The Hydatid Tapeworm Life Cycle Echinococcus granulosus and multilocularis

Hydatid tapeworms (Echinococcus granulosus and Echinococcus multilocularis) are highly dangerous tapeworm species of dogs, cats and certain wild carnivores (e.g. foxes, coyotes), which occasionally make their way into the bodies of humans, producing "hydatid disease" - a condition (also called 'echinococcosis') characterised by the appearance of large, expansive, life-threatening hydatid cysts (larval tapeworms) within the internal organs of the infested person.

Hydatid tapeworms (Echinococcus granulosus and Echinococcus multilocularis) are highly dangerous tapeworm species of dogs, cats and certain wild carnivores (e.g. foxes, coyotes), which occasionally make their way into the bodies of humans, producing "hydatid disease" - a condition (also called 'echinococcosis') characterised by the appearance of large, expansive, life-threatening hydatid cysts (larval tapeworms) within the internal organs of the infested person.

The disease significance of the hydatid tapeworm parasite:

These cestode parasites do not usually cause major disease problems for their definitive

hosts (see hydatid tapeworm life cycle diagram below for info on definitive hosts)

because they are very small in size compared to most other parasitic tapeworm species. Adult Echinococcus tapeworms are only a couple of segments long (<1cm long) and, as a consequence of this, they do not cause major disease

issues like intestinal blockage and excessive competition with the definitive host animal for nutrients. Hydatid tapeworms do, however, produce major disease concerns when their large larval cysts (hydatid cysts) turn up in the organs of intermediate host animals (livestock animals, wild herbivores, wild omnivores, various rodents) and, most worryingly, people.

Hydatid cysts (larval tapeworms) develop as expanding, space-occupying lesions in vital organs like the brain, liver, lungs and kidneys. The cysts grow and expand sizably, crowding out and compressing the cells that

make up the organs they have invaded. This eventually leads to the dysfunction of these internal organs

as vital structures get compressed (e.g. blood vessels that supply nutrients and life to organs may be closed off; drainage structures like biliary ducts and ureters, which help to draw fluid from various organs, may be compressed

shut; airways that provide oxygen to the lungs may become squashed by the enlarging cysts and so on) and even destroyed (e.g. compression of organ cells by an expanding cystic mass can result in their death from compression injury - termed "pressure atrophy"). If not diagnosed and treated promptly, the hydatid-induced organ damage (e.g. brain damage, lung damage) can become so severe that the animal or

person with the hydatid disease will become permanently compromised or even die.

In humans, the devastation that hydatid disease causes for the affected individual, community and family goes without saying. The medical costs of treating and curing the condition may also be high.

In animals, the losses can also be significant. Animals that succumb to the disease no doubt suffer in the process (i.e. hydatid infection is an animal welfare issue). Endangered wildlife can die from hydatid disease - losses that could be very significant in already-population-depleted species. From a livestock production point of view, the financial loss to commercial meat producers can also

be significant since hydatid infested meat and offal will most likely be rejected from the commercial food chain (i.e. won't be able to be sold).

Overall, there are significant human health, animal health, animal welfare, wildlife

preservation and primary producer benefits to be gained from controlling and preventing this horrible parasitic disease. Such control and prevention requires a knowledge of the hydatid tapeworm life cycle. Breaking the lifecycle is key to eradicating the parasite.

This hydatid tapeworm life cycle page contains a detailed, but simple-to-understand explanation of the

complete hydatid tapeworm life cycle. It comes complete with a full hydatid life cycle diagram for ease of understanding. Explanation of the cycle is included, along with advice on how the

Echinococcus tapeworm lifecycle can be used as an aid in the control and treatment and prevention of hydatid disease in definitive

host and, most vitally, intermediate host populations.

The Hydatid Tapeworm Life Cycle - Contents:

1) The hydatid tapeworm life cycle diagram - a complete step-by-step diagram of canine Echinococcus granulosus tapeworm infestation and its transmission via intermediate livestock and wild animal hosts. Human infestation

and the development of unilocular hydatid disease is discussed.

2) Echinococcus multilocularis - the lesser known hydatid tapeworm (responsible for producing alveolar hydatid disease). 3) Treatment and prevention of hydatid tapeworm infestations in definitive host dogs.

4) Some basics on human hydatid infestation and prevention of hydatid disease in people.

The Hydatid Tapeworm Life Cycle - Contents:

1) The hydatid tapeworm life cycle diagram - a complete step-by-step diagram of canine Echinococcus granulosus tapeworm infestation and its transmission via intermediate livestock and wild animal hosts. Human infestation

and the development of unilocular hydatid disease is discussed.

2) Echinococcus multilocularis - the lesser known hydatid tapeworm (responsible for producing alveolar hydatid disease). 3) Treatment and prevention of hydatid tapeworm infestations in definitive host dogs.

4) Some basics on human hydatid infestation and prevention of hydatid disease in people.

1) The Hydatid Tapeworm Life Cycle Diagram:

1) The Hydatid Tapeworm Life Cycle Diagram:

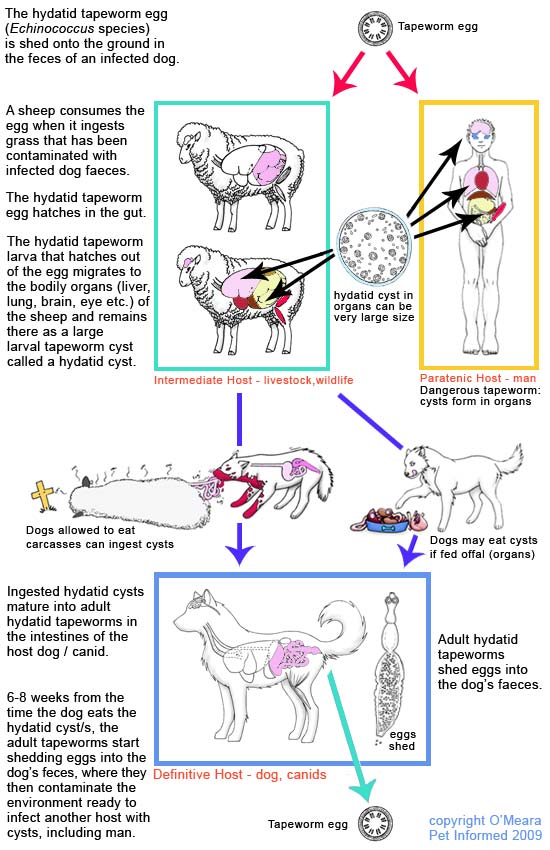

Hydatid tapeworm life cycle diagram:

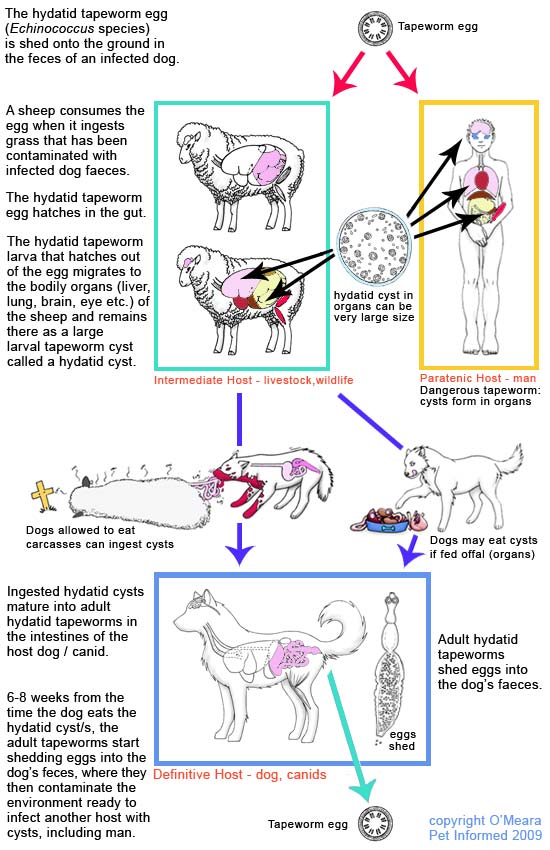

Hydatid tapeworm life cycle diagram: This is a diagram of the life cycle of the

Echinococcus granulosus hydatid tapeworm.

The diagram shows the complete cycle of a hydatid tapeworm's existence - from egg to adult tapeworm to egg again (with the next generation of tapeworm eggs) - within the bodies of two very different, yet both equally essential, host animal species:

1. the intermediate host animal - usually a livestock animal species (e.g. sheep, cow, goat, horse, donkey, pig, camel) or an omnivorous or herbivorous wild animal species (e.g. marsupial, wild cattle, wild sheep, wild goat, deer, moose, caribou) and

2. the definitive host animal - usually a wild or domesticated carnivore, generally of the canine variety (e.g. dog, wolf, coyote, wild dog, lion).

You'll note that the human in the diagram has been labeled "

paratenic host." A paratenic host is

essentially the same as an intermediate host except that, unlike the intermediate host, the paratenic

host is not a typical, essential host in the parasite's life cycle. A paratenic host is essentially

an 'accidental' host - not a normal part of the parasite's usual life cycle. The hydatid tapeworm could carry on its

life cycle quite happily in the absence of people. In fact, human infestation with hydatids is actually considered to be

highly

undesirable as far as the hydatid tapeworm life cycle is concerned. If a hydatid cyst does find its way into a person, it will most likely

never get the chance to mature into an adult tapeworm from there (because it is unlikely that the human, even in death, will be consumed by a definitive host carnivore such as a dog). The tapeworm life cycle will, therefore, not be completed (a

loss as far as the hydatid parasite is concerned).

Adult

Adult hydatid tapeworms live and feed in the small intestines of such host animals as the dog (pictured in diagram) and other wild canids including the wolf, coyote and dingo. These carnivorous host animals are termed

definitive hosts with regard to the hydatid tapeworm life cycle because they are

the hosts that the parasitic tapeworm was intended for and that the tapeworm organism reaches adulthood and sexual maturity in.

The bodies of most adult tapeworm species (e.g.

Spirometra, Taenia, Dipylidium, Anoplocephala and so on) are made of up many hundreds of individual segments, termed

proglottids.

These proglottids increase in size and maturity as you travel down the tapeworm's body

from the head (scolex) towards the tail. At the tail end, the proglottid segments are large and sexually mature with hundreds of fertilized eggs contained inside of them. These tapeworm eggs are excreted into the definitive host animal's environment (ready for the intermediate host to come along and consume)

still contained within their protective proglottid casing. Basically, the entire proglottid segment (mature, egg-bearing proglottid segment located towards the tail-end of the tapeworm parasite), eggs and all, exits the definitive host animal's body via the animal's anus. The gravid segment either physically crawls from the anus of the host animal by contracting its muscles and creeping along or it is voided passively in the animal's stools as the pet defecates.

You can read more about tapeworm proglottids in our

flea tapeworm page.

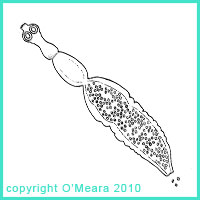

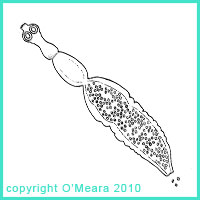

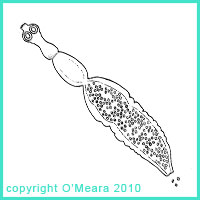

In the case of

Echinococcus, the above paragraph about other tapeworm species does not hold true. Hydatid tapeworms are

very tiny tapeworms, less than 1cm long, which are comprised of only about 3-5 proglottid segments in total (I have drawn a simplified diagram of a hydatid tapeworm to the right). Once the hydatid tapeworm has attained its adult size, the hydatid tapeworm stops growing and does not continue to elongate like other tapeworm species do (i.e.

Echinococcus never achieves the massive length, size and proglottid numbers that such big tapeworms as

Taenia and

Spirometra do). Of the proglottid

segments making up the hydatid worm's body, only the rearmost segment (the large tail segment) actually produces eggs (tiny round dots in diagram). This mature end segment is not shed into the external environment along with the eggs, as occurs in most other tapeworm species. The rear egg-brooding segment merely releases the eggs into the host animal's feces, allowing the feces to transfer these ova into

the outside world (ready for the intermediate host to come along and consume).

Similar to other tapeworms, the hydatid tapeworm is a hermaphrodite organism (bearing both male and female sex structures).

The terminal, egg-bearing segment is essentially an individual egg-producing reproductive factory. The last

proglottid segment has its own testicular-type organ structures (several) and its own uterine organ structure/s (for creating and maturing eggs) and is, therefore, quite capable of producing and fertilizing its own set of eggs, once mature.

An

intermediate host animal (usually a livestock animal, such as a sheep or cow, but sometimes a wild animal species, such as a kangaroo or moose) consumes the hydatid tapeworm eggs present in the environment. These

eggs are generally consumed in a pasture or forest-type environmental setting. The infested definitive host animal defecates

onto the pasture (e.g. pasture on a farm) or in the forest (e.g. bushland, national park setting) and, in doing

so, sheds infective tapeworm eggs into this environment. The organic feces break down, but the resistant

tapeworm eggs remain in the environment, speckled invisibly across the grass. The intermediate host animal

consumes the tapeworm eggs, thereby becoming infested, by eating the contaminated pasture contained within this forest or

farmland setting.

When the intermediate host consumes the tapeworm egg/s, the tapeworm embryos contained inside of these eggs survive and hatch from their eggs within the intestines of the intermediate host animal. The tapeworm embryos migrate across

the intestinal wall and establish themselves within the organs of the intermediate host animal. Organs commonly chosen for this invasion include the liver, mesenteries, lungs

and brain, but any part of the body can, theoretically, be infested (e.g. bone marrow, muscle, eye). Once established in a site, the tapeworm embryos develop further into an intermediate larval tapeworm stage called a

hydatid cyst.

Note on terminology: an intermediate host animal (e.g. sheep, cow, kangaroo in this case) is a host

animal that the hydatid tapeworm parasite needs to infest if it is to be able to complete an essential part of its lifecycle. In this case, the hydatid tapeworm needs to infest an animal host (generally a herbivore or omnivore) if it is to hatch from the tapeworm egg and transform into a larval

hydatid cyst stage. The parasitic tape worm is

unable to reach adulthood and sexual maturity inside of an intermediate host animal and needs to later enter the body of a definitive host animal like a dog in order

to achieve sexual and reproductive maturity.

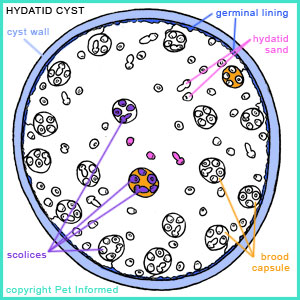

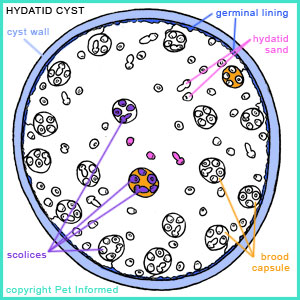

The hydatid cyst of

Echinococcus granulosus is a large, expanding, fluid-filled structure (see diagram - pale blue outer wall)

with a thin, almost see-through, outer wall (at surgery, it looks a bit like a colourless water-balloon). The inner lining (

"germinal lining" - darker blue layer on diagram) of the outer membrane of the hydatid cyst actively buds off small mini-cysts inside of itself.

These inner-cysts, called "brood capsules" (orange on diagram) are miniature replicas of the main hydatid cyst (i.e. tiny 'water balloons' contained within the large, main 'water balloon'). They may float about freely inside of the main cyst or they may remain attached to the inner germinal lining of the main cyst by a thin connective strand. These brood capsules generate within themselves miniature larval tapeworms (termed 'scolices or protoscolices). These tiny larval tapeworm forms (purple on diagram) are the individuals that become the adult tapeworms when the

hydatid cyst is consumed by the definitive host animal (dog). The brood capsules within

the main cyst body sometimes burst, releasing the tiny larval tapeworm protoscolices into

the main cyst structure (pink on diagram) - these sediment out with gravity, settling into the lower regions

of the main cyst as a grainy, tapeworm sediment termed 'hydatid sand'. It is also likely that

the germinal lining of the main hydatid cyst is able to produce and shed hydatid sand without the need

for a burst brood capsule (i.e. the cyst lining can make protoscolices directly while, at the same time, manufacturing brood capsules).

The hydatid cyst of

Echinococcus granulosus is termed a "unilocular cyst" because it

has one main expanding, non-invasive cyst body and keeps its brood capsules internalised

(i.e. the brood capsules and hydatid sand stay

within the main cyst body). This is different to the "alveolar hydatid cyst" structure of

Echinococcus multilocularis, which generates external

buds of its wall (daughter cysts) on the

outside of the main cyst structure, such that they spread aggressively through the intermediate host animal's internal tissues. See notes on

E. multilocularis, below.

Author's note: If the main wall of a hydatid cyst is inadvertently ruptured (e.g.

during surgical removal), the brood cysts and hydatid sand can spill out and disseminate throughout the animal's body.

This can result in other hydatid cysts establishing all through the intermediate host's tissues,

a condition (termed multiple hydatidosis) that is tricky to treat and often fatal. It is for this reason that humans

infested with hydatid cysts are generally treated with anthelminthec drugs (e.g. albendazole)

for many weeks prior to the onset of any surgery aimed at removing the hydatid cysts from the tissues. The drug sterilises and kills the protoscolices contained within the hydatid cyst, so that there

will be less risk of hydatid dissemination, should the surgeon inadvertently break the cyst and

spill out the hydatid sand.

Author's note: Curiously, hydatid cysts do not seem to grow as well in certain species

of intermediate host animal. The hydatid cysts of cattle are

sometimes sterile, forming large, cystic

cavities in the organs of the animal without the presence of brood capsules and protoscolices. These cysts look large and impressive, but are not infective to the definitive host animal. The hydatid cysts of sheep, on the other hand, are usually infective to the definitive host animal and are loaded

with hydatid sand protoscolices and brood capsules.

The unilocular hydatid cyst causes damage to the intermediate host animal's tissues as it grows.

The damage is generally in the form of pressure atrophy - the cyst crushes the tissue cells around it as it expands

in size, causing the cells of the infested organ to die off bit by bit. Sometimes the cyst

crushes a vital blood supply, killing the cells and organs supplied by that circulatory pathway. Sometimes

the cyst crushes other vital tubular structures like the gall bladder, ureter, bile duct

and bronchi, causing severe dysfunction of these conduits. Sometimes the cyst can leak small amounts

of fluid into the surrounding tissues, resulting in severe allergic reactions (the host immune

system attacking the fluid) and painful tissue inflammation of the area. Such aggressive inflammation (e.g. immune cells releasing chemicals that destroy and damage protein structures) can

badly injure the host tissues, even though the main aim was to destroy the foreign cyst-fluid. Should a large

cyst happen to rupture, the massive fluid release can result in a severe anaphylactic reaction

(the sudden death of the patient is quite possible should this occur).

The symptoms and consequences of this damage depends very much on the size and number of the cysts

present and on the organ location that the cysts have invaded. Because most organs

(not the brain) have a high degree of tissue redundancy (meaning that a lot of tissue can be lost before

symptoms of organ damage are present), a quite-sizeable population of small hydatid cysts may not produce any obvious symptoms in the intermediate host for a long time. The liver is a good example of this - several large hydatid cysts in the liver may not cause any signs of ill-health

(unless they happen to be positioned such that they squash a vital liver structure like the gall bladder

or common biliary duct). Lung hydatids may also present initially with minimal signs,

however, the animal will generally develop coughing, shortness of breath and wheezing

as the cyst/s expand. On the flip side, certain other organs can not take even the smallest tapeworm cyst

lightly. The brain is a classic example - even a very small hydatid cyst in the brain

can result in severe neurological deficits for the infested host.

Images of hydatid cysts in organs:

http://cal.vet.upenn.edu/projects/dxendopar/parasitepages/cestodes/e_granulosus.html

http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/DiseaseInfo/ImageDB/ECH/ECH_002.jpg

http://www.aafp.org/afp/2002/0901/afp20020901p817-f2.jpg - a nice renal hydatid cyst, which has been opened

up to show off the brood capsules contained within the main cyst body

The definitive host animal (dog or other canid) ingests the hydatid cyst stage of the hydatid tapeworm life cycle by consuming the hydatid-infested organs of an intermediate host animal that has become infested. The definitive host animal must eat an infective, fertile cyst, containing active

brood capsules and protoscolices, if it is to become infested with the adult hydatid tapeworm forms.

This sort of consumption is common in the wild, where wild canids (e.g. wolves, dingos)

feast on the fresh, warm offal of their freshly killed prey (e.g. moose, kangaroo). It can also occur

in the domestic domain, when farmers offer the innards of freshly-killed livestock to their dogs

or hunters allow their pets to snack on the results of their shooting trips (e.g. pig hunters and roo hunters

often feed their dogs on the raw meat and organs of the animals that they have killed).

When the definitive host animal consumes the tapeworm-cyst-infested intermediate host, the mini-tapeworm

protoscolices get released from the hydatid cyst brood capsules and enter the intestinal tract of the

definitive host carnivore. Here these protoscolices develop into final-stage adult tapeworms. They attach

to the wall of the canine's intestinal tract, grow to full size and start shedding eggs into

the droppings. The first adult tapeworm eggs start appearing in the animal's environment about 6-8 weeks after the hydatid-cyst-infested intermediate host animal was first ingested. Adult worms

can live in the definitive host animal for a period of 6 months to almost 2 years.

Thus the hydatid tapeworm life cycle continues ...

Author's note: The hydatid tapeworm life cycle tends to be most successful and prevalent

when definitive hosts and intermediate hosts live and feed in close proximity to one another

(which makes obvious sense). Strong hydatid tapeworm life cycles tend to establish in environments between animals

that have a natural host-prey relationship. For example, in Australia, a hydatid tapeworm

life cycle commonly exists in areas where dingos and kangaroos co-exist. The dingo defecates tapeworm

eggs onto the pasture, infesting the kangaroos with hydatid cysts that are later consumed by the dingo when

it hunts and consumes the kangaroos. Around the world, other host-prey relationships such as: moose-wolf relationships, lion-warthog relationships and coyote-deer relationships also keep the

hydatids cycling. It can be quite difficult to get rid of

Echinococcus granulosus tapeworms from an

environment where there is a strong sylvatic hydatid tapeworm life cycle in play

(i.e. a tapeworm life cycle that persists in wild animal populations completely away from the influence

of man or his dogs).

It is for this reason - the ability to maintain a strong definitive-host and intermediate-host

relationship (essential to the hydatid tapeworm life cycle) - that the majority of domestic animal

hydatid infestations occur in dogs that come from or have regular access to rural regions, farms and wild spaces (e.g. national parks with lots of wild animal intermediate hosts).

Dogs that spend lots of time in these environments, feeding on offal and carcasses (e.g. working dogs, herding dogs, hunting dogs, pig-dogs) are at greater risk of carrying hydatid tapeworms.

2) Echinococcus multilocularis - the lesser known hydatid tapeworm (responsible for producing alveolar hydatid disease).

Echinococcus multilocularis is an extremely nasty form of hydatid tapeworm that is endemic

to the North American continent (including USA, Canada and Alaska), New Zealand and parts of South America, Europe and Asia. Its life cycle is identical to that of Echinococcus granulosus in that

it requires both a definitive host animal and an intermediate host animal if it is to complete its life cycle successfully. The hosts favoured by Echinococcus multilocularis are slightly different to those of E. granulosus (e.g. the fox is the main host and small rodents, rather

than livestock animals, dominate as intermediate hosts for the condition), but the life cycle diagram is pretty much identical otherwise.

The definitive hosts - fox (common host), dog, cat, wild canid. The presence of the cat as a major definitive host also makes Echinococcus multilocularis different to E. granulosus. People

must remember to treat their cats for tapeworms in endemic regions.

The definitive hosts - fox (common host), dog, cat, wild canid. The presence of the cat as a major definitive host also makes Echinococcus multilocularis different to E. granulosus. People

must remember to treat their cats for tapeworms in endemic regions.

The intermediate hosts - usually small rodents (voles, mice and so on), but also livestock animals.

The main difference between Echinococcus granulosus and Echinococcus multilocularis

lies in the nature of their intermediate host hydatid cyst forms. As discussed previously, the hydatid

cyst of Echinococcus granulosus is a large, expanding, thicker-walled, unilocular cyst with all of the brood capsules and protoscolices contained within. It expands slowly, causing damage

by passive compression.

The hydatid cyst of Echinococcus multilocularis, in contrast, is thinner walled

and, instead of budding out its brood capsules and protoscolices internally, it aggressively extends bud-like fingers of cyst wall outwards into the surrounding host tissues, penetrating them and invading them. These bud-like extensions of cyst-wall (called daughter cysts) contain germinal tissue linings that produce protoscolices and small brood capsules just like the E. granulosus cyst lining does.

In some cases, pieces of cyst wall even break off and spread to other regions of the body to continue the cystic onslaught. Basically, the Echinococcus multilocularis hydatid cyst acts like a malignant cancer, aggressively

budding and expanding and invading into the host's tissues and destroying them in the process. Death

of the intermediate host is very likely if the parasite is not diagnosed and treated (removed)

promptly. The disease that results in the intermediate host from Echinococcus multilocularis

is called "alveolar hydatid disease" - named after the hundreds of interconnected cysts

that form, which look similar in appearance to the interlinked, air-exchange

structures of mammalian lungs (called alveoli).

Images of alveolar hydatid cysts in organs:

http://fullmal.hgc.jp/em/icons/Fig2.jpg

This is a lovely histopathology image of alveolar hydatid disease, showing the multiple

alveolar hydatid cysts invading into the host's tissue. Seven individual cystic buds are clearly

seen (large, open spaces surrounded by a dark pink cyst wall). Contained within these cyst walls are

many dark pink circular structures, which are the hydatid protoscolices in cross-section.

http://pathtalk.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/echinococcus-answer3.jpg

Another histopathology slide showing alveolar hydatid disease. The individual cystic buds have been labeled. The dark pink structures seen inside the cysts are sections through the protoscolices.

http://www.scielo.org.za/img/revistas/samj/v99n5part1/a11fig01.jpg

A bit confronting, this is an image of alveolar hydatid disease in a human patient. The hydatid cysts

are budding and expanding and their budding cysts (daughter cysts) spill from an incision in

this person's skin. The person had surgery to treat the condition. It shows the nasty, infiltrative nature of human hydatidosis very clearly.

Author's note: Thankfully, Echinococcus multilocularis infestation of humans is uncommon. This is partly because the larval cysts do not seem to favour our bodies and grow as well inside of us as

they do inside of their usual intermediate host animal species (this is not to say that these tapeworms are

not highly dangerous for us humans - many people who get alveolar hydatid disease die horribly). The rarity

of human infection is also because the hydatid tapeworm life cycle of Echinococcus multilocularis tends to take place in sylvatic (wild) animal

environments where humans seldom go. With the fox as the main definitive host, only humans who handle and trap foxes or enter fox environments are likely to get the parasite. Although dogs and cats can get the organism to pass

on to their owners, it is only the pets who feed on the correct intermediate hosts (e.g. voles)

and who are not dewormed regularly (most people know to worm their pets these days) who are likely to become

dangerous carriers. Hence human infestation is somewhat rare. Which is a very good thing!

3) Treatment and prevention of hydatid tapeworm infestations in definitive host dogs.

Adult hydatid tapeworms in dogs and cats can be eliminated from the animal's intestines

using tapeworm-specific anti-cestodal medications such as praziquantel. Praziquantel is the anticestodal drug most commonly included in commercially-available dog and cat 'all-wormers'. Basic information about praziquantel is contained below.

When an

adequate dose of an

appropriate* anti-tapeworm drug is administered to the definitive host animal, the tapeworms die and are voided in the host animal's feces (pet owners won't usually

notice these dead tapeworms in their animal's feces because they are so very small). This single treatment is usually curative, however, several doses may be needed to completely rid an animal of a very large hydatid tapeworm

burden (if a large tapeworm burden is suspected, the praziquantel can be repeated two-weekly for a couple of doses

to be sure of getting them all).

* not all tapeworm-killing drugs kill

Echinococcus species, so make sure you check that any tapeworm medication you give is appropriate for killing this nasty tapeworm species. Praziquantel

is a good choice for hydatid tapeworms and is easy to get. For other anti-tapeworm medication options,

see the notes at the bottom of this section to see whether or not they kill

Echinococcus.

Author's note: Be aware that most deworming medications (aside from some heartworm meds) do

not generally last very long in a treated-animal's system. When an all-wormer is given to a pet, the drugs work rapidly, killing off the adult worm parasites, before disappearing. The drugs do not hang around to protect the pet against subsequent worm infestations. This means that should

the pet continue to eat hydatid-cyst-infested offal in the days following

the deworming treatment, they will most likely become rapidly re-infested with adult hydatid tapeworms.

Following the ingestion of a cyst-infested intermediate host, a definitive host

dog or cat can have a reproductively-mature, egg-shedding adult tapeworm inside of its

intestine within

6-8 weeks. In high-transmission situations (e.g. a dog fed frequently on raw offal), a pet owner might need to repeat worm (tapeworm-treat) his dog or cat every 6 weeks to keep the adult tapeworm numbers under control!

Because 6-weekly worming may not be practical for some pet owners (owners often forget to give the medication

on time), the best option for the ongoing control of hydatid tapeworms is to:

a) give the animal regular tapeworming medications (as per the manufacturer's directions)

and

b) not allow the animal access to foods likely to contain hydatids (e.g. raw carcasses, raw offal).

Praziquantel.

Praziquantel is a powerful tapeworm-killing drug that is generally included in the vast majority

of commercially-available 'all-wormers' given to dogs and cats. It has a high margin of safety in dogs and cats

(and many other species) and exhibits very good activity against most of the major tapeworm species affecting our domestic pets (including: the common flea tapeworm - Dipylidium caninum; the hydatid

tapeworms - Echinococcus granulosus and E. multilocularis; the zipper worm - Spirometra

and the many varieties of Taenia tapeworm species). It is because of this excellent activity against such a wide range of pet tapeworm parasites that praziquantel tends to be favoured over

most other anti-tapeworm medications in the control of hydatid tapeworms in domestic household animals.

How it works:

Tapeworms are coated in protein molecules that shield them from being recognized and attacked by

the host animal's immune system. These protein molecules turn over and shed from the tapeworm's body surface

constantly. By the time the host's immune system recognizes and starts to attack one lot of tapeworm surface molecules, these have been shed from the tapeworm's 'skin', leaving the immune system with nothing recognisable to attack.

Praziquantel works by disrupting the surface integument of the worm such that the animal's immune system is capable of recognizing the tape worm as foreign and actively attacking it. Additionally, praziquantel

also works by massively increasing the influx of calcium ions into the tapeworm's body. This calcium overload causes

the worm's muscles to become over-stimulated such that the worm develops stiffness and rigidity. The rigid

tapeworm is unable to maintain its hold on the host's gut wall and is, consequently, voided from the animal's intestinal tract via the faeces.

Features of praziquantel:

- The treatment of choice for tapeworms in dogs and cats.

- Kills a wide range of cestode (tapeworm) species in people and animals.

- Kills Schistosoma - an important parasite of humans, which causes a terrible, often fatal, liver condition called bilharzia (common in third world countries).

- Also kills some forms of trematode (fluke) parasite in livestock animals.

- In very high doses, praziquantel also kills certain intermediate-stage, larval tapeworm forms. Unfortunately

for us humans, praziquantel does not kill hydatid tapeworm cysts. It is possible that praziquantel may actually

make alveolar hydatid disease worse in intermediate hosts like humans.

- Very effective at killing adult Dipylidium caninum flea tapeworms.

- Very effective at killing hydatid tapeworms.

- A dose of 2.5-5mg/kg is needed to kill Dipylidium. Most all-wormers contain 5mg/kg praziquantel, which is ample for killing this flea tapeworm.

- A dose of 5-10mg/kg is needed to kill hydatid tapeworms (Echinococcus species). The higher

dose range is recommended to kill juvenile forms of the worms in dogs. Most all-wormers contain 5mg/kg praziquantel, which is within the dose range for killing these nasty tapeworms, however, given how dangerous hydatid tapeworm infestations are to people, if I was a dog owner living in a high hydatid risk situation, I would probably err on the side of caution and give the higher dose (10mg/kg). The drug should be given 6-weekly to keep hydatids under full control.

- Some tapeworms like Spirometra and Diphyllobothrium erinacei require an intermediate dose range (7.5mg/kg) be given on 2 consecutive days.

- Many of the tapeworms and flukes afflicting livestock animals need high doses of praziquantel if they are to be cleared (in the order of 15-30mg/kg and higher).

- Praziquantel, given orally, absorbs into the animal's body rapidly, reaching many organs including the liver and brain (this systemic absorption is why praziquantel is effective against Schistosoma and certain larval tapeworm forms).

- Praziquantel has a wide safety margin and is difficult to overdose (dogs were tested on up to 180mg/kg orally with little side effect).

- Praziquantel is thought to be safe in pregnant and breeding animals (check with your vet).

- Some praziquantel-containing products advise not using praziquantel in puppies or kittens under 4 weeks of age.

NOTE - Please read our disclaimer before attempting to self-diagnose and dose your animals with

any drugs mentioned on these pages. Pet Informed is a general advice website only and mistakes can be

made - we always recommend that you double-check any of our information with your own vet.

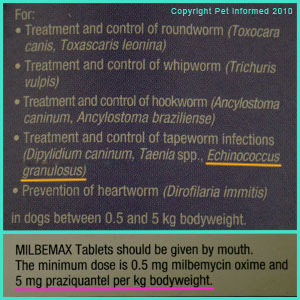

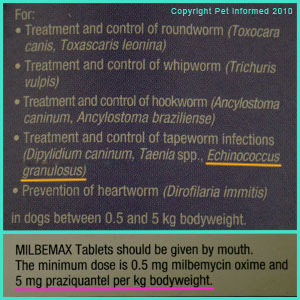

Hydatid tapeworm life cycle picture: These are photographs of the box-labels of a common dog and cat

all-wormer called Milbemax. You can see from the first image that the product contains praziquantel

(25mg of praziquantel per tablet - underlined in aqua). The second image shows the range of parasites that

the product kills. The hydatid tapeworm, Echinococcus granulosus (underlined in orange) is listed

as one of the parasites that this product kills. Also mentioned on the Milbemax box was the minimum recommended dose rate of praziquantel (underlined in pink) - it is listed as 5mg/kg.

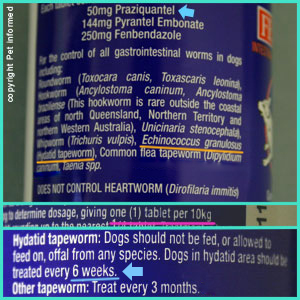

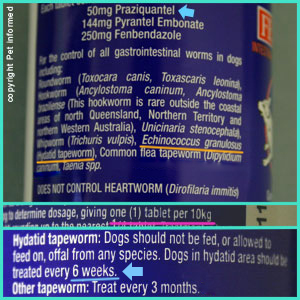

Hydatid tapeworm life cycle picture: These are photographs of the bottle-labels of a common dog

all-wormer called Fenpral. The first image is a picture of the product bottle (dog version of Fenpral). The second image shows that the product contains 50mg of praziquantel per tablet (blue arrow). The image shows the range of parasites that

the product kills. The hydatid tapeworm, Echinococcus granulosus (underlined in orange) is listed

as one of the parasites that this product kills. Also mentioned on the Fenpral bottle is the minimum recommended dose rate of praziquantel (underlined in pink) - it is listed as being 1 tablet per 10kg of

bodyweight. Given that a single tablet contains 50mg of praziquantel, this must mean that the

minimum dose rate for praziquantel is, again, 5mg/kg (i.e. a 10kg dog gets 50mg so a 1kg dog must get 5mg). The label also recommends that the drug be given every 6 weeks for hydatid tapeworm control. Most vets will

recommend this.

Other Anti-Cestodal Drugs.

Aside from praziquantel, there are other anti-cestodal drugs out there that have some activity against many of the parasitic tapeworms, including Echinococcus, infesting dogs and cats. I will not make huge mention of them, aside from the basic points below, because many of them are going out of fashion, many are hard to get, most have only a very narrow range of tapeworm activity, many don't

kill hydatids and some have significantly toxic side effects when used in domestic animals. I would not recommend using any of the

below-mentioned drugs to treat hydatid tapeworms in domestic pets (especially dogs and cats) if you have access to

praziquantel (see your vet). Praziquantel is the best as far as I can tell.

Niclosamide:

Has been used on tapeworms in dogs and cats.

Good activity against Taenia. Variable activity against Dipylidium, but unreliable against

Echinococcus (not reliable for breaking the hydatid tapeworm life cycle). Not satisfactory for

Echinococcus prevention.

Minimal absorption from the intestinal tract and toxicity is low (when used orally).

Must be given on an empty stomach.

Bunamidine hydrochloride:

Has been used on tapeworms in dogs and cats.

Good activity against Taenia. Fair to good activity against Echinococcus, but variable activity against

Dipylidium (not reliable for breaking the flea tapeworm life cycle).

Must be given on an empty stomach.

Has been known to have significant toxic side effects, including the death of pets.

Dichlorophene:

Has been used on tapeworms in dogs and cats.

Good activity against Taenia. Fair to good activity against Dipylidium, but unreliable against

Echinococcus (not reliable for breaking the hydatid tapeworm life cycle).

Minimal absorption from the intestinal tract, so toxicity is thought to be low (when used orally).

Hexachlorophene:

Mainly used to kill tapeworms and flukes in livestock animals, not domestic pets.

Good activity against Taenia and Echinococcus.

Tests on dogs have found that this drug can have significant toxic side effects in this species (cats unknown).

Toxicity concerns make it unfavourable for hydatid control.

Bithionol:

Has been used on tapeworms in dogs and cats and many other animal species.

Good activity against Taenia, but variable to low activity against

Dipylidium (not reliable for breaking the flea tapeworm life cycle).

Has been known to have toxic side effects in domestic pets (vomiting, diarrhea), but for the most part is

well-tolerated by dogs and cats.

Nitroscanate:

Apparently effective at killing hydatid tapeworms in dogs.

I can not vouch for its safety.

Epsiprantel:

Apparently effective at killing hydatid tapeworms in dogs (7.5mg/kg).

I can not vouch for its safety.

Benzimidazole drugs (Mebendazole, Fenbendazole and so on):

Many types of benzimidazole drugs have been studied in order to assess their effects against tapeworms in dogs and cats.

Most of them show good activity against Taenia and some even show good activity against Echinococcus, but none of them

is any good for treating Dipylidium (i.e. not reliable for breaking the flea tapeworm life cycle).

Benzimidazoles have been known to have significant toxic side effects in dogs and cats and other species.

Benzimidazoles are sometimes used to sterilise hydatid cysts in intermediate host animals prior to their surgical removal.

NOTE - Please read our disclaimer before attempting to self-diagnose and dose your animals with

any drugs mentioned on these pages. Pet Informed is a general advice website only and mistakes can be

made - we always recommend that you double-check any of our information with your own vet.

4) Some basics on human hydatid infestation and prevention of hydatid disease:

The prevention of human hydatid disease involves being aware of the hydatid tapeworm

life cycle and taking appropriate steps to prevent any chance of ingesting

the eggs from definitive host animal sources. This is particularly essential for humans

living in high hydatid-risk zones (e.g. New Zealand, Tasmania) where the numbers of infected

carrier animals (dogs, wild carnivores) are likely to be higher.

Preventing hydatids from your pets:

Worm your pet regularly - dogs and cats (cats - E. multilocularis) should be wormed

with the correct dose of an appropriate all-wormer tablet (e.g. praziquantel at 10mg/kg) every

6 weeks. This is particularly essential in high hydatid risk areas and in situations where the consumption

of infested offal (e.g. farms, large properties) by wandering pets is highly likely. Animals that are wormed

regularly (6-weekly) should not get adult tapeworms that can pose a risk to their owners.

Do not let your pet consume offal, especially raw, non-human-grade offal - hydatids infest

dogs and cats (definitive hosts) through the consumption of cyst-bearing offal (internal organs). Making sure that pets can not access such offal is important to keeping them free of hydatids. Don't let pets wander alone into places

(e.g. forest, bushland, open farmland) where carcasses are likely to be found and eaten. Don't let

pets hunt and consume live prey. Don't feed the results of hunting trips (e.g. killed kangaroos, killed deer, killed pigs)

to the dogs (particularly not the organ parts - although never guaranteed to be 100% free of cysts, leg meat is safer to give if you are planning on feeding the hunted meat to the dogs).

Also, if you do happen to see clear cysts in any offal - do not touch them, do not cut them and definitely do not feed them to the pets.

If you do need to feed offal, make sure it is human grade and that it is well-cooked - human grade

offal (e.g. liver, kidneys) is designed for human consumption and should be free of cysts. Cooking

offal at high temperatures for long periods should kill any hydatids if they should be present.

Practice good hygiene around your pets - always wash your hands when you have handled a pet

and never let the pet lick your face or share your food and plates. A dog with hydatids can lick

its bottom or eat its droppings, resulting in hydatid eggs entering its mouth. These infective eggs can

then be transferred onto the human's plate or mouth by the dog through plate-licking or face-licking activities.

Dogs and cats licking their coats can put eggs all through their coats, which the human can get onto his/her

hands through routine patting and handling. The human who does not wash his hands after handling the infested animal can catch the tapeworms if s/he uses those hands to eat food.

Be aware of the risk of animal feces entering the food chain - people should not let

their dogs or cats have access to garden vegetable patches. The animals can defecate in the garden, resulting

in hydatid eggs dropping onto the plants that the human is intending to consume.

Be extra-hygienic if handling dog feces - wear gloves to pick up droppings and wash your hands well afterwards.

Don't eat dog intestines - although not an issue where I come from, some cultures do like

to partake in the consumption of dogs and their offal. Undercooked dog intestines (especially from dogs of unknown worming status) could carry adult hydatid tapeworms and their eggs, which could infest the diner.

Preventing hydatids from wild animal hosts:

Be cautious about keeping wild carnivores as pets or allowing them access to the home environment - they may

be carrying hydatid tapeworms (particularly the extra-nasty alveolar form) into your environment. Foxes in particular can be high-risk in this regard. Certainly exercise extreme standards of hygiene when handling such animals.

Be aware of the risk of animal feces entering the food chain - people should not let

wild animal carnivores have access to garden vegetable patches. The animals can defecate in the garden, resulting

in hydatid eggs dropping onto the plants that the human is intending to consume. Humans should very carefully wash

all food (particularly uncooked food like fruit) before consuming it.

Exercise caution when exploring wild animal dens (e.g. fox dens) - places where infested animals

eat and sleep are generally loaded with tapeworm eggs. They drop from the animal's coat and drop from the feces. Protective clothing should be worn and extreme levels of hygiene maintained by anyone

intending to enter such places, particularly in highly-endemic areas. Children should not be permitted

to play in such areas (as their hygiene tends to be less) or go under the house (wild animals like to hide under houses, making

tapeworm egg numbers likely to be large in these regions).

Make sure children exercise good hygiene after playing in sand pits - sandpits are handy

toilet bowls for animals (e.g. cats) that like to bury their stools. The stools can carry eggs

into the sand pit, where the child can become infested during play.

Make sure to exercise good hygiene if handling potential hosts in a hunting setting - the hunting of foxes, cats

and wild dogs is common in many countries (Australia included). Shot animals are often handled by

the hunter - placed onto trucks or hung on fences. This handling could result in hydatid eggs

coating the hands of the hunter (with poor hygiene, it is possible for the hunter to inadvertently

consume the eggs and become infested with hydatids). Similar hygiene should also be exercised

by people who handle such animals for research purposes (e.g. people tagging animals).

Be careful performing surgeries or autopsies on possibly-infested intermediate hosts - it is possible for a doctor or vet performing a post-mortem or surgery on an infested intermediate host

to become infested with hydatids if s/he cuts into a hydatid cyst and gets sprayed in the eyes or mouth

with the hydatid fluid (which contains hydatid sand).

5) Your hydatid tapeworm life cycle links:

To go from this hydatid tapeworm life cycle page to the Pet Informed Home Page, click here.

Hydatid Tapeworm Life Cycle References and Suggested Readings:

1) Helminths. In Bowman DD, Lynn RC, Eberhard ML editors: Parasitology for Veterinarians, USA, 2003, Elsevier Science.

2) Phylum Platyhelminthes. In Hobbs RP, Thompson ARC, Lymbery AJ: Parasitology, Perth, 1999, Murdoch University.

3) Tapeworms. In Schmidt GD, Roberts LS: Foundations of Parasitology, 6th ed., Singapore, 2000, McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

4) Cestoidea: Form Function and Classification of the Tapeworms. In Schmidt GD, Roberts LS: Foundations of Parasitology, 6th ed., Singapore, 2000, McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

5) Roberson EL, Anticestodal and Antitrematodal Drugs. In Booth NH, Mc Donald LE: Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 6th ed., Iowa, 1988, Iowa State University Press.

Pet Informed is not in any way affiliated with any of the companies whose products

appear in images or information contained within this hydatid tapeworm life cycle article or our related articles. Any images or mentions, made by Pet Informed, are only used in order to illustrate certain points being made in the article. Pet Informed receives no commercial or reputational benefit from any companies

for mentioning their products and can not make any guarantees or claims, either positive or negative, about these companies' products, customer service or business practices. Pet Informed can not and will not take any responsibility for any death, damage, illness, injury or loss of reputation and business

or for any environmental damage that occurs should you choose to use one of the mentioned products on your pets, poultry or livestock (commercial or otherwise) or indoors or outdoors environments. Do your homework and research all tapeworm products carefully before using any tapeworm treatment products on your animals or their environments.

Copyright May 8, 2010, Dr. O'Meara BVSc (Hon), www.pet-informed-veterinary-advice-online.com.

All images, both photographic and drawn, contained on this site are the property of Dr. O'Meara and are protected under copyright. They can not be used or reproduced without my written permission.

Milbemax is a registered trademark of Novartis Animal Health Australasia Pty Ltd.

Fenpral Intestinal Wormer for Dogs is a registered trademark of Arkolette Pty Ltd / Riverside Veterinary Products.

Please note: the aforementioned hydatid tapeworm prevention, hydatid tapeworm control and hydatid tapeworm

treatment guidelines and information on the hydatid tapeworm life cycle are general information and recommendations only. The information provided is based on published information and on relevant veterinary literature and publications and my own experience as a practicing veterinarian.

The advice given is appropriate to the vast majority of pet owners, however, given

the large range of tapeworm varieties out there and the large range of tapeworm medication types and tapeworm prevention and control protocols now available, owners should take it upon themselves to ask their own veterinarian what treatment and tapeworm prevention schedules s/he is using so as to be certain what to do. Owners with specific circumstances (e.g. high and repeated hydatid tapeworm infestation burdens in their pet; hunting dogs; farm dogs; working dogs; herding dogs; pregnant bitches and queens; very young puppies and kittens; people in highly-endemic regions;

livestock and poultry producers; multiple-dog and cat environments;

animals on immune-suppressant medicines; animals with immunosuppressant diseases or conditions; owners of sick and

debilitated animals etc. etc.) should ask their vet what the safest and most effective hydatid tapeworm control protocol is for their situation.

Please note: the scientific tapeworm names mentioned in this hydatid tapeworm life cycle article are only current as

of the date of this web-page's copyright date and the dates of my references. Parasite scientific names are constantly being reviewed and changed as new scientific information becomes available and names that are current now may alter in the future.

Adult hydatid tapeworms live and feed in the small intestines of such host animals as the dog (pictured in diagram) and other wild canids including the wolf, coyote and dingo. These carnivorous host animals are termed definitive hosts with regard to the hydatid tapeworm life cycle because they are the hosts that the parasitic tapeworm was intended for and that the tapeworm organism reaches adulthood and sexual maturity in.

Adult hydatid tapeworms live and feed in the small intestines of such host animals as the dog (pictured in diagram) and other wild canids including the wolf, coyote and dingo. These carnivorous host animals are termed definitive hosts with regard to the hydatid tapeworm life cycle because they are the hosts that the parasitic tapeworm was intended for and that the tapeworm organism reaches adulthood and sexual maturity in.  In the case of Echinococcus, the above paragraph about other tapeworm species does not hold true. Hydatid tapeworms are

very tiny tapeworms, less than 1cm long, which are comprised of only about 3-5 proglottid segments in total (I have drawn a simplified diagram of a hydatid tapeworm to the right). Once the hydatid tapeworm has attained its adult size, the hydatid tapeworm stops growing and does not continue to elongate like other tapeworm species do (i.e. Echinococcus never achieves the massive length, size and proglottid numbers that such big tapeworms as Taenia and Spirometra do). Of the proglottid

segments making up the hydatid worm's body, only the rearmost segment (the large tail segment) actually produces eggs (tiny round dots in diagram). This mature end segment is not shed into the external environment along with the eggs, as occurs in most other tapeworm species. The rear egg-brooding segment merely releases the eggs into the host animal's feces, allowing the feces to transfer these ova into

the outside world (ready for the intermediate host to come along and consume).

In the case of Echinococcus, the above paragraph about other tapeworm species does not hold true. Hydatid tapeworms are

very tiny tapeworms, less than 1cm long, which are comprised of only about 3-5 proglottid segments in total (I have drawn a simplified diagram of a hydatid tapeworm to the right). Once the hydatid tapeworm has attained its adult size, the hydatid tapeworm stops growing and does not continue to elongate like other tapeworm species do (i.e. Echinococcus never achieves the massive length, size and proglottid numbers that such big tapeworms as Taenia and Spirometra do). Of the proglottid

segments making up the hydatid worm's body, only the rearmost segment (the large tail segment) actually produces eggs (tiny round dots in diagram). This mature end segment is not shed into the external environment along with the eggs, as occurs in most other tapeworm species. The rear egg-brooding segment merely releases the eggs into the host animal's feces, allowing the feces to transfer these ova into

the outside world (ready for the intermediate host to come along and consume).  An intermediate host animal (usually a livestock animal, such as a sheep or cow, but sometimes a wild animal species, such as a kangaroo or moose) consumes the hydatid tapeworm eggs present in the environment. These

eggs are generally consumed in a pasture or forest-type environmental setting. The infested definitive host animal defecates

onto the pasture (e.g. pasture on a farm) or in the forest (e.g. bushland, national park setting) and, in doing

so, sheds infective tapeworm eggs into this environment. The organic feces break down, but the resistant

tapeworm eggs remain in the environment, speckled invisibly across the grass. The intermediate host animal

consumes the tapeworm eggs, thereby becoming infested, by eating the contaminated pasture contained within this forest or

farmland setting.

An intermediate host animal (usually a livestock animal, such as a sheep or cow, but sometimes a wild animal species, such as a kangaroo or moose) consumes the hydatid tapeworm eggs present in the environment. These

eggs are generally consumed in a pasture or forest-type environmental setting. The infested definitive host animal defecates

onto the pasture (e.g. pasture on a farm) or in the forest (e.g. bushland, national park setting) and, in doing

so, sheds infective tapeworm eggs into this environment. The organic feces break down, but the resistant

tapeworm eggs remain in the environment, speckled invisibly across the grass. The intermediate host animal

consumes the tapeworm eggs, thereby becoming infested, by eating the contaminated pasture contained within this forest or

farmland setting.  The hydatid cyst of Echinococcus granulosus is a large, expanding, fluid-filled structure (see diagram - pale blue outer wall)

with a thin, almost see-through, outer wall (at surgery, it looks a bit like a colourless water-balloon). The inner lining ("germinal lining" - darker blue layer on diagram) of the outer membrane of the hydatid cyst actively buds off small mini-cysts inside of itself.

These inner-cysts, called "brood capsules" (orange on diagram) are miniature replicas of the main hydatid cyst (i.e. tiny 'water balloons' contained within the large, main 'water balloon'). They may float about freely inside of the main cyst or they may remain attached to the inner germinal lining of the main cyst by a thin connective strand. These brood capsules generate within themselves miniature larval tapeworms (termed 'scolices or protoscolices). These tiny larval tapeworm forms (purple on diagram) are the individuals that become the adult tapeworms when the

hydatid cyst is consumed by the definitive host animal (dog). The brood capsules within

the main cyst body sometimes burst, releasing the tiny larval tapeworm protoscolices into

the main cyst structure (pink on diagram) - these sediment out with gravity, settling into the lower regions

of the main cyst as a grainy, tapeworm sediment termed 'hydatid sand'. It is also likely that

the germinal lining of the main hydatid cyst is able to produce and shed hydatid sand without the need

for a burst brood capsule (i.e. the cyst lining can make protoscolices directly while, at the same time, manufacturing brood capsules).

The hydatid cyst of Echinococcus granulosus is a large, expanding, fluid-filled structure (see diagram - pale blue outer wall)

with a thin, almost see-through, outer wall (at surgery, it looks a bit like a colourless water-balloon). The inner lining ("germinal lining" - darker blue layer on diagram) of the outer membrane of the hydatid cyst actively buds off small mini-cysts inside of itself.

These inner-cysts, called "brood capsules" (orange on diagram) are miniature replicas of the main hydatid cyst (i.e. tiny 'water balloons' contained within the large, main 'water balloon'). They may float about freely inside of the main cyst or they may remain attached to the inner germinal lining of the main cyst by a thin connective strand. These brood capsules generate within themselves miniature larval tapeworms (termed 'scolices or protoscolices). These tiny larval tapeworm forms (purple on diagram) are the individuals that become the adult tapeworms when the

hydatid cyst is consumed by the definitive host animal (dog). The brood capsules within

the main cyst body sometimes burst, releasing the tiny larval tapeworm protoscolices into

the main cyst structure (pink on diagram) - these sediment out with gravity, settling into the lower regions

of the main cyst as a grainy, tapeworm sediment termed 'hydatid sand'. It is also likely that

the germinal lining of the main hydatid cyst is able to produce and shed hydatid sand without the need

for a burst brood capsule (i.e. the cyst lining can make protoscolices directly while, at the same time, manufacturing brood capsules).  The hydatid cyst of Echinococcus granulosus is termed a "unilocular cyst" because it

has one main expanding, non-invasive cyst body and keeps its brood capsules internalised

(i.e. the brood capsules and hydatid sand stay within the main cyst body). This is different to the "alveolar hydatid cyst" structure of Echinococcus multilocularis, which generates external

buds of its wall (daughter cysts) on the outside of the main cyst structure, such that they spread aggressively through the intermediate host animal's internal tissues. See notes on E. multilocularis, below.

The hydatid cyst of Echinococcus granulosus is termed a "unilocular cyst" because it

has one main expanding, non-invasive cyst body and keeps its brood capsules internalised

(i.e. the brood capsules and hydatid sand stay within the main cyst body). This is different to the "alveolar hydatid cyst" structure of Echinococcus multilocularis, which generates external

buds of its wall (daughter cysts) on the outside of the main cyst structure, such that they spread aggressively through the intermediate host animal's internal tissues. See notes on E. multilocularis, below.  The definitive hosts - fox (common host), dog, cat, wild canid. The presence of the cat as a major definitive host also makes Echinococcus multilocularis different to E. granulosus. People

must remember to treat their cats for tapeworms in endemic regions.

The definitive hosts - fox (common host), dog, cat, wild canid. The presence of the cat as a major definitive host also makes Echinococcus multilocularis different to E. granulosus. People

must remember to treat their cats for tapeworms in endemic regions.