Time To Say Goodbye: A Practical Guide to Pet Euthanasia (Having Your Pet Put Down).

The difficult decision to "put down" or euthanase (euthanatize) a beloved family petis an issue all too often faced by pet owners and their veterinarians. The simple truth is that most pets do not have a massive lifespan (3-6 years for rodent-type animalsand up to about 20-25 years for exceptionally long-lived individual dogs and cats)and we humans often outlive them many times over. Consequently, most people who take on thelove and joy of owning a companion animal will at some point need to face the sad realities oftheir furred, scaled or feathered friend's mortality and perhaps need to considermaking the ultimate sacrifice: having their pet humanely killed in order to relieveits suffering and/or pain.

The difficult decision to "put down" or euthanase (euthanatize) a beloved family petis an issue all too often faced by pet owners and their veterinarians. The simple truth is that most pets do not have a massive lifespan (3-6 years for rodent-type animalsand up to about 20-25 years for exceptionally long-lived individual dogs and cats)and we humans often outlive them many times over. Consequently, most people who take on thelove and joy of owning a companion animal will at some point need to face the sad realities oftheir furred, scaled or feathered friend's mortality and perhaps need to considermaking the ultimate sacrifice: having their pet humanely killed in order to relieveits suffering and/or pain.

This page gives you, the owner, a complete practical guide to the euthanasia of pet animals. As a veterinarian, I have had a lot of experience putting animals down and this guide is written based uponthose experiences. This page covers: the practicalities and methods of euthanasia itself;what you (the owner) can expect to have happen when a pet is put down; ways to help youmake the decision or know when to have a pet put down; tips for making the process 'easier' on you emotionally; options for dealing with pet bodies; what to say to the children and how to treat the pets 'left behind'.

The euthanasia topics are covered in the following order:

1) What is euthanasia? - a basic definition and summary overview of what putting down a pet entails.

2) Reasons for euthanasia: why people euthanase (euthanatise) pets or livestock:

2a) Valid reasons for putting an animal down.

2b) Not so valid reasons for putting an animal down.

3) How to decide when it is time to put a pet animal (e.g. cat or dog) down?:

3a) How will I know that it is time to euthanase? - hints and tips on how and when to make that hard decision.

3b) How to recognise that a pet is in pain.

3c) I just want to let my pet die at home - is this okay?

3d) I just want a few more days with my pet at home before putting him or her down - what are my options?

3e) Why won't my veterinarian just tell me when to put down my pet?

4) The euthanasia process itself:

4a) What euthanasia methods are available to vets for putting down domestic animals?

4b) Euthanasia procedure: how is euthanasia solution given to pets? - this section contains detailed, specificinformation on how humane euthanasia is performed on dogs, cats, mice, rats, gerbils, guinea pigs,rabbits, birds, ferrets, reptiles, fish, horses and livestock animal species.

4c) Is euthanasia painful?

4d) Is euthanasia instant?

4e) What can I expect to see/happen as my pet dies?

4f) How can I tell if a pet has died? What are the signs a pet is dead?

4g) Are there times when routine pet euthanasia takes longer or is more distressing?

4h) Do I need to be in the room with my pet to have it put down? Am I a bad owner if I don't stay?

4i) A step-by-step explanation of a typical euthanasia procedure in a veterinary clinic - thissection provides detailed info on euthanasia logistics (where it will be done, how each step is performed and in what order, paperwork that needs to be filled in and so on).

5) Hints and Tips to help you cope better on the day - making the process of pet euthanasia a little easier.

6) What should I do with my pet's body?

6a) Burial at home.

6b) Pet Cemeteries.

6c) Cremation.

6d) Leaving the body with the vet - what happens to it?

6e) Can I leave the body to science?

6f) Can my pet's body be of use (e.g. organ donation, blood donation) before he or she dies?

6g) What if I can't decide what to do with the body right now - can my vet hold the body until I decide?

7) Frequently asked questions (FAQ) about pet euthanasia and your children:

7a) Should I bring my kids to witness the euthanasia of their pet?

7b) What can I explain to the kids about death?

8) What about my remaining pets?

8a) Will my other dog (or cat) grieve? What are the symptoms of grieving?

8b) How should I treat (behave around) the remaining animal/s after this one has died?

8c) Should I let my other pet/s see the dead body?

Author's note: Please note that it is not possible for one online web pageand one author to cover every single facet and argument about euthanasia that is out there, in particular the religious morals, ethics, 'rights and wrongs' and 'pros and cons' of the euthanasia procedure. The decision to put down a pet is a very private, individual process that each owner must go through or decide upon on his or her own. Opinions about this process; how it should bedone; when it should be done and even if it should be done vary with an individual's past experiences, religious beliefs and emotional capacity for the idea. There is no one right or wrong on this matter: whilst there are many 'pros' to the euthanasiaargument, there are just as many 'cons of euthanasia' on the other side of the euthanasiadebate. As one author, I can only present this subject and its facts as I personally see them and, because of this, I can not possibly hope to satisfy and please everybody. For example, just the thought of pet euthanasia at all is abhorrent in some quarters and so, naturally, this page will be distasteful to those readers. Some of the information I write here may even be disagreed upon by some other vets and individual animal health or welfare professionals with differing viewpoints to my own. I accept this. All opinions, arguments and disagreements are perfectly valid: euthanasia is, as I've said, a very individual,personal thing. If any of the stuff I write here offends you or is contrary to what youbelieve, please understand that it is never my intention to cause any such offense and that you have my sincerest apologies up front.

WARNING - IN THE INTERESTS OF PROVIDING YOU WITH COMPLETE AND DETAILED INFORMATION, THIS SITE DOES CONTAIN MEDICAL AND SURGICAL IMAGES THAT MAY DISTURB SOME READERS.

1. What is euthanasia?

Euthanasia is the process whereby an animal is deliberately killed (usually by aveterinarian or other animal industry professional qualified to do the job) for reasonsof humane relief of suffering; uncontrollable behavioural defects (e.g. aggression, inability to tame, extreme toileting misbehavior); population control; disease control and/or personal financial limitations.

Typical humane euthanasia procedure:

During the process of euthanasia, the animal patient is normally injected with a chemical substance (called pentobarbitone) that is very closely related to some of the drugsnormally used to induce general anaesthesia in animals. This chemical essentially acts like a severe overdose of veterinary anaesthetic: it enters the animal's blood streamand suppresses the function of the animal's heart and brain, causing instant loss of consciousness and pain sensation and stopping the beating of the animal's heart, therebycausing death whilst the animal is deeply asleep. This is where the term "put to sleep" comes from. The animal peacefully and instantly falls asleep (undergoes anaesthesia) and then passesthrough into death without experiencing any pain.

Alternative euthanasia methods and procedures:

Occasionally (rarely), pet euthanasia may be performed using alternative methods to pentobarbitoneinjection. Euthanasia can be performed on an animal via the administration of large volumesof potassium chloride: this causes the animal's blood potassium levels to rise to critical levels, resulting in the animal dying from heart arrhythmia (sort of like a fatal, severe heart palpitation in people). Because potassium chloride injection is painful, the animal is normally placed under a general anaesthetic before the solution is injected. Some euthanasias may even be performed using such means as shooting(euthanasia by gunshot); captive bolt pistol (a form of shooting that does notinvolve a bullet); gassing (carbon monoxide or carbon dioxide); decapitation; neck-breaking (cervical dislocation); throat-cutting (exsanguination) and electrocution. None of these alternative euthanasia methods is generally used in the putting down of domestic pets (most are far too distressing for owners to watch), however, shooting, potassium chloride administration and captive bolt euthanasia may sometimes be used in the humane euthanasia of horses and livestock animals. Gassing, decapitation and electrocution are more likely to be used in the killing of poultry or pigs for human consumption, however, this would technically be termed slaughter rather than euthanasia.

2) Reasons for euthanasia - why people euthanase (euthanatise) pets or livestock:

People elect to have their pets and other domesticated animals put down for a huge variety ofhumane, personal, practical and financial reasons. I have chosen to list some of the more commonreasons why people elect to euthanase animals (I could never hope to list them all!) under two headings: valid reasons for putting an animal down (section 2a) and not-so-valid reasonsfor putting an animal down (section 2b).

By dividing up this section into these two subsections, so named, I have naturally opened myself up to some criticism from those of you who think that some of my 'valid reasons' are not valid at all andthose of you who think that I might be being too harsh in my choice of the 'not-so-valid'. Please note thatthe information contained within these two subsections is just my own opinion (I have provided reasons for my opinion in each subsection listing) and that this opinionis not at all set in stone: every animal, owner and personal situation is different and some of my not-so-valid reasons may be perfectly valid given an individual person's situation.

2a) Valid reasons for putting an animal down.

The following is a list of reasons that I consider to be valid reasons for havinga dog or cat or other animal euthanased. Please note that this is not an exhaustive list.

The animal is suffering from a terminal illness that medical or surgicaltherapy can no longer relieve or help:

The relief of pain and suffering is probably the most common reason owners have for euthanasing a beloved pet. Because animals are now living long enough (just like people)to die slowly by degrees from chronic, incurable, sometimes-painful illnesses like cancer, renal disease and heart failure, it is becoming very common for owners to have to make this choice about what is kindest for their terminally ill pets.

It is important to note that not every animal that develops or is diagnosed with a terminal illness needs to be put down right away. There are many owners who hear the words 'cancer' and 'kidney failure' and 'heart failure' and panic, thinking that their pet needs to be put down right away, when the reality is that some of these animalscan often tick along for months or even years, with the right medications and diets, andeven have a good quality of life. As long as these animals are not suffering; arenot in unmanageable pain and are performing all of their normal functions adequately (eating, drinkingand toileting normally and not losing excessive amounts of weight), then it is generally fine to keep them going.

The decision to euthanase is indicated when the animal is starting to suffer as a result of its incurabledisease and drugs are no longer available or enough to help relieve this suffering. Examples of this include: animals with heart failure and/or chronic lung disease (e.g. cancer) that are constantly distressed and anxious because they can not breathe easily; animals that are constantly in pain due to an enlarging tumour; animals that are constantly in agony from lesions in the bones or joints (e.g. bone cancer, severe arthritis); animals that are always vomiting, diarrheaing and suffering from intestinal pain and upset as a consequence of severe intestinal disease orulceration caused by chronic renal or liver failure. In these kinds of cases, itis often much kinder to put the animal out of its misery using veterinary drugsthan it is to force the animal to go on until it eventually dies in agony from its disorder.

The animal is suffering from a severe illness whereby survival and recovery is possible,but of minimal likelihood, and the animal is likely to go through significant pain and suffering while attempts are made to correct the problem:

Because animals, unlike humans, are unable to give any consent about the procedures that are performed on them, performing a large, painful surgical procedure on an animal or exposing that animal to long periods of severe illness, hospitalization stress and repeated medical procedures, in the remote chance that there will be recovery, must be weighed up very carefully. Human patients have a choice about how much pain they are willing to suffer for the remote chance of a cure and they also have a better cognitive understanding of what will be included in that care (prolongedhospitalisation, the use of ventilatory assistance, nausea-inducing medications and so on). Animals, on the other hand, do not have this understanding and so we(vets and owners) are the ones that must act on their behalf and in their best interests. Sometimes the pain and suffering involved in the care and attempted cure of an animal patient is simply not worth the very small chance there will be of a good outcome. This is a valid reason for an animal to be put out of its misery.

A good example of this is seen in the condition: feline aortic thromboembolism or FATE. FATE is a condition normally seen in cats whereby a large blood clot (thrombus) gets lodged in the arteries supplying the legs (usually the hind limbs) of the cat, thereby blocking the flow of oxygen and nutrients to the animal's limbs. The cat's legs, deprived of oxygen, immediately start to burn terribly and excruciatingly from a build-up of lactic acid; the affected limbs become cramped and rigid and eventually, if the clot persists, the cells of the limbs (muscles, connective tissues etc.) will start to die. You can only imagine how painful this is for the cat. Aside from the pain, the potassium and cell breakdown chemicals (e.g. myoglobin from muscles) released from these injured and dying cells also cause the cat to become very unwell: for example, large quantities of these chemicals flowing through the bloodstream places the cat at very high risk of developing acute renal failure.

Although there are treatments available for this condition, all aimed at supporting the cat whilst itsbody attempts to break down the blood clot, the reality is that the chances of the blood clot being dissolved are only around 30%; the cat will be forced to go through many days of agony whilst treatment (successful or unsuccessful) is occurring and the chances of anew clot forming within the year, should clot dissolution be successful this time, are over 80%. For all of these reasons, many veterinarians and cat owners elect to euthanasecases of FATE, rather than persist with them and put them through many days of suffering.

The pet has a chronic, manageable illness requiring a lot of medication (e.g. many pills and needles), regular hospital stays and frequent testing and veterinary check-ups to manage it, but the animal is behaviorally and emotionally ill-equipped to cope and gets far too distressed by all of the procedures to keep on having them done over and over again for the rest of its life.

As mentioned in the above section, pets can not give their consent for any of thethings that we do to them (e.g. surgery, chemotherapy, diabetes therapy). Some animalswith long-term manageable medical conditions such as diabetes and chronic renal failure becomeso fed up with being in hospital and being needled for blood or fluids or medication administrationall the time that they become savagely aggressive and needle shy and require a vet to sedate them or anesthetize them just to do any little thing with them. I sometimes think that, with these chronic, long-term, high-maintenance medical conditions,the trying to save the pet and treat it may not be worth the stress inflicted upon the animal in trying to do so.

The pet has a severe, chronic disease where death from the disease itself is unlikely, but drugs are no longer helping the pet with its pain or mobility.

There are certain chronic disease conditions whereby the animal is unlikely to dieas a result of the condition per se, but is in such severe, chronic, continuous pain orso debilitated (e.g. unable to move very far, unable to stand up) or so unable to maintain its hygiene and dignity that it can no longer be said to have any decent quality of life. In these cases, euthanasia is a viable option.

Author's note: The idea of what constitutes a "quality of life" for an animal and whatimportance "dignity" plays to an animal differs from owner to owner and pet to pet. The factors that make up "quality of life" for any one animal may be far removed from what makesup "quality of life" to a man or even to another individual animal of the same ordifferent species. Many humans would consider it a fate worse than death to beleft blind and/or deaf and yet a dog or cat may cope just fine. Some dogs are perfectly content being able to shuffle back and forth from kitchen to living room, whereas other dogs become depressed if they are no longer able to walk around the block or retrieve a ball. Some owners simply can not bear the thought and indignity of their pet soiling itself and lying in its urine or faeces, whereas other owners are happy to accept these accidents and happy to routinely bathe and clean their pet's bottom.

Probably the best example of this point is degenerative joint disease, otherwise known as arthritis or DJD. Arthritis by itself is not a terminal disease (crumbling, stiffening joints will not kill an animal), however, it has huge implications for the sufferer and is a common reason why many owners have their dogs, particularly large breed dogs, euthanatized. Animals with severely arthritic joints are often in discomfort most of the time. These animals are often subdued and reluctant to move and mayeven be prone to aggression because of this chronic, aching pain. Although these animals can often be managed with pain-relieving drugs, the effect of these drugs is often transient, becoming less effective as time wears on and the animal's condition progresses. In addition to this pain, the animal's mobility is often severely affected. The pet can not walk very well because its joints are fused and stiff; it becomes depressed because it can not join in on the fun things it usedto enjoy (e.g. walks, ball chasing); it often has trouble getting onto its feet to urinate and defecate (this can result in the animal soiling itself and becomingfly struck and maggot-ridden in summer) and the owners of large breed dogs often have great problems lifting these dogs up to clean them and/or help them to go outside. Eventually, the animal's pain and poor quality of life results in these owners putting the pet down.

The animal is exhibiting severe aggression.

Aggression, particularly regularly-occurring, non-provoked aggression, in dogs and cats and even rabbits, horses and livestock animals is a very valid reason for destroying theseanimals. This aggression may be towards people, other pets in the household or otheranimals outside of the household (e.g. livestock killers).

Whether an animal needs to be put down after its first act of aggression is debatableand you should discuss the matter with your veterinarian or an animal behaviouralistif it occurs. Some instances of aggression only occur the once because of circumstances occurring at the time and may not require euthanasia (e.g. a dog that has a snap because a person stepped on its tail or kicked it); some forms of aggression are highly situation specific and may not require euthanasia (e.g. if we put down everydog or cat that showed aggression towards vets, there wouldn't be many patients leftto treat); some forms of aggression can be easily treated with behavioural modification and training, whereas certain other forms of aggression only get worse with time and do require the pet to be put down (e.g. psychotic, unprovoked aggression due to various brain diseases).

Author's note: Animals (especially medium to large breed dogs) that attack and wound adult humans and children, regardless of whether the attack was provoked or not, are often required to be destroyed for this aggression under the law. Society can not risk having a person-aggressive dog being allowed a chance to do it again.

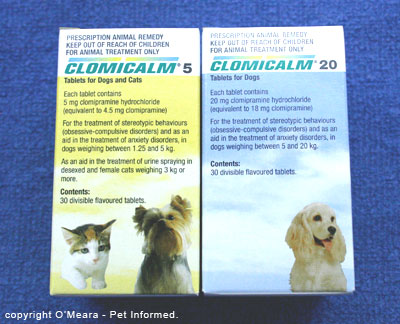

The animal has a severe behavioural condition that has not responded to veterinaryand/or behavioural modification therapies:

Some forms of behavioural disturbance are so severe that they are not conducive to apet remaining in a household. Examples include: pets that insist upon toileting allover the house; pets that bark all the time; pets that display severe aggression or guarding tendencies; pets with severe separation anxiety that results in them regularly destroying the householdin your absence (scratching down walls and doors etc.) and fence-jumper pets that constantly escape fromtheir yards and roam. If these behaviors persist despite veterinary attention and behaviouralistconsultation and all of your best efforts at re-training the animal and altering its environmentto suit (e.g. building better fences), then euthanasia may well be the only solution to the problem. It is probably not fair to try to rehome animals with severe behavioural defects because this rehoming will just place stress on an already stressed animal and pass the problem on to another person (certainly you should warn the potential owner about the problem before passing the pet on).

Heard health and disease eradication programs:

Selective euthanasia is sometimes used in breeding colonies, in addition to desexing, as a means of eradicating genetic diseases or negative traits. Whether this is a humane or valid thing to do really depends on the nature of the defect itself. Euthanasia of animals to remove defects that will be detrimental to the survival of that animal, breed or species may well be warranted (e.g. the euthanasia of Dobermann pinchers with severe von Willebrand's disease or young German Shepherds with severe hemophilia - both genetically-spread blood clotting disorders). Euthanasia of animals because their coat pattern is no good in the show ring is not warranted: these animals can be desexed and sold 'pet-only' to a nice home.

The use of euthanasia as a means of eradicating infectious diseases (especially highly-contagious diseases and/or highly environmentally-resistant diseases) in a large animal population such as a shelter, breeding or animal production colony is often done. For example, litters of puppies afflicted with canine parvovirus are typically euthanased by most shelters, rather than being treated, because the prognosis is so guarded and the risk ofcontaminating the entire facility (and thus killing other dogs) so high. Sometimesthe sacrifice of some is required for the greater good of the rest.

Notifiable diseases of high risk to human lives, animal lives and the economy:

Animals that contract diseases, normally infectious diseases, which are of a high safety risk to man and other animals (e.g. rabies, bird flu, Anthrax) are generally put to sleep. Animal herds that contract exotic diseases that may or may not necessarily be fatal, but which are of massive economic consequence to the affected country (e.g. foot and mouth, Newcastle disease virus (NDV), Blue Tongue Virus and many more) are usually culled, along with the animals on surrounding farms, to preserve the country's livestock and animal production and export industries.

Financial euthanasia - the pet has a life-threatening and/or costly-to-treat disease and the owner simply can not afford life-saving surgical or medical treatment:

The concept of financial euthanasia is probably the one reason given for euthanasia where peoples' opinions are most polarised and where vets and their clients most commonly clash. Some people consider finances to be a completely inexcusable grounds for killing a petand are outraged that vets will not provide services for free and/or that non-financialowners will even consider this option instead of going into debt for their animals. Other people and most veterinarians consider financial limitations to be a perfectly reasonable grounds for euthanasia of an animal (how reasonable we think it is does dependon the situation - I have made further mention of when financial euthanasia may be unacceptable in section 2b). Certainly, financial limitation is one of the most common reasons I have personally encountered for the putting down of domestic pets, although I must add that this finding would probably vary from practice to practice, depending on the area (affluent suburbs would potentiallyhave a lower incidence of financial euthanasia) and the situation (e.g. financialeuthanasia is common in emergency center practice because the animals are sicker and the treatment costs are much higher).

Arguments and opinions for and against financial euthanasia.

There are two main sides to the argument, both valid, and they are as follows:

The people who think financial limitations are not a valid reason to put down an animal at all:

In my experience, many of the people who claim that money should never be a reason to put down a pet are those who have either: plenty of money to spare; no pets at all themselves (it's easy to judge others); the capacity to borrow lots of money or go into debt;good friends who can lend them money; a vet who will let them have accounts or willgive them cheap service and/or who have never had the misfortune of suddenly being asked to spend many thousands of dollars all at once on an acutely, severely ill or injured pet(e.g. dogs with spinal fractures or bloat). Many people of this view believe that a life is a life and that we humans have no right to take a life, particularly if theonly factor is money. Some of these people also believe that vet clinics shouldnot charge for their services (so that more animals will survive) and that if you, the owner, can not afford to pay for a pet's emergencies then you should not own a pet.

The people who think that financial reasons are a valid reason for euthanasia:

Pet ownership is a concept that is held dear by most Westernised countries and, increasingly,by many Eastern countries. It is commonly believed and the opinion perpetuated by the pet industry(those guys who want to sell you pet food and dog toys and vet services ...) that all people should have the right to an animal companion and that it should not be a matter of money and financial capabilities to own an animal because of all of the supposed health benefits that animal companionship brings to the person: improved exercise, improved mental health, companionship, depression relief and so on. The unfortunate side effect of this 'everyone deserves a pet'attitude is that sometimes the unfortunate pet gets put down for very treatable diseases simply because the owner can not afford the costs of therapy. This outcome isconsidered by people of this opinion to be an acceptable, although sad, outcome, however, because of the joy the pet brought to the owner whilst it existed. Many of this view also believe thatvet clinics should not charge for their services because, although they will put downtheir pet rather than pay money for it, they really would like to have their pet treated for free if they can and have their cake and eat it too.

From a veterinary perspective, it must be stated that most of us are generally in support of the concept of financial euthanasia (after all, if we weren't, we would never perform the procedure for financial reasons and all of our services wouldbe free to non-financial people). To say we facilitate and support it is not tosay, however, that we enjoy the practise. Vets hate putting down animals for financial reasons, however, vets also run businesses that are competitive and cost a fortune to operate. Our only choice, then, when confronted with totally non-financial owners and very ill pets, is to go out of business treating people for free or to 'cure' an animal's suffering or disease through humane euthanasia. We don't want to go out of business and so we choose the latter: this is why financial euthanasia becomes an option for vets. Most vets would prefer that people who can not afford basic care for their animals not have animals and then they wouldn't have to kill so many pets.

Author's opinion: My personal opinion on the matter of financial euthanasia(before you get offended, remember that this is only one opinion) is that the best choice probably lies somewhere in the middle of these two extremes and is greatly dependent on owner situation and medical situation. I do not personally believe that every person, regardless of their financial situation, should be allowed to own an animal. If your finances are so drastic that you can not afford to provide a pet with basic standards of husbandry,living and basic medical care (e.g. proper nutrition, comfort, a clean environment,basic vaccinations, desexing, worming, dental care, treatment of minor emergencies or healthissues etc.), then I do believe that you should probably think twice before taking on the responsibility of caring for a pet's life. After all, such a pet is almost guaranteed to be surrendered or euthanased the moment something moderately medical or surgical goes wrong with it and these owners are often fully aware of this likelihood when they take on the pet in the first place. Vets and charities should not be relied upon to foot the bill of irresponsible ownership decisions. I do, however, believe that reasonable financial limitations can be valid grounds for pet euthanasia, particularly in the case of high-cost, suddenly-occurring ailments (e.g. emergency cases where no saving-up can be done) where the expenditure of limited financial reserves can not even be met with anyguarantee that there will be a live pet at the end of the day or in cases when theowner's financial situation (e.g. housing changes, financial crises, a new baby) has recentlychanged, making a financial situation into a non-financial situation through no faultof bad planning or irresponsible pet choices.

Additional note: To make a point about the unlimited finances situationthat some of the well-off have, it is also my opinion that infinite financial resources shouldnot be a reason to keep on treating a poor animal for a terminal illness or incurable diseasewhen euthanasia is a readily accessible option for ending a poor pet's suffering. Manypets with terminal illness are forced to survive way beyond what is humane by rich,overly-cashed-up owners who just won't let go.

The owner is moving house or changing situation and owns apet that can not cope with the stress of moving or rehoming:

Some pets are so anxious about minor changes in their lives that they are unable to be rehomedor relocated at all without this setting off a major crisis. Some animals will develop andexhibit severe anxiety behaviours: self-mutilation, psychosomatic vomiting and diarrhoea, pacing, stereotypic behaviours, overgrooming etc. and others will develop stress-induced diseases: e.g. feline idiopathic cystitis (FIC), urethral obstruction in cats (iFLUTD - idiopathic feline lower urinary tract disease), Addison's disease, colitis, feline herpesvirus signs (cat flu) and herpes ulcers of the cornea. Often these animals will not be able to be rehomed by the owner or by a shelter because of the stress tothe animal and the fact that most prospective owners do not want to take on an animal with behavioural problems. For these animals, euthanasia may be the most humane option for the animal.

The animal is in a shelter and has a behavioural or medical reason as to why it can not be rehomed:

Even though shelters do try to save and rehome every animal where they can, a responsibleshelter will not attempt to rehome a pet with a major behavioural or medicalproblem. Doing so just results in that pet being surrendered over and over again andeven being subjected to cruel punishments from their new owners. In addition, the rehoming of aggressive or unpredictable animals may result in injury to the new owner orthe owner's other pets.

2b) Not so valid reasons for putting an animal down.

The following is a list of reasons that I consider to be not so valid reasons for havinga dog or cat or other animal euthanased. Note that I have not used the term "invalid" herebecause there will always be individual situations whereby one or more of these reasons for euthanasing an animal are completely valid and reasonable (except the last twoon the list). Please note that this is not an exhaustive list: people think of manystupid reasons for putting their pets down.

The pet has outlived its usefulness and the owner just does not want it around anymore - the pet is no longer young, cute, trendy, interesting, able to produce pups for sale, able to win in the show ring, able to win races ... and so on:

Unfortunately for pets and for the shelters that have to constantly rehome unwanted anddumped animals, pets are all too often becoming the silent victims of a "trend" or "fad" society. These animals are not seen as individual living creatures with valuable lives of their own, but as thingsto discard when we no longer need or want them or when the next fad comes along.People want to be like Paris Hilton (2007-2008) and own a "tea-cup" or toy dog breed that can be carried around in a glamorous bag. Unfortunately, these animalsalso crap, vomit and wee in the designer bag, which is not so glamorous, and they do get old and less-cute and suffer from medical issues and ... worst of all ... they do go out of fashion. Killing a healthy pet simply because it is no longer cute, pretty, fun,fashionable or useful to you is not acceptable, in my opinion. If you are unwilling to commit to caring for a pet's life for the long term (up to about 12 years for thedog and 16 years for the cat) or beyond the time that the animal is in fashion or useful, then you should probably not take on the responsibility of a pet. Get a designer dress instead. If you already have such an animal and you are contemplating putting it down, I would urge you to rethink this course of action. If the unwanted animal is healthy and has none or only minor behavioural defects, then these unwanted animals can often be surrendered to a shelter and rehomed(and, yes, some people do want adult dogs and cats and even old animals to own and love).

Unfortunately for pets and for the shelters that have to constantly rehome unwanted anddumped animals, pets are all too often becoming the silent victims of a "trend" or "fad" society. These animals are not seen as individual living creatures with valuable lives of their own, but as thingsto discard when we no longer need or want them or when the next fad comes along.People want to be like Paris Hilton (2007-2008) and own a "tea-cup" or toy dog breed that can be carried around in a glamorous bag. Unfortunately, these animalsalso crap, vomit and wee in the designer bag, which is not so glamorous, and they do get old and less-cute and suffer from medical issues and ... worst of all ... they do go out of fashion. Killing a healthy pet simply because it is no longer cute, pretty, fun,fashionable or useful to you is not acceptable, in my opinion. If you are unwilling to commit to caring for a pet's life for the long term (up to about 12 years for thedog and 16 years for the cat) or beyond the time that the animal is in fashion or useful, then you should probably not take on the responsibility of a pet. Get a designer dress instead. If you already have such an animal and you are contemplating putting it down, I would urge you to rethink this course of action. If the unwanted animal is healthy and has none or only minor behavioural defects, then these unwanted animals can often be surrendered to a shelter and rehomed(and, yes, some people do want adult dogs and cats and even old animals to own and love).

The owner is relocating to a place where pets are not permitted or practical:

Life circumstances change and sometimes a good pet is not longer able to remainwith an owner. This is not always anyone's fault: people lose jobs, lose their homes, increasetheir work hours, are forced to go into pet-free rentals, get positions overseas and so on. These pets that can't be kept should not be automatically put down, however. Attempts should be made to rehome these animals or at least place them in a rehoming shelter before euthanasia is elected.

The owner's living circumstances have changed (e.g. a newbaby is joining the family, the owner has no time for an animal) and the pet is not able to be part of that new living arrangement:

This is similar to the example given above. Life circumstances change. Attempts should be made to rehome these animals or place them in a rehoming shelter before euthanasia is elected.

The animal has behavioural issues that the owner does notwant to take time and effort to correct:

Many busy owners think that pets should train themselves. They see the perfect dogs andcats on TV, the movies and in the street and think that such good behavior happens by magic.The truth is, it happens with a lot of training, time, pet education classes and hard work.When the untrained pet suddenly grows up and starts becoming aggressive and pushyat home; tears the place down when the owner leaves the house; starts attackingother pets; won't toilet outside or starts barking and annoying the neighbors, many peoplesee euthanasia of that problem animal as a quick fix: problem solved. This is not acceptable. Pets can be euthanased for behavioural issues (as mentioned in section 2a), however, this should not take place until everything has been tried that should be tried: dogclasses, veterinary consultation, consultation and assistance by a veterinarybehaviouralist.

Author's note: One exception to this point is aggression towards people. Some dogs and cats, especially large breed dogs, can be so aggressive as to pose a significantsafety risk to their owners, the public and other pets. These animals may be candidates for euthanasia with minimal intervention because of the risk of a major attack incident taking place whilst behavioural modification is taking place.

It is cheaper to euthanase a 'cheap' pet and get a new one than itis to treat any minor to moderate illness it might have:

This is the not-so-valid amendment to the issue of financial euthanasia that I mentionedpreviously in the first paragraph of the financial euthanasia point in subsection 2a.It is probably the major reason why "cheap to buy" pet fish, birds and rodents are euthanased and,in my opinion, it is disgusting. To sum up the attitude held by these owners: "it only cost me five dollars to buy the fish so why should I see a vet and spend fifty, eighty dollars to treat its illness?" Why? Because, in my opinion, when you purchased that 'cheap pet', you made a moral contract with that animal life that you would care for it and be its advocate and guardian. A life is a life: these creatures are not just things. It matters to that bird or fish or rodent that you care about it. After all, like yourselves, these animals only get one shot on this earth. If you are not going to be willing to look after your pet, whatever the (reasonable) costsof caring for it are, please don't buy a pet.

Author's note - as discussed in section 2a, if the animal is going to cost many hundreds or thousands of dollars to fix (money you don't have) or if the animal has a very low chance of survival regardless of money spent, then financialreasons may be quite appropriate reasons for the euthanasia of these animals. The point I ammaking in this section is that these small pets (fish, birds, rodents, reptiles) should just not be seen as cheap, throw-away, flush-down-the-toilet pets.

Custody disputes:

In recent years, bitter custody battles have started to crop up whereby ex-partners(married or otherwise), lawyers in tow, are fighting over which of them gets full custodyof the family pet. Unfortunately, one of the side effects of all this pain and angstand high-feeling is that, every now and then, one of the two owners will attempt to get some formof revenge on the other person by euthanasing the pet in question. It's one of those "ifI can't have it, then no-one will" situations. Don't do this. It's not the pet's faultthat your relationship fell apart so don't punish the animal.

Putting down this pet and getting a new one next year is cheaper than paying to board the petover the Christmas and summer holidays.

I put this one in because I have personally seen it. Most reasonable people would (and should) be aghastat this: it is a completely abhorrent reason for euthanasia of an animal. I once knew of a family who put down their dog each year when they went away because a new puppy was cheaper to buy than paying a few month's worth of boarding kennel fees was. Sometimes you wonderabout people.

3) How do you decide when it is time to euthanase a pet?:

One of the most common questions that I am asked as a veterinarian is the "how will Iknow when it is time to put him/her down?" question. The honest truth is that is no easy way to answer this question: it depends on the individual owner, the individual animal, the individualcase (e.g. the type of medical problem, behavioural issue) and a fair bit of emotion and "gut-feeling"by both owner and vet. I have attempted to give you some assistance on this matter by providingyou with some tips on how you might come to recognise "the time" (3a) and also some hints on how to recognise that an animal is "in pain" (3b). Most owners do not want to see their beloved friend in pain and will often see uncontrollable, unremitting pain as a signal that the time has come to say goodbye: this section (3b) should aid you in identifying it.

3a) How will I know when it is time to euthanase my pet? - hints and tips on how to know when the time has come to have your dog or cat or animal friend put down.

You have started asking the question:

In my experience, once owners start asking themselves and their veterinarian the question:"do you think it is time to put him or her down?", they have already well and truly advanced in the decision making process. People tend to get a gut feeling about when it is time. They just know in their heart that things are not right with their pet's spiritand that things are unlikely to improve: their animal is depressed all the time,it seems sad and/or in constant pain, its weight is dropping, it doesn't enjoy eating anymore, it doesn't respond to them like before and so on.

Have a family discussion about it:

Every member of the family will be feeling the effect and heart-ache of their pet's deterioration. Talk about it. Everyone will have their views and someone may make a valid point that no-one else has thought of that sways the decision one way or the other.Involve your children in this decision if you consider them emotionally mature enoughto face this reality.

Have a discussion with your vet (ask a couple of veterinarians if you need to):

Veterinarians see a lot of pets in their careers and often need to counsel pet owners about euthanasia. Veterinarians can often provide you with informed, objective informationand advice on what degree of suffering and/or pain your pet is in or expected to be in with regard to the type of condition it has. This advice can often be very useful in the decision-making process because it comes from an informed, experienced, professional sourceand is not being clouded by the same degree of grief and emotion that you, the pet's owner, are experiencing. Your vet can also provide you with extra pain killers (analgesics) and advice on ways to make your pet comfortable, should you require a day or so at home with your petto say goodbye.

Keep a pet diary:

I have found that keeping a diary helps a lot of owners to gauge when the time has cometo say goodbye, particularly in those cases where the pet has a slow-moving, chronic, progressivedisease (e.g. heart failure, renal failure, arthritis, cancer). The pet diary is basically a day-to-day record ofhow the pet feels, behaves and acts. You can put whatever you like in the pet diary, however, I have found that many owners find it helpful to note such useful indicators of health and well-being as:

- Responsiveness to you: does your pet respond when called?; respond to being petted? etc.

- Ability to walk: e.g. the pet walks well; walks a few steps but tires easily; can not get up at all and so on.

- How much the pet ate today: e.g. calories eaten each day, volume of food eaten and so on.

- How keen the pet is to eat: e.g. does it gobble its food?; pick at the food?; refuse to eat? etc.

- How much the pet is drinking: you can measure how much the pet is drinking each 24 hours.

- Whether the pet is urinating: you can note how often you see the pet wee each day.

- Whether the pet is defecating and if feces are normal: note how often you see the pet passing faeces each day and what the droppings look like etc.

- The pet's weight: weigh the pet daily or weekly - is the pet losing weight over time? Weight is a big indicator of health.

- Episodes of pain: e.g. crying when being handled, panting all the time, displaying aggression and so on (section 3b).

- Episodes of hospitalisation and duration of hospitalisation.

- Resting respiratory rate: each evening, when the animal is at rest, record the number of breaths it does per minute.

- Disease signs and if the worsening or improving: e.g. for heart failure, you could note if the pet is coughing more than normal (e.g. coughs seen per day); for arthritis you could note the degree of lameness and time taken to "warm out of it."

What you want to establish is a way of objectively determining if the pet is getting worse or not. Thiscan be done by establishing a grading system of severity for each criteria (e.g. grade1-5) and noting the grade each day to see if it increases. For example, for thecriterion:

Can the pet walk, Grade 1 would be: gets to feet and walks well with no issues or tiring;Grade 2 would be: has some trouble getting to feet, but can walk well with minimalfatigue; Grade 3 might be: having significant trouble getting to feet and can only walkor stand for limited period of time before lying down again; Grade 4 might be: tries hardto get to feet but can not (needs help to stand, but can remain standing and even walk a bit once up) and Grade 5 might be: remains laying down and does not attempt to get to feet (flopsdown immediately when helped to stand). If, over time, you see the gradings for each of the individualcriteria increasing in severity (e.g. all 4s and 5s), then this can be an objective indicatorof when the time is drawing nearer.

Author's note: when looking at specific disease symptoms (e.g. coughing, diarrhoea) tosee if these are becoming worse over time, it is useful to find a way to grade these or number theseas described above so they can be objectively tracked over time. For example, writing down in the diary that the heart failure pet was "coughing today" is not going to be as usefulto you over time as writing down something more specific like "had three coughs today" or"coughing bout lasted for 30 seconds". Later on, you might find that you are writingdown "had twenty coughs today" or "coughing bout lasted 5 minutes", both of whichmight then indicate objectively that the pet is getting worse.

As a bare minimum, writing down in the diary whether you feel your pet "had a goodday today" or a "bad day today", according to your criteria of what a good day or badday is, can be very helpful. When you start to find that your pet's bad days are well exceedingits good days, then you know that the time to seek further treatment/advice or put thepet down is drawing near.

Your pet is now spending more time in hospital than it is at home:The significance of this obviously depends on the disease or condition the animal has. There are many curable diseases (albeit severe ones) that require a pet to spend a lot of time in hospital or going back and forth from hospital (e.g. certain surgical conditions that might require frequent follow-ups or follow-up procedures).This point is directed more towards those of you who have pets with chronic and/or terminalillnesses (e.g. advanced heart failure, renal failure, severe chronic pancreatitis, cancer). These pets often get to the end stage of their disease whereby they are so ill (all the time) thatthey keep on having to be admitted for hospital stays (often on a weekly basis or sooner) in orderto receive fluids, treat vomiting or diarrhoea, manage pneumonia, manage pain, manage congestive heart failure symptoms and so on. Eventually these sick pets are staying in hospital more than they are staying at home and this is stressful and really no life for a much loved pet. It is terribly emotional and distressing for the owners of thepet too, not to have them at home.

The pet has a terminal illness and is admitted to the vet clinic because of acute, emergency deterioration: It is not uncommon for pets with severe, chronic and/or terminal illnesses to experiencean acute episode of disease-related deterioration necessitating a rapid trip to the nearestemergency centre or vet clinic. For example: animals with internal cancers often presentto veterinary clinics in states of severe shock and collapse after having hemorrhaged severely fromtheir large tumors; animals with congestive heart failure often present to emergencycenters with signs of severe pulmonary edema (fluid on the lungs) and distressed breathing; animals with renal failure may present with severe vomiting of blood and shock; cats with hyperthyroidism or cardiac disease may present with acute thromboembolism or FATE(blood clots entering the hind legs or lungs and causing, respectively, sudden paralysis andpain in the hindlegs or acute respiratory distress). When confronted with the acute, severe deterioration of a pet's terminal condition, it is often kinder for owners to let these pets go (put them down) rather than working on them intensivelyand putting them through aggressive medical treatment just to revive them and bring them back for the very short term.

The pet has no quality of life: Quality of life is a subjective, tricky term that can apply to many facets of a pet's lifenot just its physical health. It also applies to the pet's mental health as well. An animal that is sick all the time, barely eats any food, is losing weight severely, is in constant pain, can't get to its feet and so on can easily be described as havinga poor quality of life. Likewise, an animal that is in constant mental anguish(e.g. an animal that is suffering from severe, unmanageable separation anxiety or that is not coping at all well with blindness) may also be considered to have a poor quality of life.

You are starting to feel that you are keeping the pet alivebecause you can't say goodbye not because the pet has quality of life: Don't feel ashamed or guilty if you are in this position. It is probably the most common reasonwhy pets that should be euthanased are not. Pets are important members of the family,in many cases taking up a big portion of our own lives (a cat that lives to 25 has beenwith its owner a third of that owner's life or more). We come to rely on their sure presenceas much as on the presence of any human member of the family. We need them. It is hard to say goodbye. At the same time, an owner's inability to let go should not be a reason why a sufferingpet is made to go on living. Once you have come to the realisation that you arekeeping your pet alive because you can't live without it, it is time to let go. Putting down a pet is hard, but it is also an act of extreme self-sacrifice and mercy.You wouldn't want a loved family member to suffer.

3b) How to recognise that a pet is in pain.

One of the major criteria that veterinarians use to determine whether an animalis suffering or not is the presence of constant pain. It is also the main criteria thatowners use and ask their vet about when trying to decide when to put a pet down. An animal might be deemed to have an acceptable quality of life if it can not move around much; coughs occasionally or has a large mass on its face so long as it is pain-free,however, the presence of unmanageable moderate to severe pain is not acceptable and is not considered conducive to a good quality of life even if the animal is otherwise surviving okay. In order to determine whether an animal is in pain or not, both owners and their vets need to be able to recognise the signs of pain and discomfort. Unlike human patients, animals can not tell us in words how much and where something hurts.

Symptoms of pain in animals:

- Whining, whimpering, vocalising (i.e. crying out in pain) or groaning/moaning.

- The animal cries out in pain or yelps when it tries to move.

- The animal cries out in pain or yelps when it is touched or handled, particularly if the painful region of the body is touched.

- The animal seems depressed and subdued compared to normal.

- The animal keeps to itself, seeks isolation away from the family or herd.

- The animal chooses to hide itself (e.g. hiding under the bed, in corners, dark places).

- The animal is reluctant to move from a comfortable position.

- The animal is restless: sometimes, rather than hiding or staying still, a painful animal will be unable to settle and will pace the room or yard.

- The animal remains standing and won't sit or lie down.

- The animal is unable to sleep.

- The animal goes off its food (stops eating or becomes very picky with its food).

- The animal has an elevated heart rate: animals in moderate to severe pain will usually have a higher than normal heart rate.

- The animal has an elevated temperature: animals in moderate to severe pain will usually have a greater than normal temperature.

- The animal is panting excessively: dogs in particular pant when in significant pain.

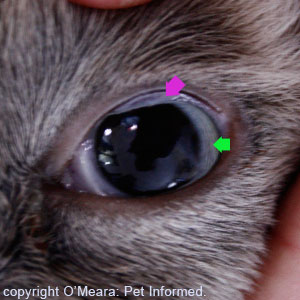

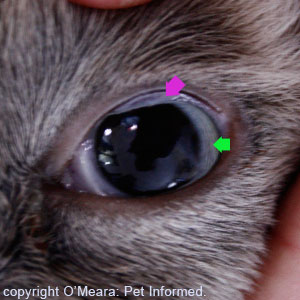

- The animal's pupils are dilated. Some animals are good at masking symptoms of pain and all you may see are widely dilated pupils.

- An otherwise nice-mannered animal exhibits aggression (biting, snapping, growling) when touched or approached.

- The animal bites or licks at the painful region of the body (e.g. animals with arthritic joints will often lick the skin over the painful joint).

- The animal self-traumatises: animals with severe pain can attack the painful region of the body. Birds will sometimes pluck out feathers in painful regions. Mammals will often pluck out fur. Some traumatize themselves so badly that they put holes in their own flesh.

- The animal limps or walks stiffly: animals with painful joints and limbs will often limp as a sign of pain. Note that limping is not always a pain sign: e.g. animals with non-painful scarred or fused joints may have a reduced range of motion in the affected limb which can make them move oddly and appear to be limping.

- The animal grinds its teeth: livestock animals and horses in particular will grind their teeth when in pain. Dogs and cats and rodent and rabbit pets will also do it.

- The animal is drooling: drooling can be a sign of pain in some pets.

- The animal is squinting: animals with eye pain and head pain (e.g. head ache) will often squint one or both eyes.

- The animal 'chatters' its teeth: animals with mouth pain and dental pain will sometimes chatter the teeth, especially when eating or drinking.

- The animal has a lesion/problem that is expected to be painful. Even if the animal shows minimal symptoms of pain, you can assume that an animal is in pain if it has certain "painful" problems (e.g. fractured limbs, kidney stones, gall stones, intestinal blockages).

3c) I just want to let my pet die at home - is this okay?

As a veterinarian, this is a very common question that I am often asked by ownersof chronically ill or terminally ill pets. These are usually owners who can not quitebring themselves to make that final decision: they hold off on the active euthanasia of a critically ill pet in the hope that the pet will just "die in its sleep."

The sad truth of the matter is that many (maybe most) of these left-to-die pets do die in their owner's sleep (they are found dead when the owner gets up in the morning), but they do not die in theirs. Death is unfortunately not always a swift or painless processthat occurs whilst you are sleeping. Some forms of death can be very painful or highly distressing (e.g. heart failure, respiratory failure) and many occur over several hours, not mere minutes (much slower than you as a loving owner would like to think happens). For this reason: the prolonged suffering that may occur as the animal is dying, I am not in favour of letting pets die at home. Not when assisted euthanasia is available and is so quick and peaceful and painless.

3d) I just want a few more days with my pet at home before putting him or her down - what are my options?

Whether this is a viable or humane option and whether there are ways of relievingyour pet's distress or pain during this at-home period depends on the disease process affecting the animal.

With some diseases or conditions, particularly those where the pet is suffering a lotof distress or discomfort despite intensive veterinary care (e.g. animals with severe sepsis or severe heart failure or a twisted bowel) and/or the animal needs significantintensive care and supportive medications just to stay alive, sending the pet home with the owner for a few days is not recommended for humane reasons. The animal is likely to suffer, the family is likely to suffer emotionally seeing their pet in distress and painand it is very likely that the pet will die horribly at home. In these cases, it is kinderto say your goodbyes and spend time with your pet in the vet clinic before having the petput down.

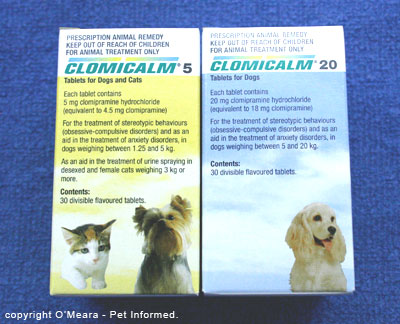

With other conditions such as painful cancers or severe arthritic conditions, where the petis in pain but not actively dying and euthanasia is more elective than imminently urgent, you do have the option of taking your pet home and spoiling it for a few days beforehaving it put down. Your vet can supply you with really good pain relievers to ease yourpet's discomfort. These analgesics include non-steroidal drugs (e.g. carprofen, meloxicam, firocoxib,aspirin) and, for severe pain, opiate drugs such as tramadol, morphine or codeine tablets, buprenorphine oral liquid or fentanyl slow-release patches (these patches are brilliant andrelease fentanyl into the animal's body through the skin over three days). Your pet can also be given sedative drugs(e.g. diazepam, xanax or acepromazine tablets) to relieve any distress.

Author's note: always be aware that any terminally ill pet may suddenly deteriorateand/or die at home even if this is not expected by the veterinarian to occur soon. Animals with any severe disease can suffer sudden heart arrhythmias; tumours can suddenly hemorrhage; animals can throw blood clots into their lungs and so on: all of which can result in thesudden deterioration and/or death of the at-home patient. Be aware that, should you choose to have a very sick pet at home with you for a few days, you could wake up or come home to a deceased pet or witness your pet's sudden deterioration and death.

3e) Why won't my veterinarian just tell me when to put down my pet?

Owners of chronically ill or terminally ill pets seeking definitive advice often ask their veterinarian such questions as: "What would you do if s/he was your pet?,""What do you think I should do?" and "Do you think it's time?" Although someveterinarians will give a direct answer when asked such a question, it is more common forveterinarians to avoid giving the owner a definite answer on the matter of euthanasia, which can often be frustrating to the client.

There are several reasons why veterinarians often refuse to tell clients outright when to euthanase their pet. Many feel that the decision to euthanase is not a decision that the vet can make, but a private, personal, emotional decision which the owner alone must make for his or her peace of mind. Many vets are also afraid of telling an owner to euthanase for fear that an emotionally unready owner will takeoffense and be angry at the vet for "pushing them" to make the decision. In additionto this, many vets are concerned about the possibility of an owner coming backto them after the euthanasia, having read or heard about other options for their pet's treatment, feasible or not, angry that their vet told them to euthanase.

4) The euthanasia process itself:

The following section contains all of the information you, as an owner, need to knowabout the process of euthanasia in animals. Although mention will be made of alternativemethods of euthanasia (e.g. captive bolt euthanasia, decapitation, gassing) where appropriate, the focus of this section will be on the use of injectable euthanasia drugs (e.g. pentobarbitone) because these are the agents most commonly used for the humane euthanasia of domestic pets.

4a) What euthanasia methods are available to vets for the putting down of domestic animals?

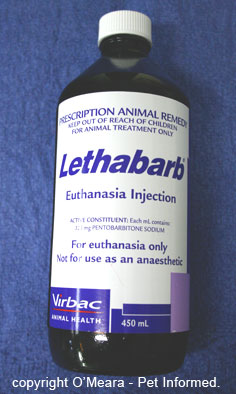

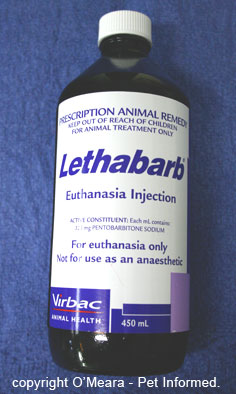

Injection of a barbiturate drug (pentobarbitone sodium):

The most common method by which animals (particularly small pet animals and horses) are put to sleep is through the use of an intravenously-given, injectable barbiturate drug called pentobarbitone, also referred to by trade names such as Valabarb, Pentobarb and Lethabarb. Most commercial preparationsof pentobarbitone euthanasia solution come mixed with a green dye for ease of identification. Pentobarbitone is very closely related to some of the drugs that vets use to induce general anaesthesia in animals. During the process ofeuthanasia, this chemical essentially acts like a severe overdose of veterinary anaesthetic: it enters the animal's blood stream and suppresses the function of the animal's heart and brain, causing instant loss of consciousness and pain sensation and stopping the beating of the animal's heart, thereby causing death whilst the animal is deeply asleep. This is where the term "put to sleep" comes from. The animal peacefully and instantly falls asleep (undergoes anaesthesia) and then passesinto death without any pain.

The most common method by which animals (particularly small pet animals and horses) are put to sleep is through the use of an intravenously-given, injectable barbiturate drug called pentobarbitone, also referred to by trade names such as Valabarb, Pentobarb and Lethabarb. Most commercial preparationsof pentobarbitone euthanasia solution come mixed with a green dye for ease of identification. Pentobarbitone is very closely related to some of the drugs that vets use to induce general anaesthesia in animals. During the process ofeuthanasia, this chemical essentially acts like a severe overdose of veterinary anaesthetic: it enters the animal's blood stream and suppresses the function of the animal's heart and brain, causing instant loss of consciousness and pain sensation and stopping the beating of the animal's heart, thereby causing death whilst the animal is deeply asleep. This is where the term "put to sleep" comes from. The animal peacefully and instantly falls asleep (undergoes anaesthesia) and then passesinto death without any pain.

Occasionally, the veterinarian will not be able to inject the drug intravenously into one ofthe animal's peripheral (limb or leg) veins: the usual site of euthanasia solution administration. This can be for many reasons: the animal is in such severe shock that the leg veins are too collapsed and small to access; the animal is too aggressive to permit the vet safeaccess to a vein or the animal is far too small (e.g. mice, rats, birds) for a vein to be entered. In these cases, the euthanasia drug may be administered by direct injection of thedrug into the animal's heart or by injection into highly-vascular (blood vessel rich) organs such as the liver or kidney (the blood vessels absorb the drug and death is rapid). The drug is highly absorbed through most routes of administration and can even be given orally to animals to induce death(this route is sometimes used in birds and small rodents, rarely with larger animals because it isslower to induce death than direct injection and large volumes are needed).

Intravenous injection of potassium chloride:

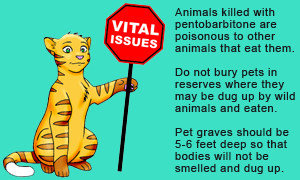

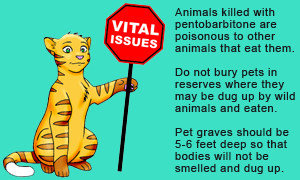

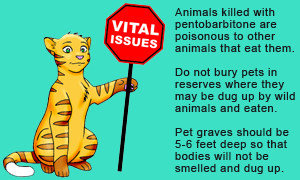

Occasionally, euthanasia may be performed on an animal via the administration of large volumesof potassium chloride: this causes the animal's blood potassium levels to rise to critical levels, resulting in the animal dying from heart arrhythmia (sort of like a fatal, severe heart palpitation in people). Because potassium chloride injection is thought to be painful, the animal is normally placed under general anaesthesia before the potassium solution is injected. Potassium chloride injection is not a method that isgenerally used in routine pet euthanasia; it is typically used in the euthanasia of horses whereby there is the possibility for the horse's meat to enter the food chain (meat that contains barbiturates is lethal to other animals that eat it).

Captive bolt euthanasia:

A captive bolt pistol is a special gun that fires out a steel bar (a bolt) at high speedand force instead of a bullet. It is sometimes used in the euthanasia of horses and other livestockanimal species. The pistol is placed against theanimal's skull and the bolt is fired into the animal's brain, causing catastrophic braininjury and instant death. It sounds horrible, but provided that the person performingthe euthanasia is experienced and knows exactly where to place the pistol in order to hit the rightsection of brain, captive bolting is extremely quick and humane.

Pistol or gunshot euthanasia:

This is similar to captive bolt euthanasia except that the pistol or rifle used fires out a bulletat high speed instead of a bolt. Shooting is commonly used in the euthanasia of horses, livestockand wildlife animal species (e.g. kangaroos) in remote farmland properties. The gun is placed against theanimal's skull (or aimed at the head in the case of wildlife) and the bullet is fired into the animal's brain, causing catastrophic brain injury and instant death. It sounds horrible, but provided that the person performingthe euthanasia is experienced and knows exactly where to place or aim the pistol/rifle in order to hit the rightsection of brain, shooting is extremely quick and humane. The shooter must have a firearmslicence and there are rules about where shots can be fired and who can be nearby because of the risk of wayward bullets hurting the public.

Gassing:

Toxic gases such as carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide are rarely used in the euthanasia ofpet animals. They are sometimes used to kill poultry and pigs for human consumption although, technically,this should be termed slaughter rather than euthanasia. Gassing (especiallycarbon monoxide) is also considered to be an acceptable means of euthanasing pest bird species such as Indian Mynas.

Electrocution:

Electrocution is not generally used in the euthanasia of pet animals except in cruel and illegal situations (e.g. a 2008 Four Corners documentary on illegal dog fighting in the UK showed images of a pitbull terrier being put down using electrocution). Electrocution is sometimes used to kill poultry and rabbits for human consumption although, once again, this should technically be termed slaughter rather than euthanasia. Electrocution is considered to be an acceptable means of euthanasing pest rodent species such as miceand rats and there are commercially available devices designed to do just that.

Decapitation (beheading):

Decapitation is the technical term for chopping off the head (of an animal or person).Decapitation is not generally used in the euthanasia of pet animals except, on rare occasions,in the euthanasia of pet and commercially-grown fish. Decapitation is sometimes used to kill poultry and fish for human consumption, although thisshould technically be termed slaughter rather than euthanasia.

Cervical dislocation (breaking the neck):

Cervical dislocation is the technical term for breaking the neck of an animal or human.This method is not generally used in the euthanasia of pet animals except, on rare occasions,in the euthanasia of pet mice, rats, birds and rabbits. Although it sounds terrible, when performedby an experienced operator, cervical dislocation is an exceptionally swift, humane meansof putting an animal down. It must only be performed by an experienced operator however. Cervical dislocation is sometimes used to kill poultry, rabbits and other birds for human consumption, however this should technically be termed slaughter rather than euthanasia. It is considered an acceptable means for killing pest birds (pigeons etc.) and rodents andis one of the main methods by which laboratory mice and rats are euthanased for tissue studiesand post mortem.

Exsanguination (blood letting):

Exsanguination is the technical term for bleeding an animal out (draining it of blood): this is normally achieved by cutting the throat of the animal in question. Exsanguination is not used in the euthanasia of pet animals because it is too distressing to watch. It is a technique that is sometimes used to kill poultry, rabbits and livestock animals (e.g. sheep and goats) for human consumption, although this should technically be termed slaughter rather than euthanasia. Compared to the other methods discussed above, blood letting is a relatively slow and painful process and is not recommended for the humane euthanasia of pet animals.

4b) How is euthanasia solution given to pets? - this section contains detailed, specificinformation on the humane euthanasia of dogs, cats, mice, rats, guinea pigs, rabbits, birds, ferrets,reptiles, fish, horses and livestock animals.

As mentioned in the previous section, the main method by which veterinarians humanelyeuthanase animals is through the administration of a barbiturate euthanasia drug calledpentobarbitone. As was also mentioned above (section 4a), this drug is able to be absorbedinto the animal's bloodstream via almost any route of administration. It is typically given intravenously(by direct injection into the animal bloodstream), but can also be given by intracardiac injection (needle into the heart), injection into the liver or kidneys, intraperitoneal injection (into the abdominal cavity)or even orally. Intravenous, intracardiac and liver or kidney administration will generallyresult in an extremely rapid (instant) loss of consciousness for the animal. Intraperitoneal andoral administration of the drug tends to result in a slower death, a gradual drifting off to sleepover a few minutes, because the drug takes slightly longer to absorb into the blood from theselocations.

As mentioned in the previous section, the main method by which veterinarians humanelyeuthanase animals is through the administration of a barbiturate euthanasia drug calledpentobarbitone. As was also mentioned above (section 4a), this drug is able to be absorbedinto the animal's bloodstream via almost any route of administration. It is typically given intravenously(by direct injection into the animal bloodstream), but can also be given by intracardiac injection (needle into the heart), injection into the liver or kidneys, intraperitoneal injection (into the abdominal cavity)or even orally. Intravenous, intracardiac and liver or kidney administration will generallyresult in an extremely rapid (instant) loss of consciousness for the animal. Intraperitoneal andoral administration of the drug tends to result in a slower death, a gradual drifting off to sleepover a few minutes, because the drug takes slightly longer to absorb into the blood from theselocations.

The following points provide information on how I generally perform euthanasia onpet animals using the most humane techniques of barbiturate administration.

Canine Euthanasia (Euthanasia of dogs):

Most canines have readily accessible veins in their legs and most vets tend to give the pentobarbitoneinjection via these veins. If the animal is anxious or excitable, I tend to give the pet a sedativeinjection prior to euthanasia as a way of relaxing and settling the animal before putting it down. This sedation may not be required if the animal is very sick or depressed at presentation. Occasionally, dogs will be encountered that are in such severe shock that I can not get access to a peripheral (leg) vein. The barbiturateinjection will then need to be given into the dog's jugular (large neck vein), heart orabdominal cavity (the aim is to inject the pet's liver).

Feline Euthanasia (Euthanasia of cats):

Most felines have readily accessible veins in their legs and most vets tend to give the pentobarbitoneinjection via these veins. If the animal is anxious or excitable, I tend to give the pet a sedativeinjection prior to euthanasia as a way of relaxing and settling the animal before putting it down. This sedation may not be required if the animal is very sick or depressed at presentation. Occasionally, cats will be encountered that are in such severe shock that I can not get access to a peripheral (leg) vein. The barbiturateinjection will then need to be given into the cat's jugular (large neck vein), heart orabdominal cavity (the aim is to inject the pet's liver or kidney). Tiny kittens andsuper-aggressive cats will sometimes receive their injection into the heart or abdominalcavity because of the difficulty (or danger) of accessing leg veins. These animals will generally be heavily sedated prior to administration of the drug by this means.

Euthanasia of ferrets:

Although ferrets do have accessible veins in their legs, it can be very difficult forvets to access these veins in alert aggressive or wriggly ferrets. These animals will normallyrequire a sedative or gaseous anaesthetic before a leg vein or jugular vein is able to be accessedin them. If the animal is very depressed or sick at presentation, the animal may not resisthaving an injection in its arm at all, which will make it easier for the vet to administerthe barbiturate via this route. More typically, I find, ferrets tend to be euthanased by injection ofbarbiturate drugs directly into their hearts or abdominal cavities (the aim is to inject the pet's liver or kidney).Although this euthanasia procedure can be performed with the animal fully conscious (particularly in very sick, non-resistant animals), I tend to find it nicer for pet and owner if the animal isgassed down first (using anaesthetic gas, not poison gas like carbon monoxide or dioxide)to render it unconscious and pain free before the drug is injected into these locations.

Euthanasia of small rodents:

Most small rodents: rats, mice, gerbils, hamsters and guinea pigs (cavies), do not have readily accessible veins in their legs or necks. Their blood vessels are generally too smallfor the vet to administer barbiturate drugs via this route. Small rodents tend to be euthanased by injection of barbiturate drugs directly into their hearts or abdominal cavities (the aim is to inject the pet's liver or kidney). Although this euthanasia procedure can be performed with the animal fully conscious (particularly in very sick, non-resistant animals), I tend to find it nicer for pet and owner if the animal isgassed down first (using anaesthetic gas) to render it unconscious and pain free before the drug is injected into these locations.

Euthanasia of rabbits:

Most rabbits do have somewhat accessible veins in their legs and ears (they have a large ear vein that can receive a small needle) into which the Lethabarb can be injected. Highly resistant or aggressive animals will normally require sedation or gaseous anaesthesia before one of these veins is able to be accessed. If the animal is very depressed or sick at presentation, the animal may not resisthaving an injection placed into its arm or ear vein at all, which will make it easier for the vet to administer the drug via this route. More typically, I find, rabbits tend to be euthanased by injection of barbiturate drugs into their hearts or abdominal cavities (the aim is to inject the pet's liver or kidney). Although this euthanasia procedure can be performed with the animal fully conscious (particularly in very sick, non-resistant rabbits), I tend to find it nicer for pet and owner if the animal isgassed down first (using anaesthetic gas) to render it unconscious and pain free before the drug is injected into these locations.

Euthanasia of birds:

Although most birds, even small birds, do have accessible veins in their legs, wings and necks,their blood vessels are generally too small and fragile and the handling stress on the bird too great (fully aware, active birds become very stressed by firm handling and needle-sticks) for this to be considered a humane or practical route of euthanasia for a conscious animal. More typically, small birds tend to be euthanased via injection of the barbiturate drugs directly into their hearts or abdominal cavities (the aim is to inject the bird's liver). Although this euthanasia procedure can be performed with the animal fully conscious (particularly in very sick, non-resistant birds), I tend to find it nicer for pet and owner if the animal isgassed down first (using anaesthetic gas) to render it unconscious and pain free before the drug is injected into these locations. A gassed down, unconscious bird may alternatively be given a euthanasia injection into one of the peripheral wing or leg veins instead of into the abdominal cavity or heart.