, owners

and producers should take it upon themselves to ask their own veterinarian what treatment and louse prevention schedules s/he is using so as

to be certain what to do. Owners with specific circumstances (high louse infestation

burdens in their pet's environment, pregnant bitches and queens, very young puppies and kittens,

louse infested rodents, louse affected animal breeding facilities, louse affected

livestock and poultry producers, multiple-animal and intensive production environments, animals on immune-suppressant medicines, animals with immunosuppressant diseases or conditions, owners of sick and

debilitated animals, owners producing animals for meat, milk and hides, owners producing meat, milk, lambs/kids and fleece for export, owners producing meat, milk, lambs/kids and fleece for organic

accreditation and so on) should ask their veterinarian or stock supplier what the safest and most effective lice protocol is for their situation.

Any dose rates mentioned on this lice life cycle page should be confirmed by a vet. Dosing rates for common

drugs are being changed and updated all the time (e.g. as new research comes in and as drug

formulations change) and information here (on this lice life cycle page) may not remain current for long. What's more, although we try very hard to maintain the accuracy of our information, typos and oversights do occur. Please check with your vet before dosing any pet any medication or drug.

Please note: the scientific louse names mentioned in this lice life cycle article are only current as

of the date of this web-page's copyright date. Parasite scientific names are constantly being

reviewed and changed as new scientific information becomes available and names that are current

now may alter in the future.

Lice infestation is one of the great banes in life for many pet, poultry and livestock owners.

Lice infestation is one of the great banes in life for many pet, poultry and livestock owners.