Veterinary Advice Online: Dog Spaying (Spaying a Female Dog).

Dog

spaying (bitch spaying procedure) - otherwise known as female neutering, dog sterilisation, "fixing", desexing, ovary and uterine ablation, uterus removal or by the medical term:

ovariohysterectomy - is the surgical removal of a female dog's ovaries and uterus for the purposes of canine population control, medical health benefit, genetic-disease control and behavioral modification. Considered to be a basic component of responsible

female dog ownership, the spaying of female dogs is a simple and common surgical procedure that is performed by veterinary clinics all over the world. This page contains everything you, the pet owner, need to know about dog spaying (

female dog desexing). Dog spaying topics are covered in the following order:

1. What is spaying?

2. Canine spaying pros and cons - the reasons for and against spaying a dog.

2a. The benefits of dog spaying (the pros of dog spaying) - reasons for spaying your dog.

2b. The disadvantages of desexing (the cons of dog spaying) - why some people choose not to spay their female dogs.

3. Information about dog spaying age: when to spay a dog.

3a. Current dog desexing age recommendations.

3b. Spaying a puppy - information about the early spay and neuter of young puppies.

4. Canine spaying procedure (dog spay operation) - a step by step pictorial guide to dog spay surgery.

5. Dog Spaying After Care - all you need to know about caring for your female dog after spaying surgery.

Includes information on feeding, bathing, exercising, wound care, pain relief and stopping dogs from licking surgical wounds.

6. Post Spay Complications - Possible surgical and post-surgical (post-op) complications and side effects of spaying a dog.

6a. Pain after dog spaying surgery (e.g. dog walking stiffly, not wanting to sit down and so on).

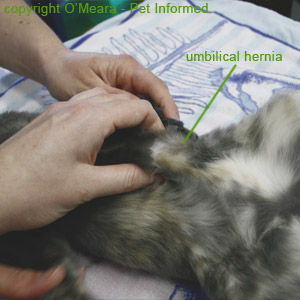

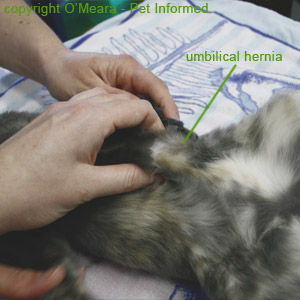

6b. A large 'lump' or 'swelling' at the dog spay operation site (hernias and seromas).

6c. Wound break-down - partial or complete break down of the skin stitches.

6d. Wound infection.

6e. Suture-site reactions - swollen, red skin around sutures or stitches.

6f. Excessive wound hemorrhage (excessive bleeding during or after dog spaying surgery).

6g. Failure to ligate (tie off) the ovarian or uterine (uterus) blood vessels adequately.

6h. Peritonitis.

6i. Ureter laceration.

6j. Post-operative renal failure (kidney failure).

6k. Anaesthetic death.

7. Late complications or problems associated with spaying female dogs.

7a. Weight gain after dog spaying.

7b. Ovarian remnants (incomplete dog spay) - the spayed dog goes into heat after dog spaying surgery.

7c. Incontinence after dog spaying.

8. Frequently asked questions (FAQs) and myths about spaying female dogs:

8a. Myth 1 - All desexed bitches gain weight (get fat).

8b. Myth 2 - Without her reproductive organs, a female dog (bitch) won't "feel like a woman".

8c. Myth 3 - Female dogs need to have sex before being desexed.

8d. Myth 4 - Female dogs should be allowed to give birth to a litter before being spayed.

8e. Myth 5 - Vets just advise neutering for the money not for my dog's health.

8f. FAQ 1 - Why won't my veterinarian clean my dog's teeth at the same time as spaying her?

8g. FAQ 2 - Why shouldn't my vet vaccinate my dog whilst she is under anaesthetic?

8h. FAQ 3 - Can my dog be spayed whilst she is in heat?

8i. FAQ 4 - Spaying a pregnant dog - can my pregnant dog be spayed?

8j. FAQ 5 - My pregnant dog needed a caesarean (C-section) - can she be spayed at the same time?

8k. FAQ 6 - Incontinence after dog spaying - will spaying make my dog incontinent?

8l. FAQ 7 - Is dog spaying safe? It's just a routine procedure isn't it?

8m. FAQ 8 - My veterinarian offered to perform a pre-anaesthetic blood screening test - is this necessary?

8n. FAQ 9 - When is canine spaying surgery high-risk or not safe to perform?

9. The cost (price) of spaying female dogs:

9a. The typical cost of spaying a female dog at a veterinary clinic.

9b. Where and how to source discount and low cost spaying.

9c. Free canine spaying.

10. Alternatives to spaying your dog:

10a. Dog birth control method 1 - separate the male dog from the female and prevent her from roaming.

10b. Dog birth control method 2 - neuter your male dog and keep your female dog inside.

10c. Dog birth control method 3 - "the contraceptive pill" and hormonal female oestrus (heat) suppression.

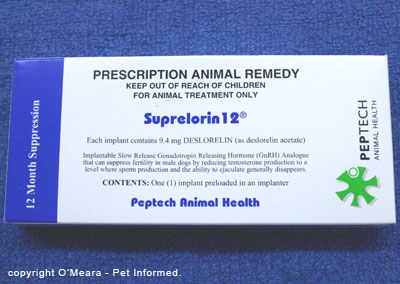

10d. Dog birth control method 4 - "male pill" - fertility suppressing implants (contraceptives) for male dogs.

10e. Canine birth control method 5 - male canine vasectomy.

WARNING - IN THE INTERESTS OF PROVIDING YOU WITH COMPLETE AND DETAILED INFORMATION, THIS SITE DOES CONTAIN MEDICAL AND SURGICAL IMAGES THAT MAY DISTURB SENSITIVE READERS.

1. What is spaying?

1. What is spaying?

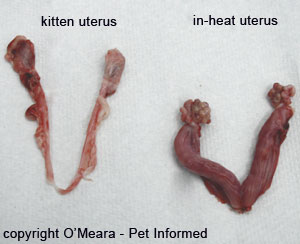

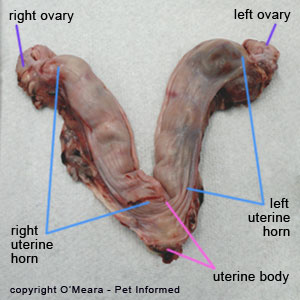

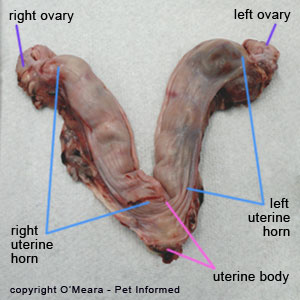

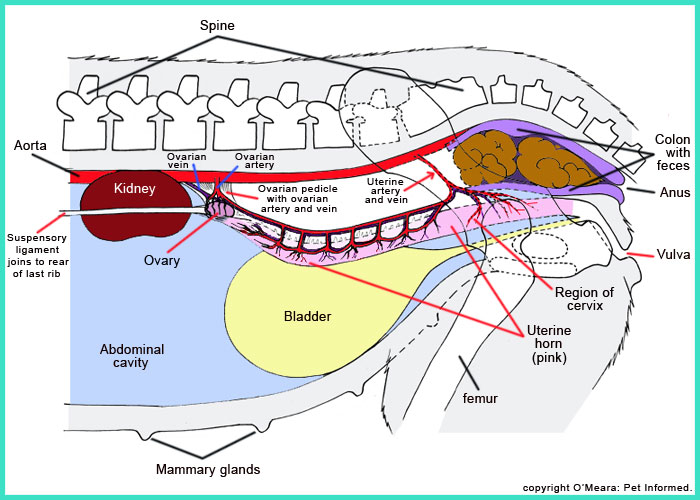

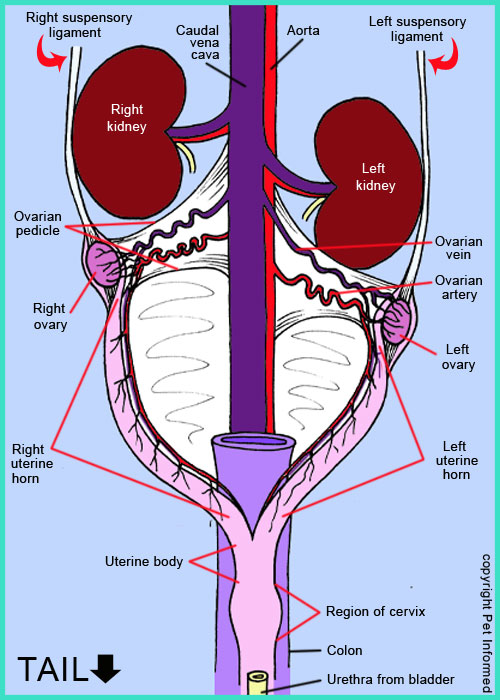

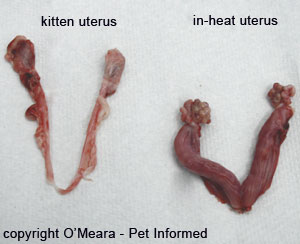

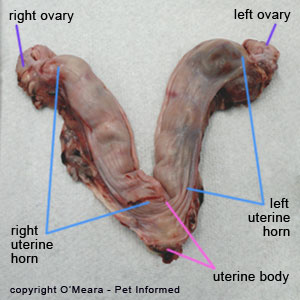

Dog spaying or desexing is the surgical removal of a female (bitch) dog's internal reproductive structures including her ovaries (the site of ova/egg production), Fallopian tubes, uterine horns (the two long tubes of uterus where the fetal puppies develop and grow) and a section of her uterine body (the part of the uterus where the uterine horns merge and become one body). The picture on the right shows a dog uterus that has been removed by dog spaying surgery - it is labeled to give you a clear illustration of the reproductive structures that are removed during surgery.

Dog spaying or desexing is the surgical removal of a female (bitch) dog's internal reproductive structures including her ovaries (the site of ova/egg production), Fallopian tubes, uterine horns (the two long tubes of uterus where the fetal puppies develop and grow) and a section of her uterine body (the part of the uterus where the uterine horns merge and become one body). The picture on the right shows a dog uterus that has been removed by dog spaying surgery - it is labeled to give you a clear illustration of the reproductive structures that are removed during surgery.

Basically, the parts of the female reproductive tract that get removed are those which are responsible for egg (ova) production, embryo and fetus development and the secretion of the major female reproductive hormones (oestrogen and progesterone being the main female reproductive hormones). Removal of these structures plays a huge role in canine population control (without eggs, the female dog can not produce young; without a uterus, there is nowhere for the unborn puppies to develop); canine genetic disease control (female dogs with genetic disorders can not pass on their inheritable disease conditions to any young if they can not breed); the prevention and/or treatment of various medical disorders (spaying prevents and/or treats a number of ovarian and uterine diseases as well as various hormone-enhanced medical conditions)

and female dog behavioral modification (e.g. estrogen is responsible for many female dog behavioral traits that some owners find problematic - e.g. roaming, blood spotting during proestrus, attractiveness and attraction to male dogs - and dog spaying, by removing the ovarian source of female hormones, may help to resolve these issues).

2. Canine spaying pros and cons - reasons for and against spaying a dog.

2a. Benefits of spaying (pros of spaying) - reasons for spaying your dog.

There are many reasons why veterinarians and pet advocacy groups recommend the desexing of

entire female dogs. Many of these reasons are listed below, however the list is by

no means exhaustive.

1. The prevention of unwanted litters:

Pet overpopulation and the dumping of unwanted litters of puppies (and kittens) is an

all-too-common side effect of irresponsible pet ownership. Every year, thousands of unwanted puppies and older dogs are surrendered to shelters and pounds for rehoming or dumped on the street (street-dumped animals ultimately end up dying from starvation, predation or transmissible

canine diseases or finding their way into pounds and shelters that may or may not be

able to find homes for them). Many of these animals do not ever get adopted from the pounds and shelters that take them in and those that don't get adopted often end up being euthanased. This sad waste of healthy life can be reduced by not letting pet dogs breed indiscriminately and the best way of preventing any accidental, unwanted breeding from occurring is through the routine neutering of all non-stud (non-breeder) female dogs (and male dogs too, but this is another page).

Pet overpopulation and the dumping of unwanted litters of puppies (and kittens) is an

all-too-common side effect of irresponsible pet ownership. Every year, thousands of unwanted puppies and older dogs are surrendered to shelters and pounds for rehoming or dumped on the street (street-dumped animals ultimately end up dying from starvation, predation or transmissible

canine diseases or finding their way into pounds and shelters that may or may not be

able to find homes for them). Many of these animals do not ever get adopted from the pounds and shelters that take them in and those that don't get adopted often end up being euthanased. This sad waste of healthy life can be reduced by not letting pet dogs breed indiscriminately and the best way of preventing any accidental, unwanted breeding from occurring is through the routine neutering of all non-stud (non-breeder) female dogs (and male dogs too, but this is another page).

Author's note: The deliberate breeding of family dogs should never be considered an

easy way to make a quick buck. A lot of cost and effort and expertise goes into producing a quality litter of puppies for profitable sale. And that's only if nothing goes wrong! If your bitch

needs a caesarean section at one in the morning or develops a severe infection after whelping (e.g. metritis, mastitis), then all of your much planned profits will rapidly turn into financial losses (the vet fees for these kinds of treatments are high). On top of that, if you fail to do your homework and you breed poor quality puppies or poorly socialized

pups that won't sell, then you've just condemned some of those young animals to a miserable

life of being dumped in shelters or on the streets.

2. The reduction of stray and feral dog populations:

By having companion dogs spayed at young ages, they are unable to become pregnant. This results in fewer litters of unwanted puppies being born

which, in return, benefits not just those unwanted pups (dumped or shelter-surrendered

pups can often lead a tough, neglected life), but also society and the environment in general. A proportion of the unwanted puppies that are dumped into the environment (e.g. the Australian bush) do survive and grow up to become feral dogs, which in turn reproduce to produce more feral dogs. Feral and stray dog populations pose a significant risk of predation to native wildlife; they account for many thousands

of dollars in stock and farming losses (livestock killing - see image opposite); they carry diseases that may affect humans (e.g. rabies, worms, dog-bites) and their pets (e.g. rabies, parasites, parvo virus, distemper); they fight with domestic pets, inflicting nasty dog-fight wounds and abscesses; they kill smaller domestic

pets (e.g. pet cats, small dogs, rabbits and livestock); they steal the food of domestic pets and they place a huge financial and emotional burden on the

pounds, shelters and animal rescue groups which have to deal with them.

By having companion dogs spayed at young ages, they are unable to become pregnant. This results in fewer litters of unwanted puppies being born

which, in return, benefits not just those unwanted pups (dumped or shelter-surrendered

pups can often lead a tough, neglected life), but also society and the environment in general. A proportion of the unwanted puppies that are dumped into the environment (e.g. the Australian bush) do survive and grow up to become feral dogs, which in turn reproduce to produce more feral dogs. Feral and stray dog populations pose a significant risk of predation to native wildlife; they account for many thousands

of dollars in stock and farming losses (livestock killing - see image opposite); they carry diseases that may affect humans (e.g. rabies, worms, dog-bites) and their pets (e.g. rabies, parasites, parvo virus, distemper); they fight with domestic pets, inflicting nasty dog-fight wounds and abscesses; they kill smaller domestic

pets (e.g. pet cats, small dogs, rabbits and livestock); they steal the food of domestic pets and they place a huge financial and emotional burden on the

pounds, shelters and animal rescue groups which have to deal with them.

3. To reduce the spread of inferior genetic traits, genetic diseases and congenital deformities:

Dog breeding is not merely the production of puppies, it is the transferral of genes and genetic traits from one generation to the next in a breed population. Pet

owners and breeders should desex female dogs that have conformational, coloring and temperamental traits,

which are unfavorable or faulty to the breed as a whole, to reduce the spread of these

defects further down the generations. Female dogs with heritable genetic diseases and

congenital defects/deformities should also be desexed to reduce the spread of these

genetic diseases to their offspring.

Some examples of proven-heritable or suspect-heritable diseases that we select against

when choosing to spay dogs include: hip and elbow dysplasia, polycystic kidney disease (PKD), cryptorchidism, collie eye anomaly, lysosomal storage diseases, amyloidosis and dilated cardiomyopathy. There are many others.

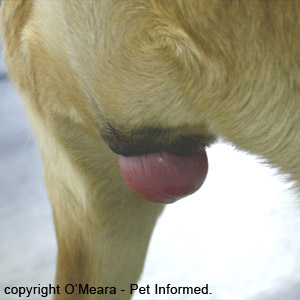

Picture: This is a close up image of the vulva of a bitch (?) with hermaphrodism (canine hermaphrodite). Her clitoris is massively enlarged, forming a miniature penis that protrudes from the vulva.

Animals with hermaphrodism are of poor breeding quality (they are often, but not always, infertile)

and many may even have significant sex-chromosome defects (e.g. XX/XY chimeras). These animals should be desexed and not bred from.

Dog uterus images: These photos show a female dog uterus that has one normal uterine horn (the horn on the left side) and one non-existent, undeveloped uterine horn (the uterus horn on the right side). This dog was born

with this defect (it was found by accident during dog spaying surgery). Because the undeveloped right uterine horn can not produce any puppies, this defect would naturally

result in a greatly reduced fecundity (fecundity refers to the number of pups born per litter) for this particular bitch, were she to be used as a breeding dog. Any female with such a significant reproductive tract

birth defect should never be chosen as a breeding animal because, should the defective uterine condition be found to be heritable, then the generations succeeding her could be afflicted with a similar genetic tendency towards poor litter sizes (never a desirable trait in a breeding population).

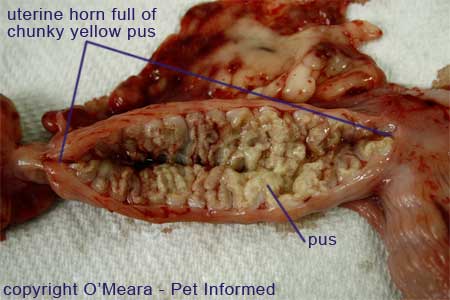

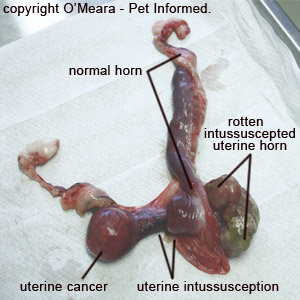

4. The prevention and/or treatment of ovarian and uterine diseases:

It is difficult to contract an ovarian or uterine disease if you have no ovaries or uterus. Early dog spaying prevents female dogs from contracting a range of ovarian and uterine diseases and disorders including: uterine cancer, ovarian cancer, polycystic ovaries, metritis or endometritis (severe uterine or uterine wall inflammation, often with bacterial infection, usually seen after whelping), mucometra (a uterus full of glandular mucus), cystic endometrial hyperplasia (large cysts in the wall of the uterus

that predispose dogs to pyometra), pyometra or pyometron (infection and abscessation of the uterus that is similar to metritis and endometritis, but not usually associated with pregnancy and whelping), ectopic pregnancy (pregnancy outside of the uterus), uterine prolapse and uterine torsion.

Image 1: This is an ultrasound image of a large ovarian cancer (4-5cm in diameter) that was taken from a 5kg dog. The black spaces/holes that you can see throughout the mass are mutated 'ovarian follicles' (fluid-filled cystic

structures akin to those "true ovarian follicles" which produce the ova/eggs in a normally-functioning ovary) that the cancerous ovarian follicular cells have produced in an attempt to mimic their normal function within the ovary.

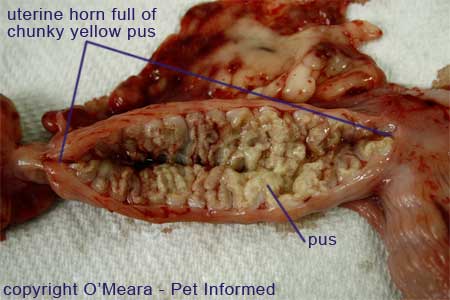

Image 2: This is a photographic image of a post-mortem performed on a dog who died from pyometra (infection of the uterus). The dog's uterus (which looks like an enormous number "3" laying on its side) was massively enlarged and completely full of infection and pus - a classic case of canine pyometra. The dog died because

bacteria from the infected uterus invaded the dog's blood stream, causing septicaemia and blood poisoning.

The condition could have been prevented by desexing surgery.

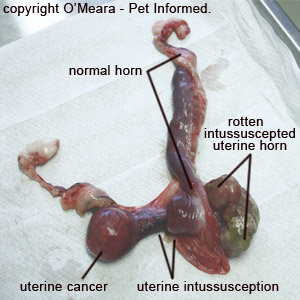

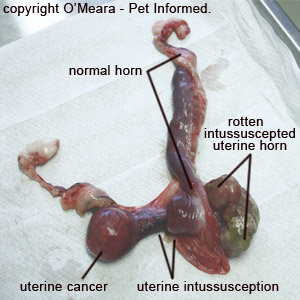

Image 3: This is a rabbit uterus with two major problems, both of which could have been prevented

by early rabbit spaying surgery. The uterus contains a large (2cm diam) uterine cancer. It also contains

a uterine intussusception. A uterine intussusception is a condition whereby one section of a uterine horn telescopes into another section of the uterine horn. The telescoped uterine horn becomes strangled inside the other section of uterine horn (as seen in this image), causing it to die and rot and become necrotic (decaying tissue). You can see the dead telescoped section of uterus in this image - it is green in color and gangrenous.

5. The prevention or reduction of hormone-induced diseases:

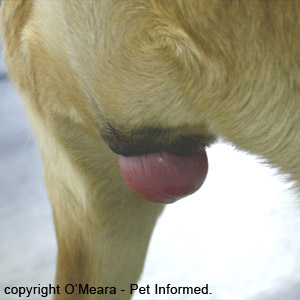

It is well known that entire female dogs do suffer from a range of diseases and medical conditions that are directly associated with high blood estrogen and/or progesterone levels (the hormones produced by the ovaries). These conditions include: vaginal hyperplasia (a large swelling of the roof of the vaginal passage, which results in a large red or pink ball of flesh protruding from the bitch's vulva - see image below); mammary neoplasia (breast cancer in dogs is greatly influenced by hormones and bitches spayed prior to their first season

almost never develop the condition); mammary enlargement; cystic endometrial hyperplasia; pyometron

(the development of uterine conditions favorable to the development of uterine infection or pyometra is greatly reliant on

seasonal ovarian reproductive hormone fluctuations); pseudopregnancy (false pregnancy or phantom pregnancy with accompanied signs of 'expecting' including: nesting behaviours, abdominal enlargement, breast enlargement and even lactation) and certain desexing-responsive skin disorders (e.g. estrogen-induced dermatoses).

Some entire bitches develop follicular cysts on their ovaries (also termed polycystic ovaries - ovaries with too many actively-secreting ovarian follicles), which produce excessive amounts of oestrogen, well above the quantities usually

seen in a normal entire bitch. Excessive estrogen is termed hyperestrogenism and it can result in a number of estrogen-induced behavioral problems

manifesting (e.g. nymphomania, excessive libido, mounting toys) as well as a range of potentially

life-threatening medical problems including: bone marrow suppression (oestrogen toxicity shuts down the bone marrow, causing complete failure of production of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets), blackening of the skin (hyperpigmentation), hairloss and/or poor coat quality and abnormally increased mammary development.

High levels of ovary-derived reproductive hormones (e.g. progesterone) can also interfere with the management of

other medical conditions. Diabetes mellitus is a good example of this. Progesterone inhibits the action of insulin on

the body cells' insulin receptors, producing a condition called 'insulin resistance' or Type 2 diabetes (similar to parturient diabetes or 'pregnancy diabetes' seen in women). What essentially happens is that any insulin (e.g. Caninsulin, Actrapid and others) given to the pet to manage its diabetes does not work as effectively in the presence of progesterone. This can make the animal's diabetes very difficult to control every time it has a season and it is one of the main reasons why vets recommend the desexing of diabetic dogs as part of the management of the disease. Other diseases whose severity or management can also be adversely affected by high reproductive hormone levels include acromegaly, epilepsy, Cushing's disease (Hyperadrenocorticism) and generalised Demodex mites.

Desexing removes the main source of oestrogen and progesterone from the animal's body (the ovaries), which not only prevents the onset of these diseases or conditions, but can even help to control or manage these diseases if they are already present.

Photograph: This is an image of the vulva of a bitch with vaginal hyperplasia, also called vaginal prolapse

(some people, incorrectly, term this condition uterine prolapse, however, uterine prolapse is

a different condition altogether). The red or pink swelling protruding from the vulval opening is

the roof of the dog's vagina. This condition is hormonal and can usually be resolved through dog spaying surgery.

Picture: Whilst not exactly a disease per se, many owners elect to get their female dogs spayed

so that they will cease displaying all of the annoying signs of pro-estrus and oestrus (heat), in particular vulval enlargement and

blood spotting (dog "period") in the house. The image above shows the vulva of a dog in pro-estrus

(early season). The vulva is swollen and a blood-tinged discharge is coming from the vulval opening.

6. The prevention or reduction of hormone-mediated behavioural problems:

The ovaries are responsible for producing estrogen and progesterone: the hormones that make female animals look and act like female animals. It is the ovaries that make female dogs

exhibit the kinds of "female" hormone-dependent behaviors normally attributed to the entire animal. Entire female dogs are more likely to exhibit sexualised behaviors including: aroused interest in males of their own species; nymphomania

(excessive sexual and mating drive) and excessive affection and sexual interest towards their owners (in-heat dogs

can often drive their owners nuts by constantly putting their bottoms in their owners' faces,

rubbing up against them and mounting toys and legs). Pre-heat dogs just coming

into season can sometimes be moody and unpredictable (PMS?) and they may threaten or bite

owners and other household pets who get too close to them or touch them on the rump. Some of the more dominant cycling females will even display unwanted dominance and territorial behaviors such the marking of territory with urine (although much more commonly exhibited by entire male dogs, some dominant females will also exhibit urine marking in the house) and the guarding of food, nesting sites and other resources. Additionally, entire, in-heat female dogs are much more likely than neutered animals are

to leave their yards and roam the countryside looking for males and trouble. Roaming is a troublesome habit because it puts other animals (wildlife and other pets) and humans at risk of harm from your canine pet and it puts the roaming pet at risk from all manner of dangers including: predation by other animals, attacks by other dogs, cruelty by humans, poisoning, envenomation (e.g. snake bite) and motor vehicle strikes. The spaying of entire female dogs may help to reduce some of these problematic hormone-mediated behaviours.

Author's note: Fighting between dogs, even dogs living within the same house-hold, is more common when dogs are left entire

and undesexed. Although fighting is much more common between entire male dogs, fighting can

also occur between male and female dogs when a male attempts to mate with a female who

is not yet receptive to his advances. Such advances can result in the female dog attacking the male and

receiving wounds in return. Fighting can also occur between entire bitches in the same household when one of the bitches (particularly a subordinate female) comes into heat. The onset of estrus

(heat or season) affects the in-season-subordinate's smell and, consequently, her perceived standing within the bitch hierarchy (in wild dog society, only the alpha or top female is permitted to cycle and breed), which, if

taken as a threat by the dominant females in the house-hold, can result in very aggressive fighting

and severe injury. Owners of fighting dogs often spend hundreds to thousands of dollars treating their

pets for fight wounds and dog-fight abscesses. By reducing their attractiveness to male dogs and also their perceived threat/challenge towards other intact female dogs, dog spaying reduces the incidence

of fighting and its secondary complications (clawed and lacerated eyes, dog-fight abscesses and so on).

Important author's note: Whilst desexing or neutering is usually valuable in reducing many forms

of aggression in entire male dogs, some forms of aggression in female dogs can actually

become worse after desexing surgery. This is thought to occur because of the loss of progesterone

that occurs as a result of ovary removal. Progesterone hormone has a calming, mood-quietening effect

on many female animals and the loss of it can result in mood-alteration and an increased tendency towards certain forms of aggression. If your bitch is already aggressive and you are considering having her

desexed, I recommend that you consult with your vet or an animal behaviouralist before dog spaying surgery

is performed in order to determine whether this surgery is appropriate for her at this current time.

7. The reduction of male dog attraction:

When a female dog comes into heat, she releases pheromones and hormones in her urine that

notify male dogs of her increased fertility. These hormones and pheromones can be detected by

male dogs from many miles away. It is, therefore, not uncommon

for the owners of undesexed, in-heat female dogs to have male dogs constantly coming into their yards

at all times of the day and night.

This is a problem for many reasons. Firstly, the wandering dogs will

fight amongst themselves, producing a lot of ruckus and injury in the middle of the night. Secondly, the trespassing dogs will fight with the house owner's dogs, resulting in injuries and costly dog fight

abscesses and, potentially, the spread of diseases like rabies. The roaming dogs may also predate upon the

house-owner's other pets, including any small domesticated pets (cats, rabbits, poultry etc.)

and livestock. Thirdly, the roaming dogs will void urine and feces in the female-dog owner's yard, which kills the plants and grass and leaves behind a pungent and noxious odor. Sometimes, the male dogs will even venture into the female-dog owner's house (they certainly will if there is a pet flap), where they will steal food and mate with the in-heat female in question. If the female dog does escape the house, she is almost certain to be mated and to fall pregnant. If the female dog is living outside in a backyard,

even a seemingly-well-fenced yard, then she is also highly likely to become pregnant (male dogs will

climb and scale great heights and dig under fences and push through heavy gates to access and mate with

a female dog on heat).

By spaying all of the female dogs in your household, there will be nothing to attract

the male dogs into your yard and, consequently, the problem of trespassing stray dogs will

be solved.

2b. The disadvantages of desexing dogs (the cons of spaying dogs) - why some people choose not to spay their female dogs.

There are many reasons why some individuals, breeders and pet groups choose not to advocate

the sterilization of entire female dogs. Many of these reasons have been listed below, however the list is by

no means exhaustive.

1. The dog may become overweight or obese:

Studies have shown that spayed and neutered animals probably require around 25% fewer calories

to maintain a healthy bodyweight than entire female animals of the same size do. This is because a neutered animal

has a lower metabolic rate than an entire animal does (it therefore needs fewer calories to maintain its bodyweight). Because of this, what tends to happen is that most owners, unaware of this fact, continue to feed their spayed dogs the same amount of food calories after the surgery that they did prior to the surgery, with the result

that their canine pets become fat. Consequently, the myth of automatic post-desexing obesity has become perpetuated

and, as a result, many owners simply will not consider desexing their female dogs because

of the fear of them gaining weight and developing weight-related problems.

Author's note: The fact of the matter is that dogs will not become obese simply because they have been desexed. They will only become obese if the post-dog-spaying drop in their metabolic rate

is not taken into account and they are fed the same amount of food calories as an entire animal.

Author's note: Those of you who care about your finances might even be able to see the benefits of desexing here. A spayed dog potentially costs less to feed than an entire animal

of the same weight does and, therefore, neutering your animal may well save you money

in the long run.

2. Desexing equates to a loss of breeding potential and valuable genetics:

There is no denying this. If a dog or cat or horse or other animal is the 'last of its line' (i.e. the last puppy in a long line of pedigree breeding dogs), a breeder or pet owner's choice to desex that animal and, therefore, not pass on its valuable breed genetics will essentially spell the end for that breeding lineage.

Author's opinion point: of all the reasons given here that argue against the desexing of female dogs, this is probably the only one that has any real merit. Desexing does equate to a loss of breeding potential. In an era where many unscrupulous breeders

and pet owners ("backyard breeders" we call them) will breed any low-quality dog, regardless of

breed traits and temperament, to make a quick buck, the good genes for breed soundness, breed

traits and good temperament are needed more than ever. Desexing a purebred female dog with good breed

characteristics, good temperament and no genetically heritable defects/diseases will

count as a loss for that breed's quality in general, particularly if there are a lot of subquality

females around saturating the breeding circles.

3. Loss of estrogen or underexposure to estrogen as a result of desexing (especially early age dog spaying) may result in the underdevelopment of feminine characteristics,

the retention of immature juvenile behaviours and cause urinary incontinence:

The ovaries are responsible for producing progesterone and estrogen: the hormones that make mature female animals look and act like female animals. It is the hormones produced by the ovaries that cause female animals to develop the distinctive body characteristics normally attributed to the entire female animal. These include: increased vulval size and development;

mature breast (mammary) development and enlargement; increased maturity and emotional development; increased sex drive and libido and, controversially, improved bladder control and continence.

Desexing, particularly early age desexing (prior to the first season), may limit the development of mature feminine features such that they remain immature and juvenile-looking throughout life (i.e. the mammaries remain tiny and the vulva remains tiny). In overweight individuals

(see image opposite) underdevelopment of the vulva as a result of early-age desexing (termed vulval hypoplasia), can result in the tiny vulva being 'swallowed up' within the roll of fat that borders

the vulval region. Encased within this fat roll, the vulva and perivulval skin (skin surrounding the vulva)

will tend to become scalded with urine and prone to retaining moisture, both of which will tend to result in vulval dermatitis, vaginal yeast infections, vulval itchiness and, potentially, an

increased risk of ascending urinary tract infections.

Desexing, particularly early age desexing (prior to the first season), may limit the development of mature feminine features such that they remain immature and juvenile-looking throughout life (i.e. the mammaries remain tiny and the vulva remains tiny). In overweight individuals

(see image opposite) underdevelopment of the vulva as a result of early-age desexing (termed vulval hypoplasia), can result in the tiny vulva being 'swallowed up' within the roll of fat that borders

the vulval region. Encased within this fat roll, the vulva and perivulval skin (skin surrounding the vulva)

will tend to become scalded with urine and prone to retaining moisture, both of which will tend to result in vulval dermatitis, vaginal yeast infections, vulval itchiness and, potentially, an

increased risk of ascending urinary tract infections.

Early desexing may also cause the spayed pet to remain emotionally and mentally immature well into adulthood (i.e. the animal

retains many of its juvenile, puppyish behavioural characteristics). Not that this is always a problem. Emotionally immature dogs retain a lot of the playfulness and curiosity of their puppy-hood:

cute traits that most dog-loving owners are all too keen to keep hold of. The only time that

this inappropriate immaturity can become an issue is when the pet in question is meeting other adult dogs. A fully grown dog with overly-playful puppy qualities pouncing up to another adult dog is likely to be misread by that other dog and bitten.

The incontinence issue is still a matter of debate (see FAQ 6, section 8, for more info). It has

long been said that estrogen plays a significant role in the development and maturation

of bladder sphincter tone (basically, how 'tight' and resistant to urine leakage the bladder neck is)

and that early age spaying can result in a weakness of this bladder tone, such that

the animal is prone to incontinence and urine leakage (i.e. dribbling urine involuntarily, particularly during sleep). Certainly, the once-common use of oestrogen products (e.g Stilbestrol)

in the management of female dog incontinence problems does support this idea as does the fact

that most of our incontinent pets (esp. dogs) are desexed females. As will be discussed in FAQ 6, however, although there is much merit to the desexing-causing-incontinence idea (particularly in the case of dogs and early-age spaying), there is still some controversy about whether it is the loss of oestrogen per se that produces the problem

or whether it is the spay technique itself (i.e. changing spay techniques may alleviate the risk).

Either way, regardless of the underlying causative mechanism, when it does occur, post-desexing incontinence and urine soiling can be a major problem for the animal and its owner.

This is particularly so if the animal lives indoors (wetting on the bed or carpet is unhygienic and poorly tolerated) or in a place with high blowfly populations (urine soiled

bottoms are prone to flystrike). The risk of the condition happening is certainly a significant reason why many owners (in particular, dog owners) might decide against having their female animals desexed.

4. As an elective procedure, dog spaying is risky:

Certainly, female dog desexing is a more risky and invasive procedure to perform than male dog desexing is. Having said that, the incidence of major complications associated with routine (i.e. non-pregnant, non-diseased uterus) dog spaying procedures is still very low and, therefore, no reason to avoid having a dog spayed. See sections 6 and 7 for more on spay complications.

5. As an elective procedure, dog spaying costs too much:

The high cost of veterinary services, including desexing, is another big reason why some

pet owners choose not to get their pets desexed. See section 9 for more on the costs of dog spaying.

Author's note: Having said this, the costs of canine caesarian section or having a pregnant dog desexed are significantly higher than the costs of a routine dog spay.

6. The dog will "no longer be a woman" without her ovaries and uterus:

It sounds silly, but it is a very common reason why many owners refuse to get their female dogs spayed. See myth 2 (section 8b) for more.

3. Information about dog spaying age: when to spay a dog.

The following two subsections discuss desexing age recommendations and how they have been established as well as the pros and cons of early age (8-16 weeks) dog spaying (spaying a puppy).

3a. Current dog spaying age recommendations.

In Australia and throughout much of the world, it has always been recommended that female dogs be

spayed at around 5-7 months of age and older. As far as the "older" goes, the closer to the

5-7 months of age mark the better - there is less chance of a female dog becoming pregnant or developing a ovarian or uterine disorder or a hormone-mediated medical condition if she is desexed at a younger age.

In addition to this, it has always been advised that it is best if a female dog is desexed prior to

the onset of her first season as this will greatly reduce the risks of the animal developing

mammary cancer (breast cancer) in the future.

The reasoning behind this 5-7 month age specification is mostly one of anaesthetic safety for elective procedures.

When asked by owners why it is that a dog needs to wait until 5-7 months of age to be spayed, most veterinarians will simply say that it is much safer for them to wait until this age before undergoing a general anaesthetic procedure. The theory

is that the liver and kidneys of very young animals are much less mature than those of older animals and therefore less capable of tolerating the effects of anaesthetic drugs and less effective at metabolizing them and breaking them

down and excreting them from the body. Younger animals are therefore expected to have

prolonged recovery times and an increased risk of suffering from severe side effects, in particular liver and kidney damage, as a result of general anaesthesia. Consequently, in order to avoid such problems, many vets will choose not to anesthetize a young puppy until at least 5 months of age for any elective procedure, including dog spaying.

The debate:

Whether this 5-7 month age specification for general anaesthesia and desexing is valid nowadays (2008 onwards), however,

is much less clear and is currently the subject of debate. The reason for the current

desexing-age debate is that the 5-7 month age specification was determined ages ago, way back in the days when animal anaesthesia was nowhere near as safe as it is now and relied heavily upon drugs that were more cardiovascularly depressant than modern drugs (e.g. put more strain on the kidneys and liver) and required a fully-functioning, almost-adult liver and kidney to metabolize and excrete them from the body. Because modern animal anaesthetic drugs are so much safer on young animals than the old drugs used to be, there is increasing push to drop the age of desexing in veterinary practices. This puts us onto the topic of early age dog spaying (see next section - 3b).

Are there any disadvantages to desexing at the normal time of 5-7 months of age?

Just as there are disadvantages associated with desexing an animal at a very young age (see section 3b), there

are also some disadvantages associated with spaying at the usually-stated age of 5-7 months:

- Some people find it inconvenient to wait until 5-7 months of age to desex.

- There is the chance that an early-maturing female dog may be able to mate and produce unwanted puppies before this age. This is not only bad for the underage mother dog (a mother dog

allowed to have pups at under 5-7 months is not physically or emotionally mature enough to have

puppies - she is still a baby herself), but it potentially adds to the number of unwanted litters being destroyed and/or dumped.

- For people who choose to have their pets microchipped during anaesthesia, there is an inconvenient

wait of 5-7 months before this can be done. If the animal gets lost prior to this age, the unchipped dog may fail to find its way home.

- Some of the behavioural issues commonly associated with entire female animals may

become manifest before the time of the desexing age recommendations (e.g. urine marking, dog aggression, roaming). These behavioural problems, once established, may persist and remain problematic even after the animal is sterilized.

3b. Spaying a puppy - information about the early spay and neuter of young puppies.

As modern pet anesthetics have become a lot safer, with fewer side effects, the

debate about the recommended age of canine spaying has been reopened in the veterinary world

with some vets now allowing their clients to opt for an early-age spay or neuter, provided they

appreciate that there are greater, albeit minimal, anaesthetic risks to the very young pet when compared to the

more mature pet. In these situations, dog owners can now opt to have their male and female

pets desexed as young as 8-9 weeks of age (the vet chooses anaesthetic drugs that are not as cardiovascularly depressant and which do not rely as heavily upon extensive liver and kidney metabolism and excretion).

As modern pet anesthetics have become a lot safer, with fewer side effects, the

debate about the recommended age of canine spaying has been reopened in the veterinary world

with some vets now allowing their clients to opt for an early-age spay or neuter, provided they

appreciate that there are greater, albeit minimal, anaesthetic risks to the very young pet when compared to the

more mature pet. In these situations, dog owners can now opt to have their male and female

pets desexed as young as 8-9 weeks of age (the vet chooses anaesthetic drugs that are not as cardiovascularly depressant and which do not rely as heavily upon extensive liver and kidney metabolism and excretion).

Powerful supporters of the early spay and neuter - in 1993, the AVMA (American Veterinary Medical Association) advised that

it supported the early spay and neuter of young cats and dogs, recommending that puppies

and kittens be spayed or neutered as early as 8-16 weeks of age.

IMPORTANT - because of the rising problems of pet and feral animal overpopulation,

it is now the law in many states (e.g. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory) for cats

to be desexed prior to 12 weeks of age. In the case of Canberra dogs, the law (as of 2009) specifies that

all male and female dogs now be desexed unless their owner is in possession of a breeder's licence. No canine desexing age has yet been specified, so dog owners can still opt to desex their pets earlier (from 8 weeks) or at puberty (5-7 months), depending on their own personal preferences. This dog spaying law may soon change, however, in line with cat spaying laws, making it compulsory for dog owners to have their pets desexed before a certain age. In some countries, states and territories, age specifications may already be in place for the spaying of dogs.

Owners of dogs (and cats) need to check their local state laws on pet neutering ages - it may be compulsory

in your area for your pet to undergo early age desexing regardless of any minor increases in anaesthetic risk

that might be incurred.

The advantages of the early spay and neuter of young dogs:

Certainly, there are some obvious advantages to choosing to desex an animal earlier rather

than later. These include the following:

- People do not have to wait 5-7 months to spay their pets. The procedure can be over and done with earlier.

- Dogs spayed very early will not attain sexual maturity and will therefore be unable to fall pregnant and give

birth to any puppies. This role in canine population control is why most shelters choose to neuter early.

- Dogs spayed very early will not attain sexual maturity and will therefore be unable to fall pregnant. Consequently, owners of female dogs will not have to deal with the dilemma of having an 'accidentally' pregnant pet and all of the ethical issues this problem poses (e.g. What do I do with the pups? It is right to desex a pregnant animal before the puppies are born? Is it right to give a dog an abortion? ... and so on). Likewise, veterinary staff also benefit from not having to perform dog desexing surgery on pregnant animals, a procedure that many staff find very confronting.

- It makes it possible for young puppies (6-12 weeks old) to be sold by breeders and pet-shops already desexed. This again helps to reduce the incidence of irresponsible breeding - dogs sold already desexed cannot reproduce.

- For owners who choose to get their pets microchipped during anaesthesia, there is no inconvenient wait of 5-7 months before this can be done.

- Some of the behavioural problems and concerns commonly associated with entire female animals may be prevented altogether if the puppy is desexed well before achieving sexual maturity (e.g. marking territory, roaming, estrus blood spotting, in-heat aggression).

- Some of the medical problems and concerns commonly associated with entire female animals may be prevented altogether if the puppy is desexed well before achieving sexual maturity. In particular, breast cancer (mammary cancer)

in dogs is almost non-existent in animals that are desexed prior to their first season.

- From a veterinary anaesthesia and surgery perspective, the duration of dog spaying surgery and anaesthesia is much shorter for a smaller, younger animal than it is for a fully grown, mature animal. I take about 5-10 minutes to neuter a female puppy of about 9 weeks of age compared to about 15-25 minutes for an older female and even longer if she is large-breed, obese, in-heat or pregnant.

- The post-anaesthetic recovery time is quicker and there is less bleeding associated with an early spay or neuter procedure.

- From a veterinary business perspective, the shorter duration of surgery and anaesthesia time is good for business. More early age dog spays can be performed in a day than mature dog spays and less anaesthetic is used on each individual, thereby saving the practice money per procedure.

- Routine, across-the-board, early spay and neuter by shelters avoids the need for a sterilization contract to be signed between the shelter and the prospective dog owner. A sterilization

contract is a legal document signed by people who adopt young, non-desexed puppies and kittens, which declares that they will return to the shelter to have that dog or cat desexed when it has reached the recommended sterilization age of 5-7 months. The problem with these sterilisation contracts is that, very often, people do not obey them (particularly

if the animal seems to be "purebred"); they are rarely enforced by law and, consequently, the adopted animal is often left undesexed and able to breed and the cycle of pet reproduction and dumped litters continues.

The disadvantages associated with the early spay and neuter of young puppies:

There are also several disadvantages associated with choosing to desex an animal earlier rather

than later. Many of these disadvantages were outlined in the previous section (3a)

when the reasons for establishing the 5-7 month desexing age were discussed and include:

- Early age anaesthesia and desexing is never going to be as safe as performing the procedure on an older and more mature dog. Regardless of how safe modern anaesthetics

have become, the liver and kidneys of younger animals are considered to be less mature

than those of older animals and therefore less capable of tolerating

the effects of anaesthetic drugs and less effective at metabolizing them and breaking them

down and excreting them from the body. Even though it is very uncommon, there will always be the occasional early age animal that suffers from potentially life-threatening

side effects, in particular liver and kidney damage, as a result of young age anaesthesia. Having said that, the

anaesthesia time is heaps quicker and blood loss is greatly reduced, so maybe it all balances out ...

- There is an increased risk of severe hypothermia (cold body temperatures) and

hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) occurring when young animals are anesthetized. This

hypothermia predisposition is caused by the young puppy's increased body surface area (larger area for heat to be lost), reduced ability to shiver and reduced body

fat covering (fat insulates against heat loss). The predisposition towards hypoglycemia is the result of a reduced liver ability to produce glucose from stores of glycogen and body fat, as well as the fact that these stores of fat and glycogen are smaller in the young animal.

- Loss of sex hormone production at a very early age, as a result of desexing, may

result in extremely immature development of feminine body characteristics. In particular, the animal's

vulva and mammaries will remain very small and immature. Vulval hypoplasia (a small, juvenile vulva)

may become a problem in overweight animals as they will often develop a roll of fat over their vulva which can

predispose them to vulval dermatitis, urine scalding and vulval skin infections (+/- urinary tract infections).

- Early neutering may result in retained juvenile behaviours inappropriate to the animal's age later on. A fully

grown dog with overly-playful puppy qualities pouncing up to another adult dog is likely to be misread by that other dog and bitten.

- Early neutering may result in urinary incontinence later on (but so can later neutering too).

- Early age neutering prevents dog breeders from being able to accurately determine which puppies will be valuable stud animals in the future (i.e. it is too early to tell when they are only pups). Because desexing equates to a loss of breeding potential and valuable genetics, many breeders choose to only desex their dogs after they have had some time to grow (after all, it is not possible to look at a tiny puppy and determine whether or not it will have the right color, conformation and temperament traits to be a breeding and showing dog). This allows the breeder time to determine whether or not the animal in question will be a valuable stud animal or not.

- Early spaying and neutering will not 100% reduce pet overpopulation and dumping problems when a large proportion of dumped animals are not merely unwanted litters, but purpose-bought, older pets that owners have grown tired of, can't manage, can't train and so on. Those people, having divested themselves of a problem pet, then go and buy a new animal, thereby keeping the breeders of dogs in good business and promoting the ongoing over-breeding of animals.

Author's note: at the time of this writing (2009), I was working as a veterinarian in a high

output animal shelter in Australia. Because shelter policy was not to add to

the numbers of litters being born irresponsibly by selling entire animals, all dogs, including puppies, were required to be desexed prior to sale. Consequently, it was not unusual for us to desex male and female puppies and kittens at early ages (anywhere from 8 weeks of age upwards). Hundreds of puppies and kittens passed under the surgeon's knife every year on their way to good homes

and I must say from experience that the incidence of intra- and post-operative complications that were a direct

result of underage neutering was exceedingly low.

4. Dog spaying procedure (dog spay operation) - a step by step pictorial guide to dog spaying surgery.

As stated in the opening section, dog spaying is the surgical removal of a female dog's internal reproductive organs. During the procedure, each of the female dog's ovaries and uterine horns are removed along with a section of the dog's uterine body. And, to be quite honest, from a general pet owner's perspective, this is probably all of the information that you really need to know about the surgical process of desexing a female dog.

Desexing basically converts this ...

Image: This is a preoperative picture of an anesthetized female cat, already clipped, just prior to cat spaying surgery

(our apologies for having a feline image on a dog page - Pet Informed will replace this image when a clipped dog photo is available).

The belly of a female dog just prior to dog spaying surgery would look similar after pre-surgical clipping.

... into this ...

Image: This is a photo of the same cat after her reproductive organs have been removed surgically. All you can see from the outside is a small suture in the middle of her belly. Similar stitches appear in the belly skin of

female dogs after they have been desexed.

... by removing these.

Image: This is a picture of a canine reproductive tract, which has been removed by sterilisation surgery. You can clearly see the ovaries, uterine horns and uterine body: these are the main sites of hormone production, ova/egg production and puppy development in the female animal.

For those of you readers just dying to know how it is all done, the following section contains a step by step

guide to the pre-surgical and surgical process of desexing a female dog (ovariohysterectomy procedure). There are many surgical desexing techniques available for use by veterinarians, however, I have chosen to demonstrate the very commonly-used "midline incision approach" of dog spaying. Diagrammatical images are provided to illustrate the process and I have included links to my

photographic step-by-step pages on cat spaying procedure (similar to dog spaying procedure) and pregnant cat spaying procedure.

Once again, Pet Informed apologizes for the use of feline spay surgery photographs in this section on dog spaying surgery. We will replace these images once dog spaying photos become available. The use of these cat spay images

to illustrate the points being made should not interfere with your understanding of dog spaying procedure as

the two spay procedures are almost identical in appearance.

DOG SPAYING PROCEDURE STEP 1:

Preparation of the animal prior to entering the veterinary clinic.

Preparation of an animal for any surgical procedure begins in the home.

Preparation of an animal for any surgical procedure begins in the home.

Your animal should be fasted (not fed any food) the night before a surgery so that she has no food in her stomach

on the day of surgery. This is important because dogs that receive a general anaesthetic

may vomit if they have a full stomach of food and this could lead to potentially fatal complications. The dog could choke on the vomited food particles or inhale them into its lungs resulting

in severe bacterial or chemical pneumonia (severe fluid and infection build-up within the air spaces of the lungs).

The dog should be fed a small meal the night before surgery (e.g. 6-8pm at night) and then not fed after this. Any food that the animal fails to consume by bedtime should be taken

away to prevent it from snacking throughout the night.

Young puppies and kittens (8-16 weeks) should not be fasted for more than 8 hours prior to surgery.

Water should not be withheld - it is fine for your canine pet to drink water before admission into the vet clinic.

Please note that certain animal species should not be fasted prior to surgery or, if they

are fasted, not fasted for very long. For example, rabbits and guinea pigs are not

generally fasted prior to surgery because they run the risk of potentially fatal intestinal paralysis (gut immotility) from the combined effects of not eating and receiving anaesthetic drugs. Ferrets have a rapid intestinal transit time (the time taken for food to go from the stomach to the colon)

and are generally fasted for only 4 hours prior to surgery.

If you are going to want to bath your female dog, do this before the surgery because you will

not be able to bath her for 2 weeks immediately after the surgery (we don't want the healing spay wounds to get wet).

Your vet will also thank you for giving him/her a nice clean animal to operate on.

DOG SPAYING PROCEDURE STEP 2:

The dog is admitted into the veterinary clinic.

When an animal is admitted into a veterinary clinic for desexing surgery, a number of things will happen:

- 1) You should arrive at the vet clinic with your fasted dog in the morning. Vet clinics usually tell owners what time they should bring their pet in for surgical admission and it is important that you abide by these admission times and not be late. If you are going to be

late, do at least ring your vet to let him know. Vet clinics need to

plan their day around which pets arrive and do not arrive for surgery in the morning. A pet turning up late throws all of the day's planning out the window. Do remember that your vet has the right to refuse to admit your pet for dog spaying surgery if you arrive late.

- 2) The animal will be examined by a veterinarian to ensure that she is healthy for dog spaying surgery. Her gum color will be assessed, her heart and chest listened to and her temperature taken to ensure that she is fit to operate on. Some clinics will even take your pet's blood pressure. This pre-surgical examination is especially important if your pet is old (greater than 7-8 years). In addition to the routine health check, your dog will also be examined in order to determine whether or not she is in-heat or pregnant.

If she is, the vet will discuss the added costs and risks of the dog spaying procedure with you and you can decide whether you want to continue with the operation or post-pone it.

- 3) You will be given the option of having a pre-anaesthetic blood panel done. This is a simple blood test that is often performed in-house by your vet in order to assess your dog's basic liver and kidney function. It may help your vet to detect underlying liver or kidney disease

that might make it unsafe for your dog to have an anaesthetic procedure. Better to know that there is a problem before the pet has an anaesthetic than during one! Old dogs (>8 yrs) in particular should have a pre-anaesthetic blood panel performed (many clinics insist upon it),

but cautious owners can elect to have young pets tested too.

- 4) The dangers and risks of having a general anaesthetic procedure will be explained to you. Please remember that even though dog spaying is a "routine" surgery for most vet clinics, animals can still die from surgical and/or anaesthetic complications. Animals can have sudden, fatal allergic reactions to the drugs used by the vet; they can have an underlying disease that no-one is aware of, which makes them unsafe to operate on; they can vomit whilst under anaesthesia and choke and so on. Things happen (very rarely, but they do) and you

need to be aware of this before signing an anaesthetic consent form. Remember that the risks

are greater with large-breed, obese, in-heat and pregnant animals.

- 5) You will be given a quote for the surgery. Remember that the costs of dog spaying

surgery will increase if your dog is in heat (in season) or pregnant.

- 6) You will be asked to sign an anaesthetic consent form. As with human medicine, it is becoming more and more common these days for pet owners to sue vets for alleged malpractice. Vets today require clients to sign a consent form before any anaesthetic procedure is performed so that owners can not come back to them and say that they were not informed of the risks of anaesthesia, should there be an adverse event.

- 7) Make sure that you provide accurate contact details and leave your mobile phone on so that your vet can get in contact with you during the day! Vets may need to call owners if a spaying complication occurs, if an extra procedure needs to be performed on the pet or if the pet has to stay in overnight.

- 8) Your dog will be admitted into surgery and you will be given a time to return and pick it up. It is often best if you ring the veterinary clinic before picking your pet up just in case it can not go home at the time expected (e.g. if surgery ran late).

DOG SPAYING PROCEDURE STEP 3:

The dog will receive a sedative premedication drug (premed) and, once sedated, it will be given a general anaesthetic and clipped and scrubbed for surgery.

The female dog is normally given a sedative-containing premedication drug before

surgery, which is designed to fulfill many purposes. The sedative calms the dog, making

it slip into anaesthesia more peacefully; the sedative often contains a pain relief

drug (analgesic), which reduces pain during and after surgery and the sedative action results

in lower quantities of anaesthetic drug being needed to keep the animal asleep. Depending

upon the premedication drug cocktail given, other specific effects may also be achieved including:

reduction of saliva production and airway secretions (this reduces drooling and the

risk that saliva and respiratory secretions may be inhaled into the lungs during surgery);

improved blood pressure; airway dilation (making it easier to breathe) and so on.

General anaesthesia is normally achieved by giving the dog an intravenous injection of

an anaesthetic drug, which is then followed up with and maintained using the same injectable

drug or, more commonly, an anaesthetic inhalational gas. The female dog has a tube inserted down its throat during the surgery to help it to breathe better; to stop it from inhaling any saliva or vomitus and to facilitate the administration of any anaesthetic gases.

The skin over the animal's belly is shaved and

scrubbed with an antiseptic solution prior to surgery.

Image: This is a picture of a cat's belly being scrubbed and cleaned with an antiseptic

scrub in preparation for cat spay surgery. A bitch being prepared for dog spaying surgery would have

her belly scrubbed in a similar fashion.

The surgery:

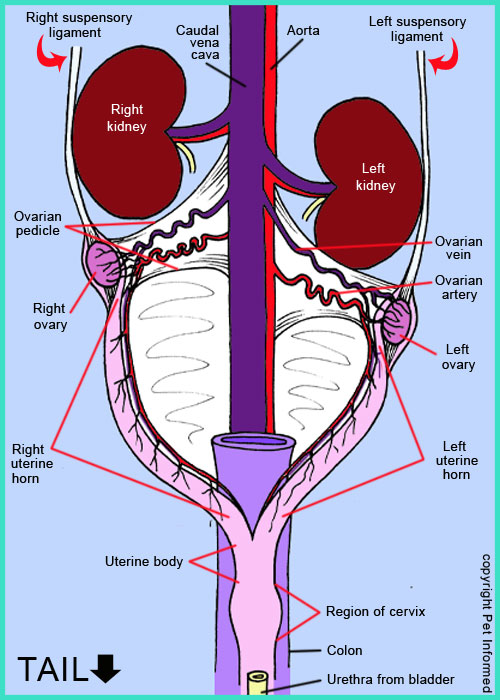

In order for you to properly understand the process of dog spaying surgery, I have to take a second to explain the anatomy of the female dog's reproductive organs.

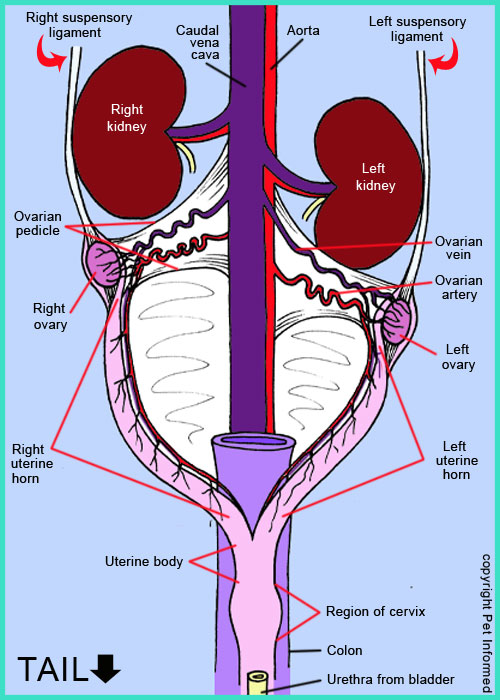

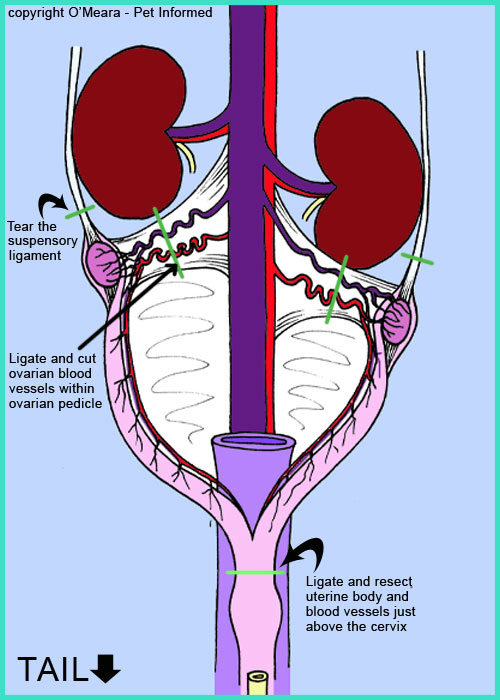

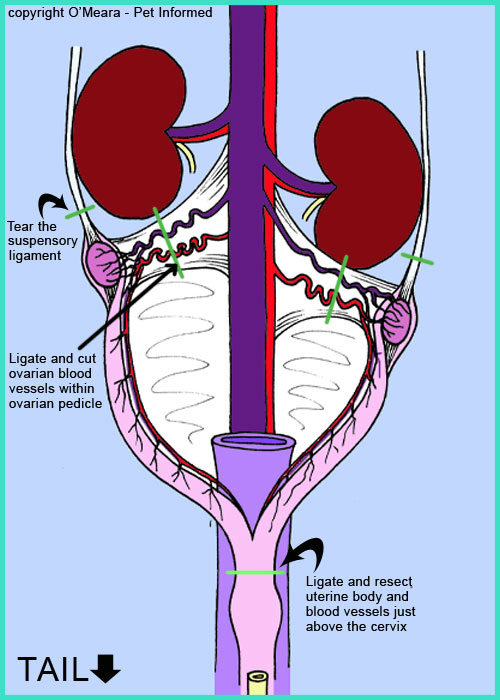

Image: This is a diagram of the reproductive anatomy of a female dog as it appears when

the abdomen is incised and entered from the abdominal midline. I have not drawn in the canine intestines or bladder (aside from the stump of the bladder neck - bottom), which would normally overlie the animal's reproductive structures when the animal is positioned on its back (the

reproductive organs occupy the roof of the abdomen, near the animal's spine and kidneys).

Of particular importance, when it comes to canine spay surgery, are the fatty ovarian pedicles (the tubes of

dense fat and connective tissue containing the ovarian arteries and veins) and the uterine body, just ahead of the animal's cervix. These are highly vascular sites that must be tied off securely with sutures (so that they do not bleed) and cut in order for the uterus and ovaries to be removed.

In the female dog, unlike the female cat, the ovaries are held down firmly into the abdominal cavity by tight bands of ligamentous tissue, called the right and left suspensory ligaments (these are indicated in the above image). In order for the veterinary surgeon to safely access and tie-off the dog's ovarian pedicles, these suspensory ligaments must firstly

be broken to allow the ovaries to be raised up out of the abdomen and into view. Breaking these

ligaments can be difficult in dogs, particularly large dogs, adding to the risk of ovarian pedicle tearing and hemorrhage

in this species (compared to the cat, where such risks are much lower).

This risk of hemorrhage is made much greater when in heat or pregnant dogs are spayed (their ovarian pedicle

vessels are bigger and more fragile) or when very obese, large breed dogs are spayed (their ovarian

pedicles are imbedded in thick fat making them difficult to visualise even when the suspensory ligaments are

broken correctly).

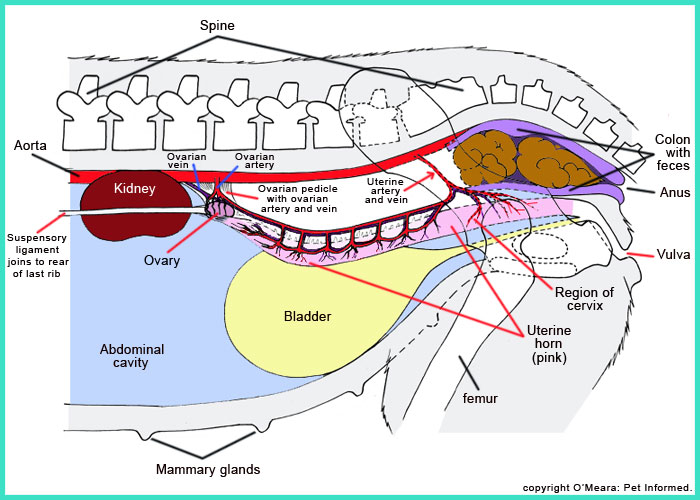

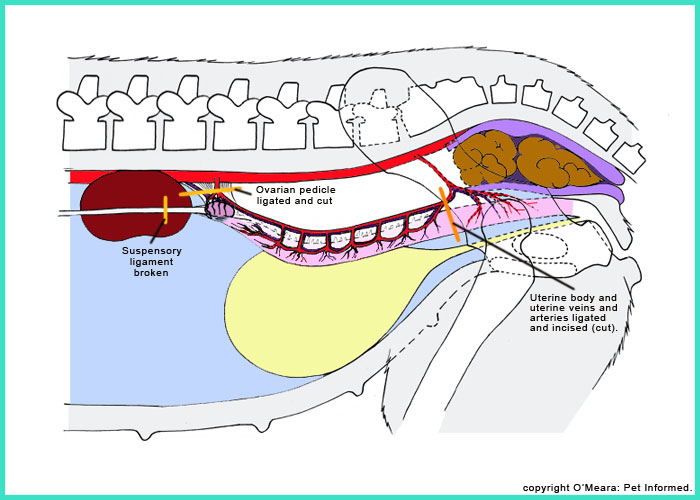

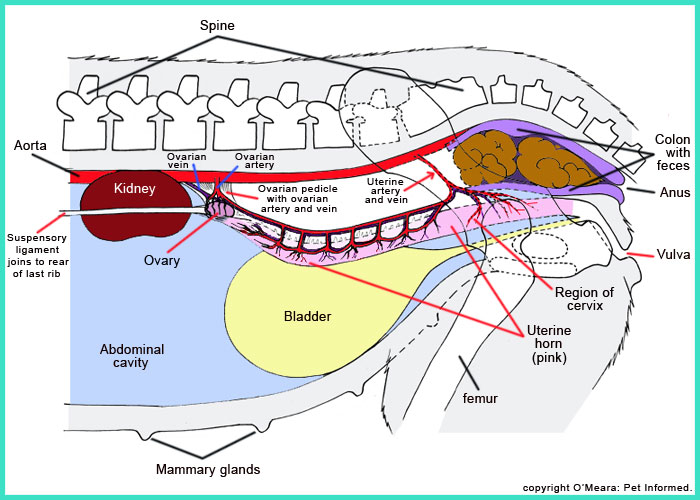

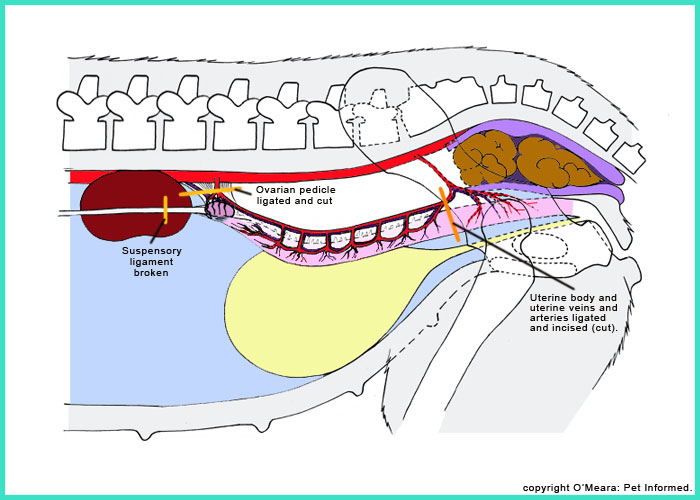

Image: This is a diagram of the reproductive anatomy of a female dog as it appears from the

side. I have drawn this view in order to give you a three-dimensional idea of where the uterus sits in the dog (it is located very high within the abdomen). This is the anatomy that would be encountered if the veterinarian performed a flank spay

(a spay technique whereby the veterinarian enters the animal's abdominal cavity via an incision made

through the muscles of the animal's flank). I have not drawn in the intestines or colon (aside from the stump of the colon/rectum), which would take up most of the anterior blue space

indicated in this diagram.

Of particular importance, when it comes to canine spay surgery, are the fatty ovarian pedicles (the tubes of

dense fat and connective tissue containing the ovarian arteries and veins) and the uterine body, just ahead of the animal's cervix. These are highly vascular sites that must be tied off securely with sutures (so that they do not bleed) and cut in order for the uterus and ovaries to be removed.

In the female dog, unlike the female cat, the ovaries are secured firmly into place within the dorsal (upper) abdominal cavity by tight bands of ligamentous tissue, called the right and left suspensory ligaments (these are indicated in the above image). In order for the veterinary surgeon to safely access and tie-off the dog's ovarian pedicles, these suspensory ligaments must firstly

be broken to allow the ovaries to be raised up out of the abdomen and into view. Breaking these

ligaments can be difficult in dogs, particularly big dogs, adding to the risk of ovarian pedicle tearing and hemorrhage

in this species (compared to the cat, where such risks are much lower).

This risk of hemorrhage is made much greater when in heat or pregnant dogs are spayed (their ovarian pedicle

vessels are bigger and more fragile) or when very obese, large breed dogs are spayed (their ovarian

pedicles are imbedded in thick fat, making them difficult to visualise, even when the suspensory ligaments are

broken correctly).

DOG SPAYING PROCEDURE STEP 4:

The skin is incised and the dog's abdomen entered.

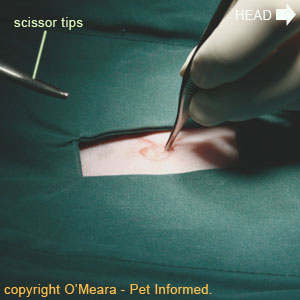

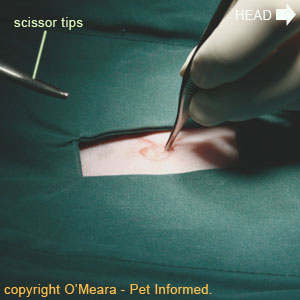

Photograph 1: This is a picture of a small incision line being made in the skin of a young cat being spayed. You'll notice that the incision line is very small (approx 1 cm long)

and that it is being made approximately 1 inch below the animal's umbilical scar on the abdominal midline.

In dog spaying surgery, however, the skin incision line is generally a lot longer than in the cat

(anywhere from 2-6cm or more, depending on the size of the dog) and it is generally started further forwards on the abdominal midline, right behind the dog's umbilical scar.

Picture 2: In this image, the veterinary surgeon is removing some of the fat (termed subcutaneous fat, sub-q fat or SC fat) from the incision line region. The fat is the white, shiny substance in the center of the incision line.

There is generally a lot of fat located between the animal's (cat or dog) skin and its abdominal wall

muscles. The veterinarian will often cut a small amount of this fat away, allowing easy access to

and visualisation of the cat or dog's abdominal wall muscles.

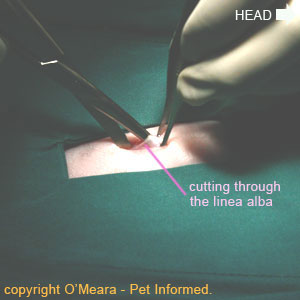

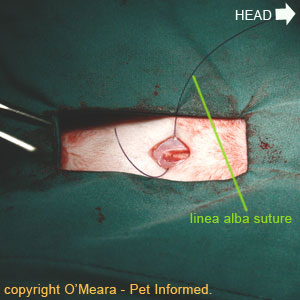

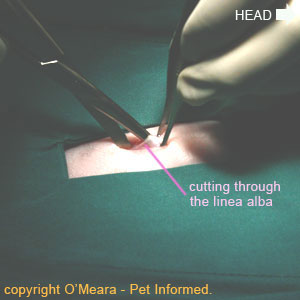

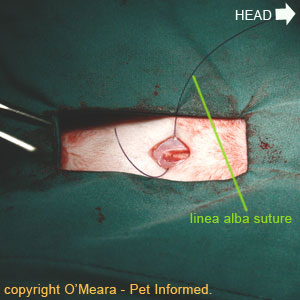

Image 1: The veterinarian enters the cat or dog's abdominal cavity by cutting through the abdominal

wall musculature on the midline of the abdomen. The veterinarian aims to cut along a central line of scar tissue that joins the right and left sides of the animal's abdominal wall musculature. This line of scar tissue is called the linea alba (literally meaning - "white line").

By cutting through scar tissue, rather than the red muscle located either side of the linea alba, the veterinarian reduces the amount of bleeding incurred in entering the pet's abdominal cavity.

By cutting through scar tissue, rather than the red muscle located either side of the linea alba, the veterinarian reduces the amount of bleeding incurred in entering the pet's abdominal cavity.

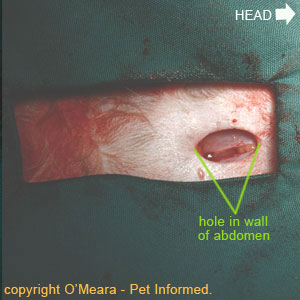

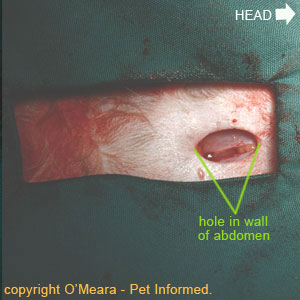

Photograph 2: This is a close-up picture of the incision line after the linea

alba has been incised. You can see the hole going into the abdominal cavity.

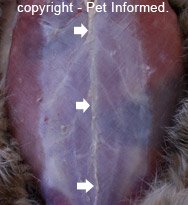

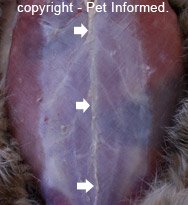

Photo 3 (right): This is a post-mortem image of a cat's abdominal wall muscles (the image would be the same

if the animal were a dog). The skin has been removed and the linea alba (white line - indicated with arrows) is clearly visible.

DOG SPAYING PROCEDURE STEP 5:

The ovarian pedicles and uterine body are ligated (tied off) and cut and the uterus and ovaries are removed

from the abdomen.

Image: This is the same diagram that I presented earlier, showing the reproductive

anatomy of the female dog. In this diagram, the sections of the reproductive anatomy that are ligated (tied closed with sutures) and incised (cut through) are indicated with green lines. This tying-off and cutting procedure needs to be performed with great care, otherwise there is the risk of severe internal bleeding occurring or a section of ovary being left behind (ovarian remnant), which could result in the animal returning to heat (showing signs of heat) after it has been 'desexed'.

Author's note: In the case of dog spaying surgery, the right and left suspensory ligaments

are very important. These ligaments need to be broken in order for the canine ovarian pedicles

(ovarian arteries and veins) and ovaries to be accessed, ligated and transected (cut).

Image: This is the same diagram that I presented earlier, showing the reproductive

anatomy of the female dog when taken from a side-on (lateral) vantage point. In this diagram, the sections of the reproductive anatomy that are ligated (tied closed with sutures) and incised (cut through) are indicated with orange lines. This procedure needs to be done with great care

otherwise there is the risk of severe internal hemorrhage occurring or a section of

ovary being left behind (ovarian remnant), which could result in the animal returning to season

(showing signs of heat) even though it has been 'desexed'.

SPAYING A DOG PROCEDURE STEP 6:

The dog's abdominal wall is sutured closed.

Pictures: After the uterus and ovaries have been removed, the surgeon uses absorbable suture material to close the hole in the dog's abdominal wall musculature (linea alba). Because the linea alba is essentially a tendon-like, collagenous structure (made of collagen), it has less blood supply than red muscle and, therefore, takes longer to heal than muscle would. To take this slower healing into account, the veterinarian often uses a longer-lasting suture (a suture

that is slower to lose its strength and slower to absorb) to close the linea alba. Because

this suture absorbs over time, the vet does not have to remove it later on.

Image:The linea alba has been sutured closed.

DOG SPAYING PROCEDURE STEP 7:

The subcutaneous fat layer is sutured closed.

Photo: The subcutaneous fat layer (also called the SC or sub-q layer) is sutured closed. This layer closure acts to reduce the amount of open space (called 'dead space') located between the animal's abdominal wall and skin layers, thereby reducing the risk of a large, fluid-filled swelling

(called a seroma) forming at the surgery site. Basically, whatever space/gap you leave in a surgery site, fluid

will pool in - by closing down this open space (dead space), the vet surgeon essentially

leaves fewer sites available for inflammatory fluids to pool in.

SPAYING FEMALE DOGS PROCEDURE STEP 8:

The skin layer is sutured closed.

Images: The surgeon is closing the skin using non-absorbable skin sutures. These

will need to be removed in 10-14 days.

Image: Absorbable skin sutures can also be placed. These are called intradermal sutures

and they do not need to be removed. They look like a line with no suture material showing.

They are useful because dogs find it harder to chew them out. These skin sutures are particularly useful when

closing the skin incisions of aggressive dogs or dogs on remote properties because there is no need for the dog to return to the clinic to have the sutures out.

A Photographic Guide to Cat Spay Surgery:

If you would like to view a complete, step-by-step, photographic guide to feline

desexing surgery, please visit our great Cat Spay Procedure page. Although it is not a dog spaying

page per se, it should give you some idea of the process involved in performing a dog spay surgery

since the two spay procedures are almost identical to each other.

A Photographic Guide to Spaying a Pregnant Cat:

As will be discussed in the FAQs and Myths section (section 8), it is possible to desex a

female dog or cat who is already pregnant. What should be understood, however, is that the desexing

of pregnant animals carries with it a much higher risk than the desexing of non-pregnant

females does (the ovarian and uterine blood vessels are much larger and bleed a lot more and the uterus

itself is greatly enlarged and much more friable and prone to tearing apart, compared to the non-pregnant

uterus). In viewing this page (which does contain images of surgical abortion) what should

be clear to you is that there is added danger and risk and pain (a bigger surgical incision) to the female animal in desexing her whilst she is pregnant and that, for this reason, the emphasis should

be placed on having a female dog or cat desexed well before she manages to become pregnant. If you would like to view a complete, step-by-step, photographic guide to pregnant cat spaying surgery (which is, again, similar to pregnant dog spaying surgery), please visit our informative Spaying a Pregnant Cat page.

5. Dog Spaying After Care - all you need to know about caring for your female dog after dog spaying surgery.

When your dog goes home after dog spay surgery, there are some basic exercise, feeding,

bathing, pain relief and wound care considerations that should be taken into account to improve your

pet's healing, health and comfort levels.

1) Feeding your dog immediately after dog spaying surgery:

After a dog or puppy has been spayed, it is not normally necessary for you to implement any

special dietary changes. You can generally go on feeding your pet what it has always eaten. Some owners, however, like to feed their pets bland diets (e.g. boiled, fat-free, skinless chicken and rice diet

or a commercial prescription intestinal diet such as Royal Canin Digestive or Hills i/d)

for a few days after surgery in case the surgery and anaesthesia process has upset their tummies. This is not normally

required, but it is perfectly fine to do.

Unless your veterinarian says otherwise, it is normally fine to feed your dog the night after

surgery. Offer your pet a smaller meal than normal in case your pet has an upset tummy

from surgery and do not be worried if your pet won't eat the night after surgery.

It is not uncommon for pets to be sore and sorry after surgery and to refuse to eat that evening.

If your dog is a bit sooky and won't eat because of surgery-site pain, feel free

to tempt her with tasty, strong-smelling foods to get her to eat. Warmed skin-free roast chicken

often works well and it is not too heavy on the stomach. Avoid fatty foods such as mince, lamb, pork and processed meats (salami, sausages, bacon) because these may cause digestive upsets.

Be aware of your pet's medications and whether they need to be given with food. Some dogs

go home on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as Carprofen

(trade names include: Prolet, Rimadyl, Carprofen tablets), Firocoxib (tradenames include

Previcox) and Meloxicam (tradenames include Metacam)

after surgery. These drugs (with the exception of Previcox) need to be given with food. Do not give these drugs if your dog is refusing to eat.

Most dogs that get spayed are not normally off their food for more than a day. You should contact your vet if your pet does not eat for more than 24 hours after surgery.

2) Exercising your dog after dog spaying:

It takes 10-14 days for skin wounds to heal after surgery; even longer for the linea alba wounds to heal. It is therefore recommended that running-around exercise be avoided or minimized for a minimum of 2 weeks after surgery to allow the skin the best chance of staying still and healing. Restricting

your dog's exercise will also reduce the risk of a large seroma forming (section 6b) and

reduce post-operative spay-site pain.

Of course, many of you scoff at the idea of "keeping a puppy rested and still!" It is, therefore, normally fine if your puppy romps around quietly inside your house and performs its normal,

quiet indoor activities and play (no running around madly and jumping on and off couches, of course!). I would, however, avoid letting your dog

go outside off-lead until she has had time to heal (14 days minimum). This is especially important

if the pup is of the energetic, boisterous kind (in contrast, an old, quiet dog more fond of sleeping

in the shade might be fine to allow outside). Keeping the animal indoors or in a non-dirty confined space (e.g. a small dog run)

will prevent excessive exercise, which could impede healing, and it will also prevent the canine spay wounds from becoming wet or